I was thinking about the issue of time this past week, while doing what I call cross-reading: reading items online and pausing every few minutes to look something up on a web browser and then returning to the original reading. This is a high-stimulation way of reading, producing an ultrathin layer of information about many different things, but not the intense experience of being deeply immersed in a book or other demanding piece of reading, which takes real time, not just internet time, to absorb and digest.

Almost thirty years ago, Roger Ebert wrote an enthusiastic review of Woody Allen’s film Radio Days, set in a Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn in the 1940s. It began:

I can remember what happened to the Lone Ranger in 1949 better than I can remember what happened to me. His adventures struck deeply into my imagination in a way that my own did not, and as I write these words there is almost a physical intensity to my memories of listening to the radio. Television was never the same. Television shows happened in the TV set, but radio shows happened in my head.

It’s this “happening in my head” that seems to be declining, replaced by constant and superficial connectivity, on the one hand, and exacerbated sensitivity to real or imagined slights on the other. Though teaching my courses continues to interest me, I often doubt that they interest most of the undergraduate students who enroll in them. A few, yes, but most sit passively with little or nothing to say. When I first enter the room, they’re all sitting silently, absorbed in their iPhones. Some continue playing with their iPhones during class, as if they think I can’t tell from the movements of their fingers, even if I can’t see the device itself. And in the lobby of my building, I’ve noticed that almost all the students who come and go are on iPhones as they walk, alone but not alone. Constant, instant, communication has colonized their time and minds. Does this matter?

Related: Summer Reading for Freshmen, Unchallenging, Mediocre

Long experience has taught me that students often don’t do the assigned readings, or do only part of them, or in all likelihood read on-line summaries of novels (which can be very thorough and detailed, but also rapidly forgettable). What is the difference between reading something at length and giving it a quick once-over?

There are two main ones: time and imagination. Two very dissimilar things: imagination, as Ebert noted, is internal. Time is external, and there are only 24 hours of it in a day. It takes perhaps 8 or 10 hours to read a 250 or 300-page novel. I know because I once spent a month at the British Library reading dozens of obscure dystopian novels that weren’t available in this country (this was long before the Internet, of course).

I used to reread each of the novels I taught in class, but this became discouraging: my knowledge and understanding of the works increased with each reading, while my students’ reading habits were moving in the other direction, spending ever less time on assignments. Like other professors, I’ve adapted to this reality to a large extent – using more short stories and essays, and feature films, in my courses. When I started teaching utopian and dystopian literature decades ago, I would typically include eight or nine novels in one semester. But then the semesters grew shorter (they are now at 13 weeks each at my university), and the habit of reading rarer.

Related: What Should Kids Be Reading

Years ago, some of my students told me that even between their experience and that of their younger siblings, there was an enormous gap: the younger kids were less likely to be interested in reading, whereas many of my students, in those days before the Internet, still loved books. These shifts are not due entirely to technology, though it plays a large role, and text messaging certainly made this problem worse, as everyone knows. The inevitable result is that more and more communication is going on about less and less: sheer trivia constantly conveyed to all one’s “friends.” Time is at a premium, apparently, and patience is short.

Universities have made many accommodations to this, as well. Not that long ago I served on a committee dealing with a proposal to change many three-credit General Education courses to four credits. The problem was how to do this without increasing the professors’ workload or contact hours, guarded by the contracts our faculty union negotiates with the administration.

A lengthy discussion ensued about what that extra one credit might entail: additional work for the students, yes, but without correspondingly increasing the professors’ work time. All kinds of ideas were floated. At one point I asked: “How about actually requiring the students to do all the work that’s already on our syllabus?” No one was amused. We pretended that the additional credit meant students would intensify and deepen their studies.

Since then, what we expect of our students has only decreased, even as many three-credit courses have indeed been transformed into four-credit ones, so that fewer courses are necessary to complete a bachelor’s degree. And colleagues have grown bored with complaining about how difficult it is to get students to do reading, and how they must take ever greater pains to keep students amused and engaged.

But it’s not only these practical considerations (on our part and our students’) that are worth noting. An equally important component is the reduction of so much of our teaching to political bottom lines, usually resting on identity issues. Why bother reading anything in detail if one can readily enough spot its politics and praise or blame it on that score alone?

By encouraging or capitulating to this perspective, professors in many humanities departments have in effect taught their students that the humanities do not matter, that attentiveness to reading is irrelevant, that the life of the mind (does anyone use that phrase these days?) has nothing to offer. Instead, what counts are attitudes – in particular attitudes toward race, class, gender, heterosexuality, etc. – and if we can discern these quickly, so much the better. Why shouldn’t this far more economical, and self-righteous, path not appeal to our students?

The well-known scholar and former MLA president Elaine Marks, whose work was instrumental in promoting feminist literary theory, in the years before her death in 2001 turned against the practice of reading guided by identity politics and the tireless insistence on “differences.” In 2000, she published an essay entitled “Feminism’s Perverse Effects,” in which she expressed her growing concern about the directions in which literary, cultural, ethnic and women’s studies had all been moving for some years.

Disillusioned with the practice of trolling literature and culture for signs of the ubiquitous -isms, Marks acknowledged her new-found sympathy with the arguments set forth by Harold Bloom in his much-maligned 1994 book The Western Canon. Like Bloom, she had come to lament students’ failure to respond to literature imaginatively, their habit of replacing knowledge of western culture with a ceaseless pursuit of signs of its villainy, and their inability to experience surprise and delight in a text. She was astonished, she wrote, to discover herself applauding Bloom’s words, “To read in the service of any ideology is not, in my judgment, to read at all.” But merely expressing such concerns, Marks complained, would stigmatize a scholar as a closet conservative and traitor.

The Suicide of the Humanities

And that was in 2000. Since then things have only gotten worse, as higher education increasingly and openly pledges itself to politics before all else, whether in the name of those elusive absolutes “diversity, inclusion, and social justice” – words constantly promoted by university administrators (and accompanied by an ever-expanding corpus of administrators tasked with overseeing these agendas) – or to protect the fragility of college students who claim to be unable to withstand the horrific offenses to their sensibilities that they manage to ferret out on America’s campuses.

Though some scholars may worry when they see the university diverting more and more resources to non-humanistic subjects, the fact remains that the suicide of the humanities is not occurring against but rather with the willing participation of many professors, who have long given up defending their own fields as worthy of study except as ersatz politics. But if that’s all the humanities are about, why not just abandon them and go straight for the real thing?

I worked in a trashy little bookstore that actually stocked great books (which didn’t pay our bills – the trash did) for the first year of my undergrad life. As a result of washing up upon this beach at such a tender time of life, approximately 85% of all the reading I did during the three years of undergrad (this was Canada) had absolutely nothing to do with course material, directly or even indirectly. What I could have done with an internet resource back then!

But the point of the narrative is this: I grew up as a writer’s son, became a staunch bookworm at the age of nine, whose challenge in life was to spend as much time carousing out of doors as possible, meanwhile stretching the elasticity of my breadth of interests at the same time.

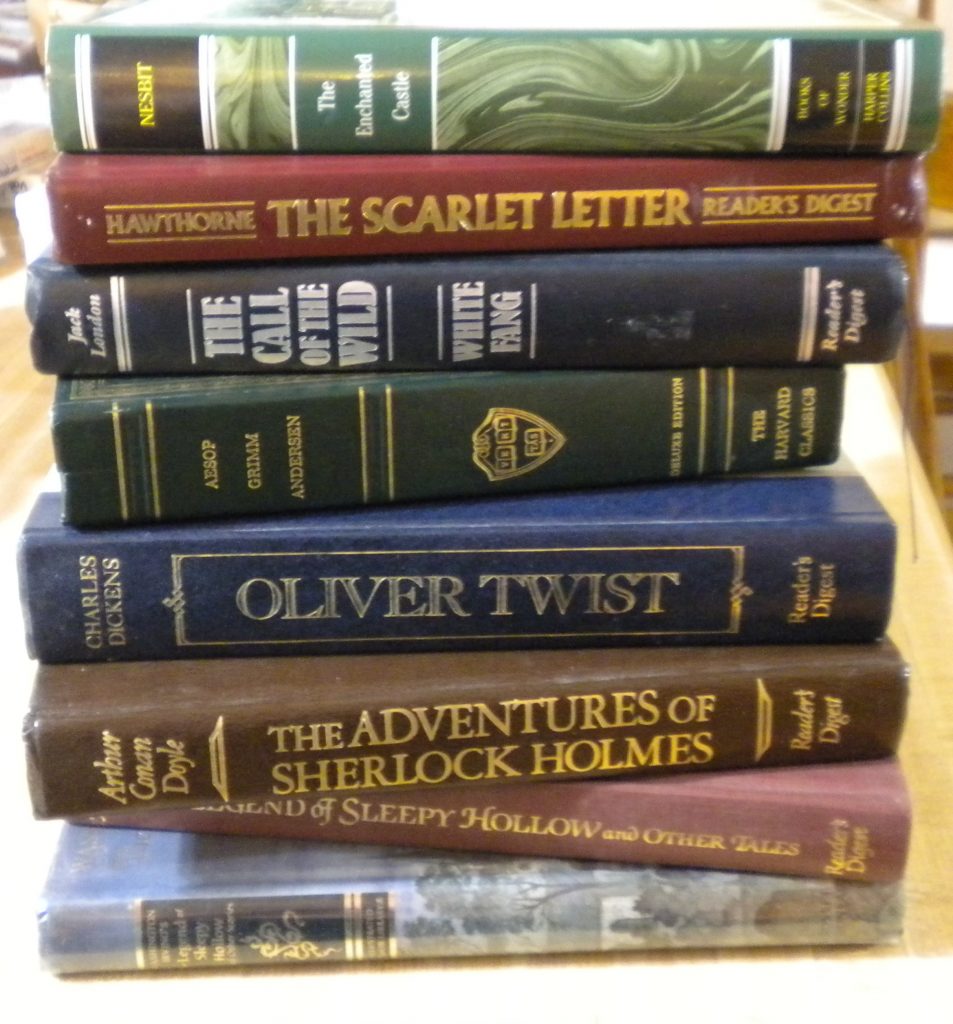

Books of course, were things of wonder. Feeding the insatiable hunger for information, stuff to find out about, curiosities to satisfy, and the activity of learning for its own sake.

What the hell happened to the relationship between kids and books in the past 5o years?

Nobody ever had to tell me that the rock solid foundation of a good education and a firm grounding in understanding the world I live in was based on the ability to read, to read well, to understand and grasp deeply the meaning in what I read, and to add endlessly and easily to the pile of things understood, starting with the theory of a book and its proof found in “real life.” The endless dance between those two things.

The relationship between a picture-less book and your own imagination pixelates the pallet and the canvas of an ever-expanding imagination. True, for the said purpose of never finding yourself in the embarrassing condition of boring yourself to death with your own company (or others, for that matter) but also for exponentially expanding outward the ability to think the way a BIg Bang moves. Outwards in a perfect circle to infinity.

Ms. Patai, big fan. I discovered you rather recently, and have always been astonished every time I read you and re-read you, that you had to have been a quarter century ahead of your time, and effortlessly so!

I find this article, and this blog’s over-arching theme, quite depressing. People escaping their personal responsibility while making excuses for poor choices appears to be quite prevelant on American campuses, and beyond. The time is now for you to reach down amd pull up your own boot straps.

I appreciated the Roger Ebert quote. It takes some extra work and hard thinking to maximize the moment.

Please keep posting these interesting articles and cerebral comments. Hopefully the incoming freshman classes at places like Yale, Claremont, Duke, College of Wooster, and others will improve upon the current situation by thinking more deeply in advance of professorial abuse.

I’ve been re-reading Vanity Fair (having recently finished Ivanhoe and The Grapes of Wrath for the first time), and I have to say, the time thing is a really big problem given that I have probably have close to or more than a hundred pages of course readings a week and my continued attempts to sustain an expansive television habit. Consequentially, even I who has far fewer time commitments than the vast majority of students resorted to the old “all night essay” trick.

One of my friends is taking a stage one history paper I did several years ago at the moment. When I did it, it felt as though there were maybe two other people in my twenty or so strong tutorial who were consistently doing all the readings (most of whom were prob. not history majors). It was actually really awkward getting my notes out for these tutorials so I tended to wait until after the tutorial had begun to get rolling.

With that exposition done, the point In addition to a 30%, we had two 10% open-book multi-choice tests (sounds piss easy, right? somehow the first one had an average mark of 58%). In contrast, my friend, presumably as a means of increasing attendance and commitment to the readings, has to write weekly five minute single-paragraph tests. I also had randomly scheduled longer single-paragraph tests two semesters ago for a stage two history paper, but those were aimed specifically at attendance. So, you can do things.

History is a bit different to English, though. I mean, even if you just did a tutorial on Vanity Fair up until Waterloo, that’s basically as long as a lot of books are in total. History books can also be very long but in general lectures serve to convey the scope of the topic and therefore the readings tend to favour articles or chapters. But even a history book is unlikely to have a Spark/Cliff notes version that you can refer to instead.

But, to an extent, I would suggest that a lot of people my age (c. 20) simply do not have the will to try, because quite often I don’t either… and while my (non-television) distractions are somewhat more intellectually stimulating than, say, “Sad Affleck” that’s ultimately what they are.