Why Liberalism Failed, by Patrick J. Deneen, uses “liberalism” in the oldest, broadest sense of the term. Deneen’s sweeping, severe assessment of all that has gone wrong in our time attacks modernity’s entire package-deal: individuals possessing inalienable rights; representative, accountable governments that exist to secure those rights; the separation of church and state; the commitment to progress, prosperity, and self-determination.

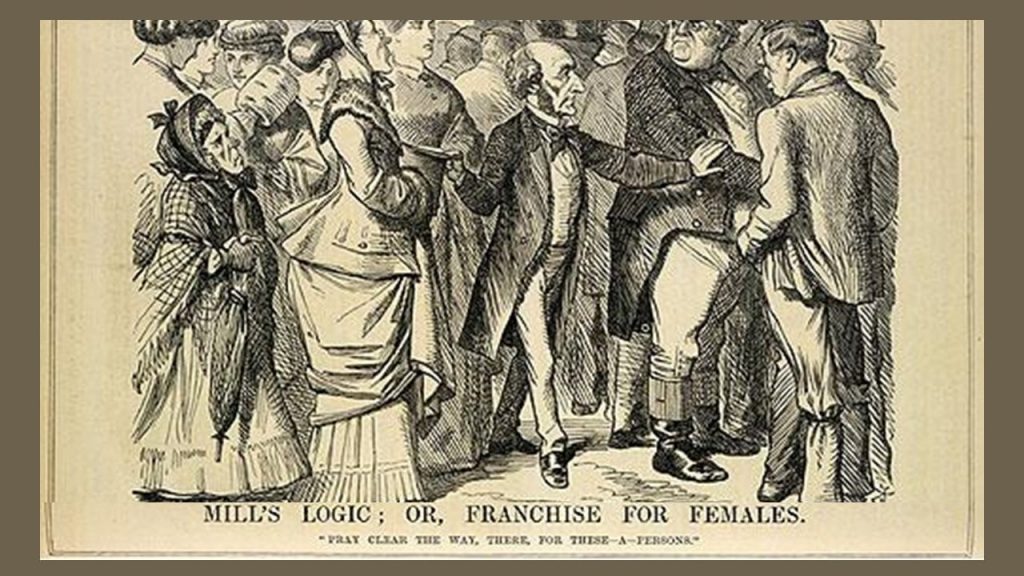

Deneen, a University of Notre Dame political scientist, calls liberalism a “political philosophy conceived some 500 years ago,” a project set in motion by Machiavelli, Francis Bacon, and Thomas Hobbes before John Locke, James Madison, and John Stuart Mill elaborated and systematized it. Though launched with lofty aspirations to promote equity, pluralism, dignity, and liberty, it turns out that liberalism “generates titanic inequality, enforces uniformity and homogeneity, fosters material and spiritual degradation, and undermines freedom.” Liberalism failed because it succeeded, Deneen argues.

Its “inner logic” culminated in crippling contradictions becoming manifest. Communism and fascism, the “visibly authoritarian” ideologies liberalism vanquished, were “crueler,” but less “insidious.” Liberalism’s power to shape our expectations and standards is so great that only as humanity is “burdened by the miseries of its successes” do we begin to realize that “the vehicles of our liberation have become iron cages of our captivity.”

Our existence within those cages is harrowing and false. Democratic politics has become a “Potemkin drama meant to convey the appearance of popular consent for a figure who will exercise incomparable arbitrary powers over domestic policy, international arrangements, and, especially, warmaking.” Purportedly republican governance really consists of “commands and mandates of an executive whose office is achieved by massive influxes of lucre.”

Our existence within those cages is harrowing and false. Democratic politics has become a “Potemkin drama meant to convey the appearance of popular consent for a figure who will exercise incomparable arbitrary powers over domestic policy, international arrangements, and, especially, warmaking.” Purportedly republican governance really consists of “commands and mandates of an executive whose office is achieved by massive influxes of lucre.”

Our economic lives, based on the assumption that “increased purchasing power of cheap goods will compensate for the absence of economic security and the division of the world into generational winners and losers,” are equally fraudulent. And equally malign: “few civilizations appear to have created such a massive apparatus to winnow those who will succeed from those who will fail.” Because of these forces, we are “increasingly separate, autonomous, nonrelational selves replete with rights and defined by our liberty, but insecure, powerless, afraid, and alone.”

That’s one assessment of life in the 21st century. Here’s another:

Many people around the world feel insecure and oppose the spreading of insecurity and war….

The people are protesting the increasing gap between the haves and the have-nots and the rich and poor countries.

The people are disgusted with increasing corruption.

The people of many countries are angry about the attacks on their cultural foundations and the disintegration of families. They are equally dismayed with the fading of care and compassion….

Liberalism and Western style democracy have not been able to help realize the ideals of humanity. Today these two concepts have failed. Those with insight can already hear the sounds of the shattering and fall of the ideology and thoughts of the Liberal democratic systems.

The latter passage does not come from Why Liberalism Failed but appeared instead in an open letter sent to President George W. Bush in 2006 by Iran’s president, Mahmood Ahmadinejad. The striking similarity of the two jeremiads is, at the very least, awkward for Deneen. We know that Ahmadinejad belongs to a broad Islamic movement that, loathing and dreading Western liberalism, wants to extirpate the encroachments it has made in Muslim societies. He offers a critique and a remedy, blood-drenched but nevertheless clear.

There’s no evidence that Deneen favors an American counterpart to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, but also very little evidence about the solution he does endorse. Like most authors of books on politics and social conditions, Deneen is a loquacious pathologist but tongue-tied clinician. Why Liberalism Failed follows the template: half-a-dozen vigorous, detailed chapters that explicate and decry what’s broken, and assign blame for our dilemma, followed by a single concluding chapter—slender, tentative, vague, and unusable—on how to fix the problem.

Given the depths and urgency of the crisis he deplores, Deneen’s reticence about how to find our way out of it is particularly disappointing. At one point he suggests the difficulty of explaining what comes after liberalism is yet another thing to blame on liberalism since its hegemony over our discourse makes it hard to imagine and describe a post-liberal future. At another, he contends that the absence of standards defining that future is a virtue.

Since one of liberalism’s inherent defects is an excessive reliance on political theory, the remedy must be a firm reliance on political practice. More specifically, he endorses “communities of practice,” such as the Amish or those envisioned by Rod Dreher in The Benedict Option. In them, “people of goodwill” can “form distinctive countercultural communities” that create “new and viable cultures, economics grounded in virtuosity within households, and [a] civic polis life.”

Authors can be revealing without being forthcoming, however, and the suggestions Deneen gives about these communities of practice point to larger defects in his argument. His book relates a conversation he had while teaching at Princeton, about the Amish practice of giving young adults a year-long sabbatical from the austere communities where they grew up, so they can sample modern life before deciding whether to eschew it. “Some of my former colleagues took this as a sign that these young people were in fact not ‘choosing’ as free individuals,” he writes. “One said, ‘We will have to consider ways of freeing them.’”

Deneen treats this chilling Rousseauian remark as exposing liberalism’s malevolent essence. It is not one tenured radical, but all of liberalism, that denigrates “family, community, and tradition.” Deneen does not consider the alternative possibility that his colleague was not a representative liberal but a deficient one, severely lacking in the accommodating spirit of live-and-let-live that characterizes liberal societies at their best.

Elsewhere, Deneen anticipates demands for laws to prevent communities of practice from becoming “local autocracies or theocracies.” Such demands, he warns, “have always contributed to the extension of liberal hegemony,” leaving us “more subject to the expansion of both the state and market and less in control of our fate.” This dismissal does not refute a legitimate concern: the people who form distinctive countercultural communities will not necessarily be of goodwill. Nor will the results of their efforts always be “lighthouses and field hospitals” that guide us through the liberal storm and cure us of the liberal sickness. Sometimes they’ll produce Amish communities, but other times they’ll yield Jonestown, Branch Davidians, or the Church of Scientology.

The “most basic and distinctive aspect of liberalism,” Deneen argues, “is to base politics upon the idea of voluntarism—the unfettered and autonomous choice of individuals.” For the time being, while operating in “liberalism’s blighted cultural landscape,” the communities of practice will avail themselves of liberalism’s “choice-based philosophy.” They can invoke voluntarism to resist it, issuing a defiant “Don’t Tread on Me” to liberalism’s encroaching state, market, and “anti-culture.” After liberalism has collapsed under the weight of its contradictions, however, the voluntarist communities of practice might someday produce a “nonvoluntarist cultural landscape.” In it, presumably, individuals will no longer be burdened by the possibility and necessity of making so many choices, including whether to join or leave a community of practice.

These hints that Deneen is something of an anti-anti-theocrat lead us to Why Liberalism Failed’s most serious lacuna: how did a philosophy he portrays as monstrous and anthropologically absurd not only catch on but come to dominate political thought and practice for five centuries? He emphasizes the guile, malevolence, bad faith, and hidden agendas of liberalism’s architects, but doesn’t account for their astounding success in peddling what sounds like a solution in search of a problem.

By way of not explaining what we should do now, Deneen says that we can only go forward, not back to “an idyllic preliberal age” that “never existed.” But an age can be pretty good without being idyllic. Deneen says that none of liberalism’s ideals—liberty, equality, dignity, justice, and constitutionalism—were innovations. All of them were “of ancient pedigree,” carefully elaborated over centuries in classical and Christian philosophy.

Since liberalism brought nothing new to the table, the only reason for its success appears to be that people were fooled into thinking it would hasten the process of making political practice conform more closely to the standards laid out by pre-liberal political theory. Still, why humans made such a big bet on such a bad pony remains a mystery, as does their needing 500 years to start realizing the gamble hasn’t paid off.

One wouldn’t know from Why Liberalism Failed that the dawning of the liberal age coincided with the beginning of savage religious wars that devastated Europe. Over doctrinal differences, Protestants slaughtered Catholics, Catholics slaughtered Protestants, and Protestants slaughtered other Protestants. After two centuries of this madness, people were both exhausted and receptive to the idea that it was more urgent to end than to win the religious warfare.

The liberal philosophy took shape, largely in response to these traumas, and offered a way out of them. Politics would be about some things but not everything, and especially not about God and how to regard Him. Liberalism created a political space in which people would agree to disagree. When first put forward, his approach struck many people as a good idea and continues to appeal today.

Liberalism remains problematic for many reasons, one of them being the difficulty of drawing the boundaries between those things we must agree on, and those where agreement is unnecessary and seeking it dangerous. There are other challenges. Liberalism prevents religion from becoming a threat to civic peace by “privatizing” it, turning it into a kind of hobby. The resulting secularization of the public realm trivializes both public and private life, however, producing what Leo Strauss famously called the “joyless quest for joy.”

Furthermore, and as Deneen makes clear, liberalism draws upon civilizational inventories it does not replenish. Immanuel Kant was wrong: sensible devils cannot sustain a liberal society, no matter how shrewdly ambition is made to counteract ambition. The character of the citizenry is crucial, but the cultural contradiction of liberalism is that the experience of living in a liberal regime turns a great many of its citizens into people lacking the nobility, virtue, and discipline needed to defend and preserve that regime.

It may be, then, that such serious problems mean liberalism is inherently precarious at best and untenable at worst. Nevertheless, liberalism arose in response to the genuine problem of finding a way people of diverse creeds could live together peacefully. Getting rid of liberalism will not get rid of this necessity. Ahmadinejad’s solution is to banish the diversity liberalism presupposes, to hasten the process whereby “the world is gravitating towards faith in the Almighty and justice and the will of God will prevail over all things.”

Deneen’s solution, so far as he has one, sounds like solving diversity by increasing it through an archipelago of micro-polities, different from one another but each committed to its internally unifying vision of the good life. Neither solution sounds plausible or enticing. If, as Deneen contends, we got into our difficulties with liberalism and its attendant difficulties by not asking enough hard questions, there’s no reason to believe we’ll get out of those difficulties without asking hard questions about what comes next, questions for which Why Liberalism Failed offers no answers.

A very good critique to another wise good book. I too found the same weak spots in his book. His articles and speeches up to the publishing of his book provide little imagination to what to do. It is unfortunate that Deneen is favorable to the intellectual swamp known called “Benedict Option”.

We conservatives can do better.