There was a time not so long ago when elite public institutions, such as the University of California (Berkeley), the University of Michigan, and the University of Wisconsin, more than held their own against competition from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and other elite private institutions.

Berkeley’s reputation for academic excellence in the 1950s and 60s was unsurpassed; indeed, in the mid-1960s many experts considered Berkeley to be the finest university in the world. Flagship universities in Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Virginia earned high rankings.

Related: How Our Universities Are Failing Us

Few private institutions could match the range of outstanding research programs offered at flagship state institutions, particularly in expensive fields like the sciences and engineering. Admission to these institutions was widely pursued by out-of-state students willing to pay premium tuition. With enrollments in excess of 25,000 and in some cases 40,000 students, these institutions dwarfed the privates in scale but delivered a great deal of educational “bang for the buck.” Degrees from Berkeley, Michigan, and Wisconsin were judged as equivalent to those from the top private institutions.

Today the situation is greatly changed. There is not a single public institution listed among the top 19 schools in the 2016 rankings by U.S. News & World Report. Berkeley ranked 20th, while Virginia and UCLA came in tied at 24 with Michigan at 29 and the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill) at 30. What happened over the last four or five decades to reverse the momentum in higher education from public to private institutions?

Christopher Newfield outlines what he thinks is the answer in his very interesting, carefully researched, but ultimately misguided book, The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them. Newfield, a professor of literature and American Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara, argues that we have engaged in a multi-decade campaign to “privatize” public universities by withdrawing public funding and replacing it with higher tuition funded by student debt.

He does not mean that public universities have been privatized in a literal sense but that they are increasingly expected to run like businesses delivering services to customers. From this point of view, universities mostly deliver private benefits and thus they should be paid for with private funds – primarily student tuition – and less and less by legislative appropriations.

Related: The 12 Reasons College Costs Keep Rising

A central casualty in this process has been the belief that universities deliver public benefits to society sufficient to justify large public investments. Newfield argues that public universities deliver all kinds of public benefits in addition to private benefits, such as technological innovations and scientific advances, medical breakthroughs, better overall health of the population, social literacy and tolerance, mobility, and rising living standards.

Such public benefits used to be taken for granted as recently as the 1960s and 1970s when politicians and the public at large generally agreed that the social returns from higher education justified substantial investments in public universities. Over the last several decades, he argues, that public vision gave way to what he calls a privatized vision of higher education.

Newfield tracks the collapse of this public vision by the steady decline over recent decades in legislative appropriations to support public universities. The figures he reports suggests that while this process may have begun in the 1980s it has accelerated in the past decade or so in just about every state in the union. Between 2008 and 2015, state appropriations for higher education declined by an average of close to 20 percent across the country, and by more than 25 percent in at least 15 states.

There were only three states – Alaska, North Dakota, and Wyoming – where appropriations actually increased. Obviously, this had much to do with the financial crisis and the slow recovery from it, but Newfield suggests that in reducing appropriations state legislatures took advantage in these years of the process of privatization that began decades earlier.

Public universities have responded by raising student tuition to cover costs, though Newfield points out that there exists no one-to-one relationship between declining appropriations and rising tuition. Indeed, in recent decades public universities have raised tuition much faster than legislatures have cut appropriations, and public institutions have raised tuition in tandem with private colleges and universities. Between 1980 and 2012, college tuition and fees increased more than ten-fold in nominal terms and 4 or 5 times in inflation-adjusted terms.

College tuition and fees increased during this period at almost twice the rate of medical care, three times the pace of housing costs, and almost five times the rate of the Consumer Price Index – in other words, at rates that could not be sustained absent the availability of credit to finance the rising costs. Thus student-loan debt has exploded in recent decades, growing from roughly $200 billion in the year 2000 to $800 billion in 2010 – and still growing thereafter.

Student loan debt now exceeds credit-card debt in the United States. Over this period, family disposable income has grown by roughly 60 percent while the volume of outstanding student loans has grown nearly 10 times more rapidly – or by more than 500 percent. These are staggering figures by any measure. Given the stagnation in family incomes in recent years, one wonders if those loans can ever be repaid.

What’s the answer? Newfield, in keeping with his thesis, thinks that we must first restore the idea that higher education is a public good deserving of substantial public investment. These more generous appropriations may require higher taxes, as Newfield acknowledges, but he points out that the costs for most taxpayers will be minimal and in any case easily affordable given in view of the savings most families will enjoy from the reduced expenses of college tuition and fees.

To give Newfield his due, he has written a serious book that backs up his thesis with an impressive array of fact and argument. His book contains a great deal of current information on trends in student debt, tuition increases, and legislative appropriations for public education. Whether or not readers agree with the overall thesis, they can at least agree that Newfield has made a good case for it, and for this reason has delivered a valuable book.

Many Americans for various reasons seem to long for the glory days of the 1950s and 1960s when, they believe, life was easier than today, families were more stable, good jobs more plentiful, and America was making steady progress year by year. Some on the right look back to that era with nostalgia for the conservative social values that prevailed, while others on the left would like to recover the good manufacturing jobs and strong labor unions that were then influential in the economic life of the nation.

It seems that Newfield is of a similar mind about that era, except that he would like to restore the public confidence and financial support that public universities enjoyed during that period. As with those other longings, Newfield’s is unrealistic and no longer attainable. We have moved on, and we are not going back.

In the first place, that period (from roughly 1950 to 1966) was a unique era in American life. The United States enjoyed rapid economic growth of between 4 and 6 percent per year, or something close to two or three times the rates of growth we have experienced over the past two decades. Economic growth and progressive taxes swelled the coffers of state and federal governments. The “baby boom” created large families with parents and grandparents willing to invest in children and their education.

Related: How Reform Conservatives Can Help Higher Ed

With few competitors in the public sector and a growing population of students seeking admission, public universities had a claim on public resources that they had never before enjoyed. Universities were, moreover, widely respected by the public for the quality of the education they provided and the seriousness with which university presidents, professors, and administrators seemed to go about their business. These conditions have long since gone the way of the electric typewriter and the family station wagon.

In the heyday of public universities, state governments spent the bulk of their funds on just a few functions – primarily transportation, public safety and corrections, and higher education. During this period, public universities had few competitors for state funds and, indeed, with their alumni well represented in the legislatures and the “baby boom” generation headed off to college, they were well positioned to lay claim to a rising share of state budgets. Across the nation, somewhere close to 20 percent of state budgets flowed into the public universities at a time when public employee pensions, health care, and K-12 education were still minor items in state budgets.

That is no longer the case. Public universities now face an unfriendly political environment due to the expansion of state governmental functions since the 1960s. States now have many functions and constituent groups that command more money and attention. According to a report by t682he National Association of State Budget Officers, Medicaid accounted for 26 percent and K-12 education another 20 percent of total state expenditures in 2014, proportions that have been expanding steadily for years.

A Scramble for Public Dollars

Thus, nearly half of all state expenditures are now allocated to two programs that did not command any state resources in the 1950s and 1960s. Several years ago voters in California approved a mandate requiring 40 percent of all state funds to be allocated to K-12 education. The well-connected advocates and interest groups that support these programs are unlikely to permit those shares to decline. Meanwhile, public employee pensions now command about 5 percent of state spending but, due to years of underfunding and deferred payments to the funds, some experts expect that share to grow to grow to perhaps 10 or 12 percent in the decades ahead.

By contrast, higher education now lays claim to just 10 percent of state expenditures, or roughly half the share allocated to this sector in the 1950s and1960s. In the scramble for public dollars, public universities must now contend with public-employee unions, court orders and referenda directing ever more public funds to K-12 education, and the lure of federal matching funds for Medicaid, welfare, and other federally subsidized programs.

Given political realities, they are unlikely to win many of these battles. Indeed, it is not clear that they should. After all, the professors and administrators who complain about reduced public expenditures were generally among those calling for more state funding of the kinds of public programs that have drained resources from higher education.

In addition, public universities today must share public appropriations with an expanding complex of regional campuses and community colleges that barely existed in the 1950s and 1960s. The California legislature created an elaborate and expensive three-tiered system of research universities, regional universities, and community colleges in the early 1960s just as the University of California was reaching a pinnacle of influence and prestige. Other states expanded in parallel ways. Michigan now supports 45 distinct institutions of higher learning, all in financial competition with the state’s two flagship public institutions. Wisconsin supports 26 such institutions, in addition to its flagship campus in Madison.

These second and third-tier institutions have representatives lobbying the legislatures and demanding their share of state higher-education dollars. In addition, more and more teachers at the lower-tier four-year universities and community colleges are leveraging their power by joining unions that bargain and lobby in their behalf. Professors at elite institutions have so far resisted the pressures to unionize.

As Newfield acknowledges, public universities have not been on a starvation diet, mainly because they have been able to pass along rising costs to students and parents. Most public universities have dramatically increased the number of courses in their catalogs and the number of centers, institutes, and programs that must be paid for. The number of administrators employed on public campuses has exploded nearly as rapidly as student debt.

Between 1975 and 2011, the number of faculty at colleges and universities across the nation grew by just 23 percent, while the number of full-time administrators grew by 369 percent – or, put differently, colleges and universities hired 16 new administrators during this period for every new professor hired. To the extent this is a problem – and there can be little doubt that it is a problem – it represents a self-inflicted wound. No one forced trustees and presidents to participate in a misallocation of resources on this scale.

Finally, is it really true that public universities confer a public benefit of the kind justifying expanded public support? That question deserves some real examination and debate. There can be little doubt that public universities, along with most private institutions as well, have evolved into hothouses for left-wing identity politics. Numerous studies have demonstrated that liberal and leftist professors outnumber conservatives by a ratio of between 10 and 20 to 1, and Democrats outnumber Republicans by a similar ratio.

That might be an acceptable situation in an environment where practitioners are guided by professional standards, but that is no longer the case on the American campus. Large numbers of professors, administrators, and student advocates have been politicized to an unhealthy degree. If there is a “great mistake” in higher education, then it more accurately relates to the hyper-politicization of the contemporary campus.

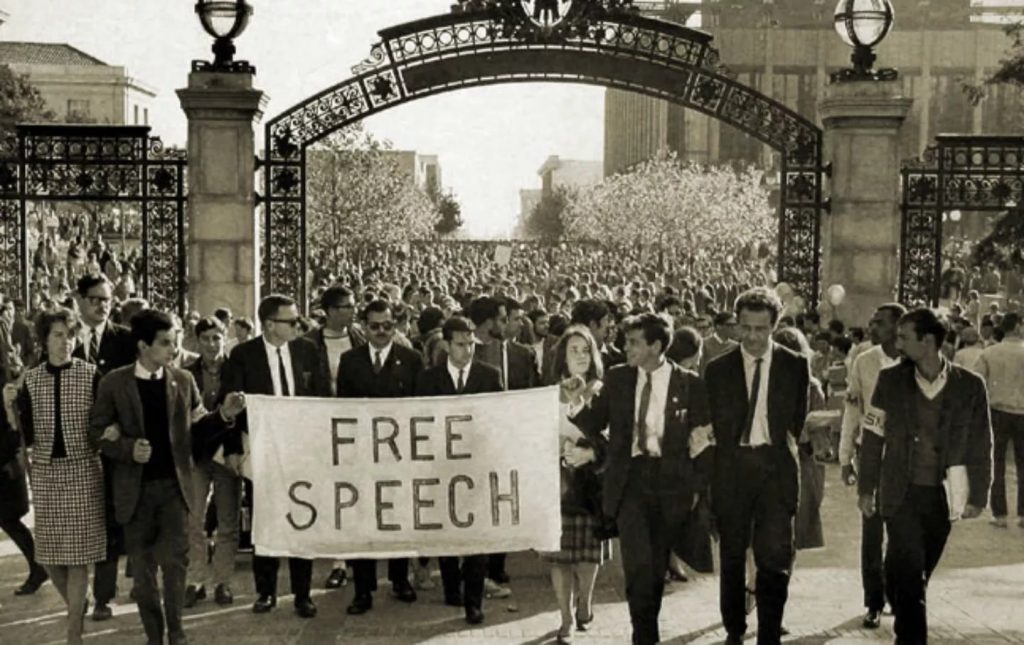

When colleges and universities are mentioned in the press today, the story is likely about a speaker who has been harassed or disinvited from campus, or students demonstrating for “safe spaces” on campus to insulate themselves from discordant opinions, or for more courses and programs on women, minority groups, the environment, and other causes associated with the political left. Judging by the statements of many faculty, administrators, and student representatives, they would like to criminalize or at least delegitimize the opinions of conservative and religious Americans, and in the process make certain that those views are never expressed on the campus.

Related: How Soft Censorship Works at College

This kind of thing has been going on now on leading campuses for three or four decades. Should anyone be surprised, then, when taxpayers and legislators ask why they should subsidize these politically one-sided institutions? Universities – public and private – are increasingly viewed as partisan institutions, strongly attached to the Democratic Party and, therefore, no longer seen as enterprises that serve the public good. That may be unfortunate, as one might agree, but it is nevertheless the case.

Instead of restoring public subsidies to universities, as Newfield says we must, it makes more sense to move further in the direction of privatization by “voucherizing” the higher-education industry–providing vouchers at public expense for students to spend at the institutions of their choice. This would promote greater competition among campuses such that (hopefully) useless and redundant programs and employees would be eliminated out of the need to cut costs and respond to consumer demand.

The university sector is failing the society that supports it – of this, there can no longer be any doubt. “Voucherizing” higher education would represent a radical step into the unknown, but we are fast reaching a point where radical steps are called for.

Hi, James Piereson

I am curious where do you get this quote – Newfield says we must, it makes more sense to move further in the direction of privatization by “voucherizing” the higher-education industry–providing vouchers at public expense for students to spend at the institutions of their choice.

Best,

Simon

This article covers why I oppose “free” college:

1. Universities operate inefficiently, particularly with a bloated payroll of superfluous administrators & deans.

2. Universities condone violations of civil rights, particularly with regard to freedoms of speech, assembly, and conscience.

3. Related to #2, universities are hyper-politicized.

4. Universities offer useless, ideological degree programs such as racial studies, ethnic studies, women’s studies, and gender studies.