Gary Fethke’s recent op-ed Why Does Tuition Go Up? Because Taxpayer Support Goes Down in The Chronicle of Higher Education is an enjoyable read. Rather than dismiss the opposing side’s argument with straw men, as is so common these days, Fethke presents it faithfully and gives it due consideration, which is a breath of fresh air.

Having said that, I have to disagree with Fethke’s main point. He argues that “rising tuition is the obvious consequence of declining state appropriations…” and that “Students are required to pay more because taxpayers are paying less–it’s that simple.”

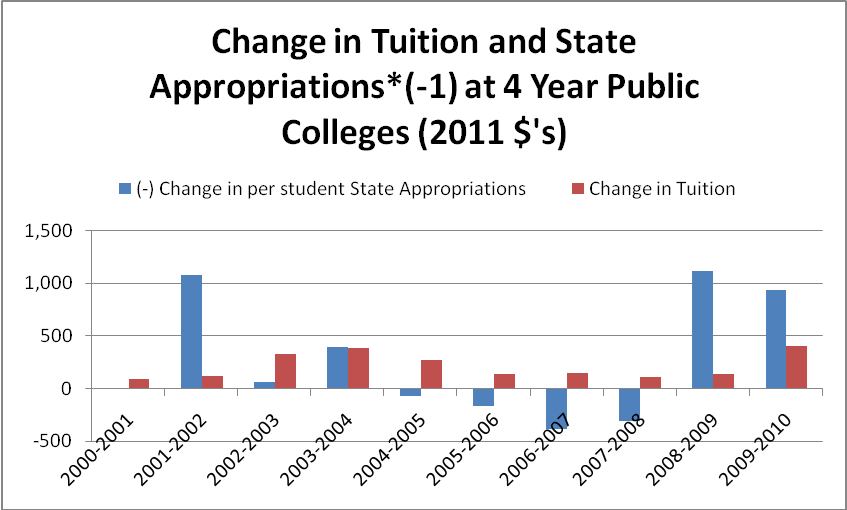

As luck would have it, I’ve been looking at precisely this issue, and the data doesn’t support this conclusion. The chart below shows the enrollment weighted national average change in per student state appropriations and tuition at public four-year colleges by academic year. I’ve multiplied state appropriations by negative one, so that if a $1 cut in state appropriations leads to a $1 increase in tuition, the two bars should be exactly equal (rather than being mirror images).

It is clear that the two bars are not equal. The 2003-2004 changes are the only ones that fit Fethke’s story, while the rest show a tenuous relationship (correlation of 0.21). Particularly striking are the increases in tuition even when state appropriations were increasing (2000-2001 and 2004-05 through 2007-08). The conclusion is that historically, changes in tuition were not driven by changes in state appropriations. Examining longer time periods rather than yearly changes does strengthen the connection, but it is still nowhere near 1 to 1 (e.g. a one dollar change in appropriations is associated with only a $0.06 to $0.15 change in tuition in the long run).

So if changes in state appropriations don’t explain changes in tuition, what does? Some would argue that faculty salaries (Baumol’s cost disease) or institutional aid (college-funded scholarships and discounts) are important, but forthcoming examinations show that they are negligible and minor respectively. One factor that Fethke dismisses is the idea that increases in financial aid lead to higher tuition, known as the Bennett Hypothesis. Fethke argues that

Competition defeats the Bennett hypothesis by reducing a university’s ability to raise tuition in response to increases in federal grants…

However, in my recent paper, I find that isn’t the case. After updating the theory, a revised Bennett hypothesis is shown to be a big factor in explaining why tuition increases, largely because competition in higher education is dysfunctional:

We would not expect bread producers to simply spend more making bread until they had captured the entire subsidy, so why does this happen in higher education?

The key difference between higher education and the bread industry is the nature of competition: In higher education, colleges essentially compete in a zero-sum game for relative standing… Since high quality inputs are costly, and colleges are playing a zero-sum game of relative position, there is no limit to what college[s] will spend in the pursuit of excellence…

In contrast, bread producers compete based on value (roughly defined as quality divided by price, both components of which are observable to consumers)… Bread-makers seek to make the bread with the highest value, they do not seek to spend as much as possible in the pursuit of the highest quality bread regardless of cost… [so] there is no need to worry that subsidizing bread will lead to higher bread prices and capture of the subsidy by bread makers…

Whether you buy my argument that the new and improved Bennett Hypothesis is an important factor in explaining why tuition increases or not, it is clear that tuition increases cannot be explained by changes in state appropriations.

That is why ACTA has been vigorously urging college trustees to reject the notion that declines in state appropriations necessitate balancing the budget through tuition increases. Holding the line on tuition is essential to prevent shifting the burden of rising costs to the very students the institution serves. More importantly, it will place the imperative on all stakeholders to work together toward solutions that ensure that higher education remains efficient, effective, and accessible.

—————-

Andrew Gillen is the Senior Researcher for the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, a higher-education non-profit dedicated to academic excellence.

You cannot get a credit for tuition that is paid by your employer, unless the employer includes the amount of tuition in your taxable wages. It is unlikely that your employer is doing this, since the employer would have to pay payroll taxes on this money. If you have additional tuition and fees that you paid for which you were not reimbursed, you can get the Lifetime Learning Credit. You may alternately take a Tuition and Fees deduction for tuition you paid. There are income limits to both of these tax benefits. Since you education appears to be work-related, your unreimbursed expenses related to your education may be deducted as unreimbursed employee expenses on Schedule A, subject to 2% of your AGI. These expenses include your transportation to class, parking, equipment, books, and supplies. You can also take the Schedule A deduction for any amounts that you cannot use for the LLC or Tuition and Fees deduction.

Having taught at the nation’s largest urban public university, I have a more important question. Do academic standards decline because tuition increases?

Frederick K. Lang

Professor Emeritus of English

Brooklyn College

City University of New York