Who gains as Purdue University acquires on-line Kaplan University? For Kaplan, the sale has strong appeal. For-profit companies have been maliciously maligned by politicians and leftist ideologues, and the Obama Administration tried to kill them through regulations that largely did not apply to traditional not-for-profit institutions. Students will like the prestige of the Purdue name, so enrollments will grow, helping Kaplan receive fees from performing non-academic back-office functions.

Shedding the For-Profit Stigma

For Purdue, the deal jumpstarts its comparatively anemic presence in on-line education, buying expertise it simply does not have. It allows it to join the likes of Western Governors University and Southern New Hampshire University, on-line providers that have flourished in part because they don’t have the “for profit” stigma associated with them.

Purdue President Mitch Daniels views this as a natural extension of its land-grant mission, just as agricultural extension services and branch campuses have provided ways for individuals to learn at affordable prices. Daniels, previously a lawyer, budget guru, seasoned business executive, and governor, sees the deal as nearly no-risk for Purdue. Andy Rosen, CEO of Kaplan who, like Daniels, I know and respect greatly, sees this as a winner, as does, no doubt big stockholder Donald Graham.

Yet according to news accounts, the Purdue Faculty Senate said the deal “violated both common sense educational practice and respect for the Purdue faculty….” A long-time nemesis of for-profits and the architect of much of the Obama Administration’s war on them, Robert Shireman, referred to the Kaplan-Purdue deal as “a dangerous long-term marriage between a public university and a firm answerable to Wall Street investors.”

The biggest threat to the deal probably comes not from the faculty, but from the cartel that controls entry into higher education, notably the Higher Learning Commission, Purdue’s regional accreditor. It would not let Grand Canyon convert from for-profit to not-for-profit status, and may do the same to Purdue. The defenders of the status quo (faculty interests, other universities) will try to use accreditation to stop this effort by Purdue to do the equivalent of creating another branch campus. This is another reason why accreditation as we know it should die.

To me, the deal makes a lot of sense. Purdue uses expertise it does not have to expand its educational outreach and improve access. Kaplan probably will gain too, partially just because the word “Purdue” is worth more than the word “Kaplan.” If the new entity is truly part of Purdue, the faculty will ultimately gain some control over curriculum content and teaching. At my school, the main campus faculty has only limited control over those at the branch campuses, and it is not a big issue. I suspect the same will become true at Purdue.

Faculty Want in

What this controversy really is about, however, is ownership. As the late Henry Manne pointed out first over 45 years ago, so-called “not-for-profit” universities like Purdue really generate financial surpluses (“quasi-profits”) that get distributed –much as they do at private corporations. These distributed surpluses are often like dividends.

The problem is the ownership of Purdue, unlike that of private companies, is ambiguous. Legally, probably the state of Indiana owns the institution, and the state turns its ownership interest over to university trustees for administration. Yet the faculty call for “shared governance” is as much a call for “shared ownership.” The faculty thinks, “There would be no Purdue without us —we are entitled to an ownership interest in the enterprise. We want to share in the surpluses.” Yet the Trustees, Mitch Daniels, and Indiana taxpayers may disagree – they are other claimants for at least some ownership rights.

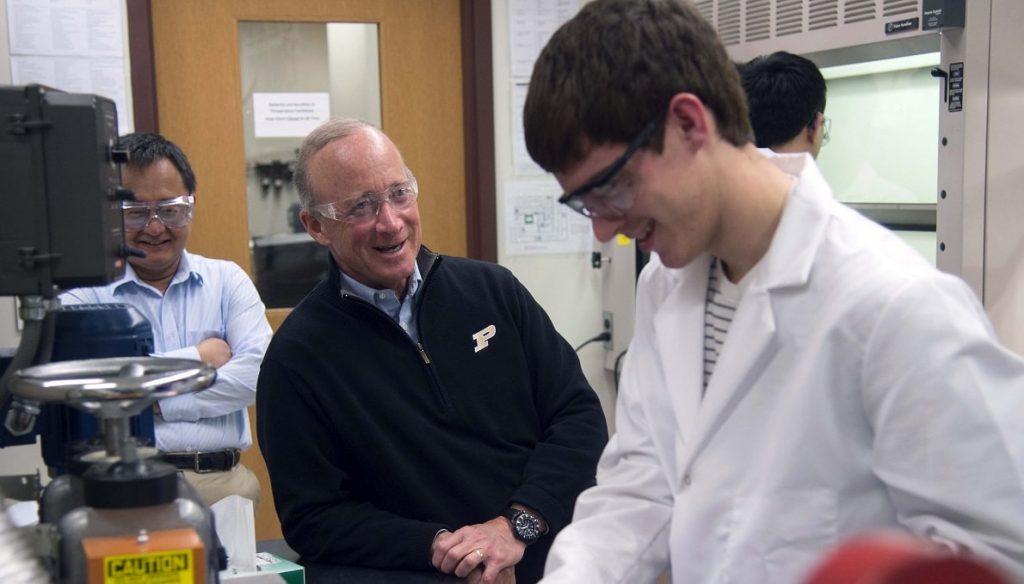

President Daniels has been disruptive of traditional arrangements. He has not raised tuition fees during his tenure. Higher tuition fees are revenues to be distributed, at least in part, as “dividends” to faculty, administrators, and others. He has personally accepted a lower base salary than most university presidents, wanting to be rewarded by bonuses for superior performance. He occasionally sits with students during football games instead of indulging in the perks of the presidential suite. I suspect the students love him –as did the voters who twice elected him governor by solid majorities. He does not bow excessively to collegiate elites.

Too Many Going to College

So, despite having a faculty orientation embedded in my DNA, I am supportive of Daniels move. Higher education is in a bit of a crisis –yet much of it does not know it, being largely shielded by public (state government appropriations, federal student tuition assistance) and private largess (endowments, alumni donations). Enrollments in the aggregate are falling as costs continue to rise and benefits stagnate or even fall.

“Creative destruction” (Joseph Schumpeter) or “disruptive innovation” (Clayton Christensen) are needed to make higher education more nimble, efficient, productive, and responsive to societal needs. Thus, a good case can be made for Daniels’ latest in a long series of innovations that includes the tuition freeze, Income Share Agreements, textbook deals with Amazon, etc.

The strongest case against pushing a big on-line expansion actually is an argument the faculty would emphatically not support: there are simply too many kids going to college, and Daniels’ move is likely to aggravate that problem. The private rate of return on college investments is falling, and the so-called “positive externalities” of higher education are, conservatively put, overstated.

That said, given the policy environment and the attitudes of Americans, higher education, while beset with problems, is not going away soon. Educational entrepreneurs like Mitch Daniels are responding to the changing environment, in the process transforming American higher education. albeit too slowly.