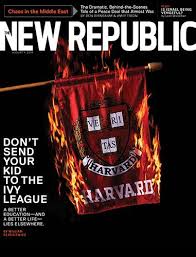

William Deresiewicz has a provocative piece of advice in this month’s New Republic: “Don’t Send Your Kid to the Ivy League.” Deresiewicz, a Columbia graduate and former Yale professor, argues that elite institutions often produce students who are entitled and lack purpose. He also suggests that elite schools promote inequality by catering mostly to high-income students. To fix these problems, he recommends sending students to liberal arts colleges, changing affirmative action to a class- rather than race-based system, and increasing funding to public higher education.

Is his diagnosis correct? Will his remedies actually improve higher education? We asked a distinguished panel for their thoughts:

Mr. Deresiewicz’s article is helpful and insightful in many ways, but badly flawed as an analysis of the problems of higher education in America and in the elite institutions in particular. He is certainly right to say that affirmative action, to the extent it is practiced at all, should be based on class and family income rather than on race, gender, or ethnicity; he is also on the mark in suggesting that achievement and success have replaced religion and virtue as aspirational goals of striving upper middle class families; and he is correct in pointing out that elite institutions have dissolved their liberal arts curricula in favor of a mish mash of trendy or technocratic courses designed for the comfort of faculty, the vocational goals of undergraduates, or the ideological prejudices of both.

But he is wrong to think that that these observations apply only or mainly to Ivy League institutions; wrong also in claiming that families can circumvent these defects by sending their children to public universities or small liberal arts colleges; and wrong once more in asserting that the problems of elite institutions arise from their emphasis on merit and achievement. The most disappointing aspect of his article is found the sophomoric conclusion that what we need in higher education is more democracy – when in fact this is the source of many of the problems he identifies.

Mr. Deresiewicz chastises Ivy League institutions because (as he thinks) they are undemocratic, meritocratic, and “elitist.” He also seems to think –illogically– that this is why they have abandoned the liberal arts. This is not true at all. The liberal arts, understood as the education of the whole person through the study of the great works of the past, have been banished everywhere, except at a few hold out institutions where undergraduate education is taken seriously. One will not find a serious liberal arts curriculum at any of the major state universities, nor at any of the supposedly “liberal arts” colleges that he mentions in his article. One could debate why this has happened. One major cause is the hare-brained idea that the liberal arts are in some way incompatible with democracy or hostile to the aspirations of women and minorities.

Mr. Deresiewicz might have taken his argument a step further to reflect on some of its more obvious implications. The current President of the United States is a graduate of two Ivy League Institutions (Columbia and Harvard Law School); his predecessor similarly had two Ivy League degrees (from Yale College and Harvard Business School); his predecessor in turn was a graduate of Yale Law School, and his predecessor from Yale College. Every U.S. president since 1988 has held an Ivy League degree. All nine members of the U.S. Supreme Court are graduates of Ivy League law schools (eight of them from Harvard or Yale), and several have undergraduate degrees from these same institutions. Of the 100 current members of the U.S. Senate, 18 have degrees from Harvard and Yale alone. All have won their positions through a competitive democratic process and in a culture in which the rhetoric of democracy and equality is expressed more insistently than ever before in our history.

How and why has this happened? How is it that graduates of the most “elite” institutions have mastered the arts of democracy far more effectively than graduates of less selective and more “democratic” institutions? If these leaders are “hollow men and women,” as Mr. Deresiewicz implies, then what does that say about the voting public that has put them into office? These are good questions, but ones the author cannot answer given the framework he has adopted.

James Piereson is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

Deresiewicz’s article has a very promising title. In his mind, today’s students at elite colleges are “zombies.” They go through life orbiting or floating, unable to enter the real world of beings born to know, love, and die. There is, however, nothing new about such a description. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn perceived that just beneath the surface of what Deresiewicz calls our “technocratic” pragmatism lay an “overwhelming loneliness” that “gave rise to the howl of existentialism.” The reason for our howling in the midst of abundance is our failed attempt, Solzhenitsyn explains, to neglect the soul.

Deresiewicz’s description of what he sees in elite college graduates isn’t so different from Solzhenitsyn’s: “Look beneath the façade of seamless well-adjustment, and what you often find are toxic levels of fear, anxiety, and depression, of emptiness and aimless and isolation.” It’s hard to know what he means by “toxic.” The only evidence he presents is “that self-reports of emotional well-being [in a large-scale survey of college freshmen] have fallen to the lowest level in the study’s 25-year history.”

Whatever may be going on with freshmen, all the evidence we actually have about the lives of elite college graduates is much more reassuring. Indeed, their families are becoming more stable. If you want “toxic,” look at the increasingly pathological family lives of the lower part of our middle class. The truth is things aren’t all that bad—and maybe getting better—for the personal and relational lives of most prosperous and sophisticated Americans.

Deresiewicz is on firmer ground when he says that members of our cognitive elite are too complacent about their places in the world and are unable to practice charity or generosity. And he’s certainly right that, in the best cases, colleges should assist students in taking themselves seriously as beings with souls.

The highpoint of his article is when Deresiewicz observes that relatively obscure religious colleges do a better job than any of the Ivies or other elite institutions in focusing students on cultivating their souls by thinking deeply about who they are and what they’re supposed to do. He doesn’t do New Republic readers the service of naming any of those colleges. So I’ll mention some: Villanova, Thomas Aquinas, Baylor, University of Dallas, BYU, Notre Dame, Eastern, St. John’s (not religious, actually), and Providence. Even at those schools, “soulful” higher education is usually just an option, but in our time we can’t expect “liberal education” to be more than one niche among many. He might also have mentioned schools that still have a somewhat classical focus on the proud relationship between moral and intellectual virtue, such as Morehouse and Hampden-Sydney.

Deresiewicz is surely right to suggest that Ivies and comparable elite schools such as Haverford probably will not get much better. Along with the technocratic mindset there’s the omnipresence of political correctness, which is probably even more hostile to the idea of higher education as the discovery of wisdom and the practice of virtue. The truth is that there’s more intellectual diversity in our better religious schools than there is in any of our top-rated ones.

The most disappointing feature of Deresiewicz’s article is its conclusion: He says the ticket is to spend a lot more public money on state schools. The democratic solution is to raise them to the standard of excellence we associate with the Ivies. It might be true that such state schools would be graced by more authentic socioeconomic diversity. But why would they do better than the Ivies in avoiding the technocratic and politically-correct obstacles to educating students with their souls in mind? Deresiewicz doesn’t address the most pressing issue in higher education—fending off the two forms of zombie standardization that threaten the genuine diversity which has been, so far, the saving grace of American higher education.

Peter Augustine Lawler is Dana Professor of Government at Berry College.

William Deresiewicz deftly skewers the pretensions of elite education. Although he says little that we haven’t heard from other critics, he offers a useful reminder that Harvard, Yale, and Princeton are about status as much as learning. Yes, Deresiewicz’s depiction of undergraduate anxiety and faculty indifference is a caricature: there are more joyful students and passionate teachers than his dutiful caveats allow. In order to be effective, however, caricature must exaggerate something real.

But the argument suffers from a lack of historical context. More than a century ago, Henry Adams dismissed the Harvard of his student days as a gentleman’s idyll and the Harvard of his professorial career as a way-station for young men in a hurry to make fortunes out West. Is elite education today really less fulfilling? Deresiewicz gives few reasons to think so.

Deresiewicz is also unreasonably surprised to discover that the function of elite education is to consolidate the upper-middle class (the truly rich or pedigreed don’t worry about fancy degrees). Sure, Goldman Sachs recruits its executives from Princeton—who then send their children back in turn. The British civil service did the same thing with Oxford and Cambridge. Deresiewicz contends that “the education system has to act to mitigate the class system, not reproduce it.” You don’t have to be a Marxist to understand why this argument is naïve.

But the weakest part of the essay is its discussion of alternatives. Deresiewicz is torn between his instincts as teacher, and his egalitarian politics. The teacher in him knows that “real educational values” flourish best at liberal arts colleges and religious schools, where small groups of students read real books with professors who consider teaching an essential part of their job. His political conscience tells him that the solution is public universities, where education is “impersonal” but the daughters of physicians enjoy the “experiential learning” that comes from sitting next to the sons of plumbers.

The tension between these alternatives leads Deresiewicz to offer contradictory advice to prospective students and their parents. Sometimes he urges aspiring Ivy Leaguers to consider highly selective, if not quite top-tier colleges such as Reed. At other points, he suggests that they would be better off at, say, Penn State. But Reed students don’t encounter the diversity Deresiewicz wants, while Penn Staters don’t get the liberal education. So neither of these alternatives solves the problems that Deresiewicz identifies.

On a more basic level, Deresiewicz’s critique is unsatisfactory because he’s more invested in elite education than he realizes. True, he’s become a critic of the system’s excesses and distortions. But he retains its central assumption: that the place where one spends a few years as an undergraduate defines one’s life.

But that simply isn’t true. Students who work hard at serious courses, graduate, and don’t get into heavy debt will probably be fine no matter where they go or what they study. The real alternative to the Ivy League rat race is to accept that college is not such a big deal, unless you’re dead set on working in a glamour industry in a fashionable city. But I’d be surprised to find that argument in the pages of The New Republic.

Samuel Goldman is Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University.

Oh, go ahead. Take a chance. Send your kid to the Ivy League. The world won’t come to an end.

Your son or daughter will get a middling good education, some swell friends, a glittering credential, and improved chances of professional success and personal prosperity. There are indeed better things than those in life. One can strive to create great art or to found a new industry. But many worse ones too.

Deresiewicz is a class warrior. His key idea is, “The education system has to act to mitigate the class system, not reproduce it.” He would prefer colleges to preside over a fundamental rearrangement of the American social order. The Deresiewicz regime would abolish the “upper middle class” dream of the Ivy League and turn these institutions into a Sim City of the dis-privileged. The requisite mix would presumably be a nicely balanced collection of kids from the inner city, Appalachian coal towns made destitute by new EPA rules, hamlets bypassed by the interstate, Indian reservations sans casinos, and so on.

To be sure, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton ought to be open to individuals who, overcoming the odds, rise from any of these circumstances to show they can compete at the intellectual level demanded by such institutions. It may not be their best choice but it is a legitimate aspiration.

But it is silly to urge that colleges “rethink their conception of merit.” By Deresiewicz’s expert witness, Ivy League admissions are dominated by the effort to find academically gifted students who also have incredible determination to succeed and some imaginative capacity to market themselves. The few who best meet these requirements then become part of a community that puts an extraordinary premium on certain kinds of academic success. But such overachievers are often stunted in other areas of personal development.

No surprise there. The pursuit of a very high level of skills in any area means the neglect of others. The best ballerinas are often woefully ignorant of the Greek classics. First draft NFL picks are notoriously deficient in multivariate calculus. It’s a cruel world.

What exactly do the privileged Ivy Leaguers sacrifice? Deresiewicz’s answer: psychological health, intellectual curiosity, passion, and creativity. His Ivy Leaguers are “anxious, timid, lost,” and suffer from “toxic levels of fear, anxiety, and depression, of emptiness and aimlessness and isolation.”

Actually, they are suffering from postmodern secularism and a cultural over-emphasis on personal autonomy. They attend universities that have no core conception of the good other than success itself. Changing admissions criteria won’t fix that. The problem lies deeper. To upend the “class hierarchy” in America in order to fend off the discontents of such students is akin to cutting down a redwood tree to make a backscratcher.

Deresiewicz wants to cut that tree down in any case. The unhappiness of the academic overachievers is just a pretext.

Peter Wood is President of the National Association of Scholars.

Some left-wing critics might call William Deresiewicz a condescending elitist who has spent decades as an undergraduate, graduate student, and professor at Ivy League universities, and now tells his fellow elitists that they ought to go slumming at public colleges to experience the diversity of middle-class students in order to make it easier to converse with their plumber. But that would be a caricature of Deresiewicz’s essay, which is a thoughtful critique of elite universities and a wise call for a better system of higher education. Perhaps it takes a member of the elite to inform his fellow elitists about the flaws of the Ivy League and the dangers of a college system that enhances inequality instead of fighting it.

Still, at times, Deresiewicz has almost a naïve vision of the noble savages he thinks can be found on America’s lesser campuses: “Kids at less prestigious schools are apt to be more interesting, more curious, more open, and far less entitled and competitive.” This line strikes me as complete nonsense, the kind of glorifying of the poor as “real people” by thinkers who have spent their lives around elite universities. The truth is that kids at less prestigious schools are, on average, less curious, less open, and less interesting. That’s a product of their inferior education. Our unequal system is evil, but not because less prestigious colleges are full of better students and nicer people.

As you move down the ladder of prestige, students and colleges have fewer resources. Students are more focused on career-oriented studies, less prepared for intellectual work, and more often distracted by the job(s) they hold in order to pay for college. There are always exceptions to the rule, but curiosity and openness are a luxury in our education system, and more likely found at elite institutions.

When Deresiewicz advises students to skip the Ivy League, he ignores how much elitist discrimination there is in academia and business. The prejudice in graduate school admissions and faculty hiring in favor of elite universities is overwhelming. I doubt that Deresiewicz would have gotten his former job as a professor at Yale if he had received his B.A. and Ph.D. from an average public university instead of Columbia.

Deresiewicz seems to think that so many graduates of elite colleges go into finance or consulting because their minds are narrowed by their college education. In reality, students from all types of colleges would love these high-paying jobs, but hiring discrimination in favor of elite colleges is too powerful. So it’s easy to tell people to skip the Ivy League, but not many students will do it because the negative consequences to skipping the Ivy League are quite real.

Deresiewicz is right to call upon elite colleges to end legacy and athlete preferences, and to admit applicants for their own accomplishments rather than rewarding the rich students for a pile of parental-funded extracurriculars. But Deresiewicz actually does too little to challenge the elite status quo.

He should be telling rich donors and foundations to stop tossing money at wealthy elite colleges, and give it instead to the public colleges that need it the most and use it the most efficiently. He should be telling politicians to stop funding elite private colleges with grants and subsidized loans and tax credits, and spend public money on good public colleges. Instead of worrying about the emotional well-being of elite students overstressed by too much academic work, he should worry that most students at all levels are understressed by low standards.

It’s tempting to imagine that our higher education system is failing rich and poor students alike, since this would increase the pressure to change it. But the truth is that the wealthy aren’t being miseducated; they’re reaping the educational benefits of an unequal system.

While Deresiewicz’s concluding plan for educating the 99% (free, quality, public higher education) is thoroughly admirable, he’s fallen into the same elitist trap he criticizes. Instead of focusing on how to improve the quality of affordable public colleges, his essay (and his new book) is too obsessed with the education of elites to give the rest of us more than a distant glance from the top of the ivory tower.

John K. Wilson is the author of Patriotic Correctness: Academic Freedom and Its Enemies, the co-editor of AcademeBlog.org, and a Ph.D. student in higher education at Illinois State University.

Professor Deresiewicz is groping to explain an intuition he has developed based on his experience. It may not be precisely accurate and his prescription may be off base, but it rings with the essence of truth. One commentator’s response that Ivy Leaguers are disproportionately Presidents, Supreme Court Judges and Senators rather than undermining the Professor’s argument, reinforces the basic point. There is a self-fulfilling elitism that pervades society. Further, by all accounts these hyper-success driven drones on Wall Street and in government have done more than their fair share in presiding over the general decline of the United States through greed, graft and political dissimulation. Further, the Ivy obsession of many middle and upper-middle class folks speaks to a reality that they fully understand – the deck is stacked in favor of those who are part of the Ivy family. Both in business and government, the sheep have the reigns and help their fellow sheep perpetuate their power and elitism. There is no irony lost on the fact that the Ivies are systematically discriminating against Asian Americans as a class by rejecting highly qualified and superior academically performing students in disproportionate numbers. This, in itself, demonstrates, Ivy elitism is not merely based on academic prowess but “other factors” that include ensuring admission to those who “fit” their portrait of who should be their successors. The average Ivy league student is comprised of three groups: (1) the very wealthy and/or politically connected, (2) academically suitable athletes needed to compete on the field, and (3) “preferred” minorities as they play their part in advancing generally less qualified black and Hispanic minorities in the interest of social engineering. Literally thousands of equally or more qualified students are systematically excluded in shrewdly designed subjective criterion that choose the winners and losers. To assume that Ivy league students are the cream of the crop is an outright fallacy.

One need only look on Wall Street and Washington DC to find an abundance of hollowed out suits with Ivy league credentials puffed up by the assurance that they are entitled by parchment on a wall. Where the Professor goes wrong is that until academic merit and genuine intellectual pursuit return to take their rightful pace, it is nonetheless good to be part of the club and to think otherwise is failing to deal with reality.

I would argue that institutions like Williams, Amherst and Swarthmore which attract talented, diverse and equally intellectually gifted students are the bright lights of undergraduate education. They offer a much more collaborative, personalized and well-rounded educational experience. Often these students choose liberal arts over Ivy league options because they seek a more genuine and fulfilling intellectual experience. Statistics back this up. Top liberal arts college students are shown to study longer hours, participate more often in extracurricular events, have more personal interaction with professors, and report higher degrees of satisfaction in describing their peer interactions. I’d think it be a great service to society if the Supreme Court, the Congress and Wall Street had more graduates from schools like Williams and less well heeled sheep fleecing the public at large.

The true wild card in all of this is the co-mingling of political correctness and mental health — academia is rapidly approaching the old Soviet approach of defining all dissidents as insane and treating them accordingly.

No, no to all, Deresiewicz [nice essay, though] and the others [Goldman cones close to the right answer]. The lack in US higher education is the lack of competition, enforced by the accreditation process, a hoop necessary to jump to get government money. The lives of the youngish may be conditioned by the place where they went to college, but are by no means determined by it. Let anyone who can and wants to pay for an Ivy, or whatever else. Given sufficient competition from below, the best will prevail, on average and over time. There are not now a limited number of seats from which one can learn to succeed and there could be far more seats.

No way will they EVAH make affirmative action class-based instead of race-based. It’s a poorly-kept secret that poor white students outperform poor black students. The top universities will do whatever it takes to keep those black faces in each year’s incoming class. Poor white students (and, incidentally, POOR nonprep black students) will continue to take it on the chin.

As the economic center of gravity shifts south and west, I think there will progressively less business interest in Ivy League pedigrees than before. Harvard probably still has some cache in Dallas, but even that’s dwindling rapidly.