Should all-black colleges exist in 2010? No, some say. After all, it’s been almost fifty years since segregation was outlawed in America. And most Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are of also-ran status, doing their best, but hardly the bastions of excellence that so many were in the old days. Graduation rates are low and not one of them made the top half of Forbes’ ranking of more than 600 schools nationwide. Of the “black Ivies”– Morehouse, Spelman and Howard– only Spelman made US News and World Report’s top 100 list of Liberal Arts colleges in 2010. Graduates of HBCUs don’t make as much money, on average, as their equivalents who went to mainstream schools.

Should all-black colleges exist in 2010? No, some say. After all, it’s been almost fifty years since segregation was outlawed in America. And most Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are of also-ran status, doing their best, but hardly the bastions of excellence that so many were in the old days. Graduation rates are low and not one of them made the top half of Forbes’ ranking of more than 600 schools nationwide. Of the “black Ivies”– Morehouse, Spelman and Howard– only Spelman made US News and World Report’s top 100 list of Liberal Arts colleges in 2010. Graduates of HBCUs don’t make as much money, on average, as their equivalents who went to mainstream schools.

To many, all of this means it’s time to just shut these schools down. That argument, if based solely on the facts above, is ultimately an ill-considered reaction, unlikely, I suspect, from anyone who has ever spent time at one of the schools.

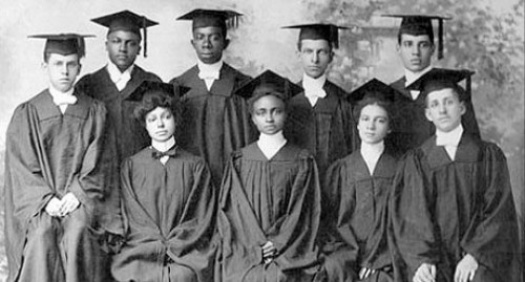

Yet it is hardly wrong to start conceiving of HBCUs as time-limited. I don’t find that easy to write as a black person – but I do find it true. I presume all agree that HBCUs were necessary in the days of legalized segregation, and that they produced legions of top-rate black thinkers and professionals. The question is what their value is today.

Since 1964, the justification for HBCUs has required a certain amount of cognitive dissonance. We have been taught for decades that we are moral troglodytes not to understand that racial diversity is key to a quality college education – and yet the notion of schools where everybody is black is also supposed to warm our hearts. It would appear that when we cherish black students for lending diversity to campuses, we are talking about a benefit to the white kids – because apparently, it’s no problem if black kids go to colleges where everybody looks just like them.We are to shudder at the thought of all-black public schools as “segregated” – but then we are to cry “racism” when someone criticizes all-black colleges.

Since 1964, the justification for HBCUs has required a certain amount of cognitive dissonance. We have been taught for decades that we are moral troglodytes not to understand that racial diversity is key to a quality college education – and yet the notion of schools where everybody is black is also supposed to warm our hearts. It would appear that when we cherish black students for lending diversity to campuses, we are talking about a benefit to the white kids – because apparently, it’s no problem if black kids go to colleges where everybody looks just like them.We are to shudder at the thought of all-black public schools as “segregated” – but then we are to cry “racism” when someone criticizes all-black colleges.

Obviously none of this makes any sense. These are not things that “make you think” – their acceptance requires suspension of thinking. The only question is whether something else justifies the doubletalk. And the truth is that even after 1964, something has.

Namely, racism. It has hardly vanished with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, not even in its most overt form. Black people in 1970 did not feel like they were living in a different world from 1964, because they weren’t. Stuart Buck in his excellent book on why black students started accusing black nerds of “acting white” records the hostility black students faced, for example, from whites when schools were desegregated in the sixties.

And even by the eighties, when most naked racist abuse had faded, HBCUs played an important role. Black students there could experience a warmth, an ease of acceptance, a complete freedom from wondering whether whites thought of them as less competent or alien. In her mostly white high school, my sister never had a date and barely had friends. As soon as she hit Spelman, she had both. And from my visits there and later to Morehouse, I can see that I would have had a different and better social experience at Morehouse than at the schools I attended.

And even by the eighties, when most naked racist abuse had faded, HBCUs played an important role. Black students there could experience a warmth, an ease of acceptance, a complete freedom from wondering whether whites thought of them as less competent or alien. In her mostly white high school, my sister never had a date and barely had friends. As soon as she hit Spelman, she had both. And from my visits there and later to Morehouse, I can see that I would have had a different and better social experience at Morehouse than at the schools I attended.

The question has become, then, whether the HBCU experience remains as significantly more comfortable than the mainstream one as it was a generation ago. When it gets to the point that black students at mainstream schools are not having a significantly oppressed or even uncomfortable experience, then we return to how fragile the justification for HBCUs is on legal or logical grounds. How do we define significant? Well, we can start with the fact that no one is suggesting building all-Asian or all-Latino campuses any time soon, despite students of both extraction amply attesting to racism in the college environment.

As always, pulling the camera back is key. Imagine how most of us would feel to find out that Turks in Germany often attended all-Turkish colleges. Our natural assumption would be that Germans wanted it that way. When told that they did not, many would maintain a suspicion that there was a desire of that sort lurking “somewhere,” “subtly,” “institutionally.”

The situation is the same with the descendants of African slaves in America in 2010. And here we must address a likely objection: “HBCUs will be necessary as long as there is racism in the United States.” If the Turks made the equivalent claim, most of us would process it as utopian, and wonder why these Turks felt that they could only learn under ideal conditions. It would sound, let’s face it, weak, unprideful. Moreover, confronted with the majority of Turks who did not feel that the absence of racism was necessary to an effective education, none of us would be surprised.

The essence of the case for HBCUs, then, is that we cannot think of them as a permanent situation. For example, to convert the smaller ones, often struggling to even stay afloat, to solid vocational schools would be a thoroughly pro-black policy. Decry that as a return to Booker T. Washington and his buckets, and then remember how much we value “people who work with their hands” as well as how high the salaries of plumbers and air conditioning technicians are.

Then with the tonier HBCUs, a time could come when they are completely multiracial – or, to put it in a more attractive way, they could start to “look like America.” In stages, to be sure. But in line with the different world that we are in, and how much more different it is always becoming.

Let’s say that in fifty years, black students are content with the degree of fellowship that one gains in clubs and theme houses. Once the clubs and dorms were all a couple of generations had known, they would seem like utterly sufficient sources of bonding, just as they do for Asian and other students. Who would then suggest that black students instead have whole campuses to themselves?

Change is hard. Mission creep and habit are eternal challenges. But that means that we should always have expected that at a certain point, our insistence on HBCUs’ continued existence would be based less on what they are than on the fact that they have been here so long. That point, it would seem, has come.

If black students want to go to a racially segregated private college for whatever reason that is their right. Historically, all the HBCUs are poor academic performers, but their students do get some benefits, and the HBCUs serve some students who would not be admitted to an integrated institution and who would not perform well there.

By the way, in private institutions, I have no problem with segregation by race, gender, religion, social class, etc., etc. The issue is the right of free association, which controls.

The case of public institutions, which are funded by everyone, and which execute public policy, is different. While some internal segregation always occurs because of student/faculty preferences, the policy should be that admissions and formal classes are open to all.