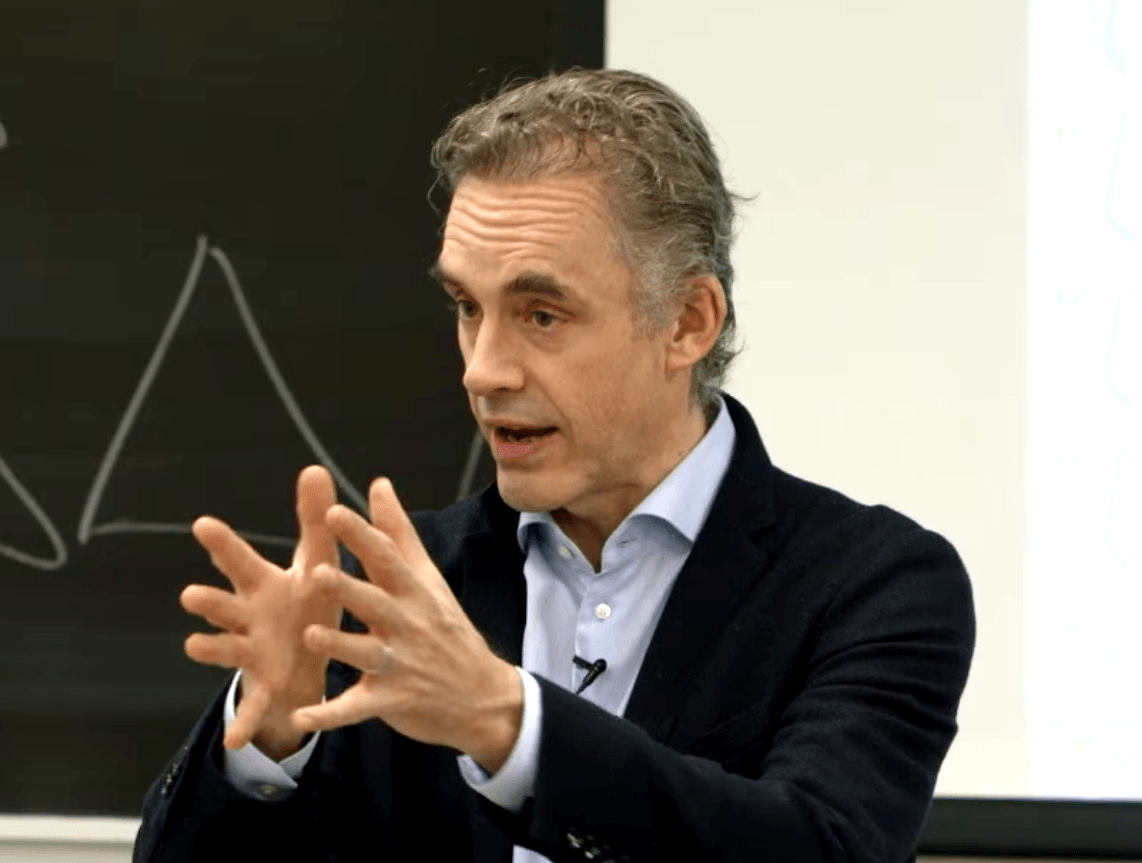

I didn’t really want Jordan Peterson to provide me with 12 Rules for Life. It was enough that Professor Peterson defied the transgender advocates at the University of Toronto who wanted him to adopt nonsense pronouns to address his students. It was heartening to see Professor Peterson stand his ground against that obnoxious guardian of PC verities, Britain’s Channel 4 political correspondent Cathy Newman. But I had no special interest in watching his YouTube lectures and podcasts or plunging into Professor Peterson’s 400-page how-to book (12 Rules) for those suffering the anomie of modern life.

Then along comes Pankaj Mishra in the New York Review of Books to explain the link between “Jordan Peterson & Fascist Mysticism,” and I see no real choice but to pay some attention to the slightly eccentric Canadian defender of English pronouns. Is he the emerging leader of a crypto-fascist cult? Someone leading youth down the path of dangerous lies and illusions? Or is he, as I had supposed, a well-spoken contrarian who has decided to take a personal stand against some of the self-destructive silliness of our age?

I won’t keep you in suspense. Peterson is pretty much who he appears to be to those who have not become unhinged by their hinge-destroying wokeness. That is, Peterson strives to be a gentleman, but one who has honed some sharp opinions about feminism, social justice warriors, and attempts to put progressive ideology in the center of domestic life. These things mark Peterson as an enemy to Pankaj Mishra, an Indian essayist and novelist, who has something of a side-specialty in penning diatribes against Western scholars who do not come up to his standards.

In 2011, Mishra attacked the British historian and Harvard professor Niall Ferguson for his book Civilization: The West and the Rest, accusing Ferguson of racism. Ferguson responded in strong words, quoted in The Guardian, describing Mishra’s critique as “a crude attempt at character assassination” that “mendaciously misrepresents my work but also strongly implies that I am a racist.” He called Mishra’s article “libelous and dishonest.”

Mishra likewise went after the distinguished British journalist Douglas Murray in a New York Times review of Murray’s book, The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam. He characterizes Murray’s book as “a handy digest of far-right clichés,” “fundamentally incoherent,” and marked by “retro claims of ethnic-religious community, and fears of contamination”—all without any attention to what Murray truly says. Mishra goes out of his way to continue his attack on Murray in his essay on Peterson, linking the two as members of the “far right sect” that idolizes Solzhenitsyn and deplores “the attraction of the young to Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.” The “sect” appears to consist of everyone who has doubts about the left’s current conception of “egalitarianism.”

Mishra no doubt pleased his readership at the London Review of Books and The New York Times with his attempted take-downs of Ferguson and Murray, and I expect no less from the readers of the New York Review of Books in the case of Peterson. The left is perpetually hungry for figures it can demonize. It can gorge on its hatred of Trump but still feel an appetite to devour some other prey. Mishra’s article is an attempt to supply a recipe. Peterson is staked out mainly because he has become so popular, or, as Mishra puts it, Peterson’s “intellectual populism has risen with stunning velocity; and it is boosted, like the political populisms of our time, by predominantly male and frenzied followers.”

So, part of the problem with Peterson is that he attracts those frenzied deplorables. What does Peterson really have to offer in 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos?

You arrogant, racist son of a bitch Pankaj Mishra: How dare you accuse me of “harmlessly romancing the noble savage.” That’s how you refer to my friend Charles Joseph (https://t.co/uF5XV2DVXx), who I’ve worked with for 15 years? https://t.co/s8fqE1M7D7

— Jordan B Peterson (@jordanbpeterson) March 20, 2018

No, Not Mysticism

Peterson is a clinical psychologist who has wide-ranging interests in mythology, literature, religion, and philosophy. When Mishra jabs at him for “mysticism,” he goes wide of the mark. Peterson is a rationalist attempting to find a core of meaning in the world’s diverse myths and religions. When Mishra doubles up with the charge of “fascist mysticism,” he is apparently extrapolating from Peterson’s adoption of Martin Heidegger’s use of the term Being (“with a capital B”). Heidegger was one of the 20th century’s most important philosophers, but he infamously threw in his lot with the Nazis, and he is not everyone’s bottle of schnapps. Not mine at any rate. Still, Being “with a capital B” is a long-established philosophical term, and Peterson provides a layman’s definition at the outset. “Being” is “the totality of human experience,” in contrast to objective reality. It is “what each of us experiences, subjectively, personally and individually, as well as what we each experience jointly with others.”

That’s as technical as Peterson ever gets, and it is neither mystical nor fascist. The rest of the book consists of happily phrased bits of advice (the “12 rules”) that are really occasions for discursive essays that weave together humor, science, and common sense. The literary tradition that Peterson belongs to is that of 18th century English essayists such as Addison and Steele in The Spectator and Samuel Johnson in The Rambler. Those writers could be framed as “intellectual populists” too since their goal was to uplift the growing middle class through palatable moral instruction. Different times call for different tones, but it would not be far from the mark to say that Jordan Peterson is the Joseph Addison of the 21st century.

No Slouching, Shoulders Back

Rule 1: “Stand up straight with your shoulders back.” I’ve heard this often enough from my gym trainer to wonder whether he should get a cut of Peterson’s royalties. But, no. Along with most people, I heard it through childhood. It is age-old wisdom. I know of no culture where children are taught, “Slouch when you stand, and hunch your shoulders.” So, Peterson starts on firm ground. His first rule isn’t just for desk-bound Americans or slouchy teenagers. It has common humanity written into it, or, if you will, Being.

But it is less the rule than the essay written around the rule that counts. In this case, Peterson begins by comparing the territoriality of lobsters and house wrens, thus establishing that the animals that are wired to defend themselves range from the ocean bottom to the air. We then learn a bit about the dire consequences to a lobster that loses its fight for its territory. (Its brain shrinks.) This leads to some comments on neurochemistry and an observation on the “unequal distribution” of “creative production. Most scientific papers are published by a handful of scientists. Only a relative few musicians produce most of the recorded music, etc. Once dominance is established, the winner usually prevails without a fight. All the victorious lobster needs do is “wiggle his antennae in a threatening manner.”

This takes us but a few pages into the world of Rule 1, but the reader by this point can foresee the destination. Standing up straight with your shoulders back is the way human beings signal confidence and mastery of the situation. We are men, not lobsters, but we are all part of a biological order that follows the same basic rules. “Walk tall and gaze forthrightly ahead,” says Peterson, and good things will happen. People will assume “you are competent and able.” You will be “less anxious.” “Your conversations will flow better.” And “you may choose to embrace Being, and work for its furtherance and improvement.” And after that, “you may be able to accept the terrible burden of the World [with a capital W] and find joy.”

The whole essay flows smoothly with Peterson’s lightly-worn erudition until it hits the curb at the very end with that joyful embrace of Being. Some readers no doubt will find it gives a little spring to their intellectual step—a sense that we have transcended the order of Crustacea and are now in the sad but ennobling predicament of humanity. I don’t mind so much Peterson’s efforts to elevate the prospect, but his stepping stool of Heidegger’s jargon is intrusive.

But does it make Peterson a fascist mystic? No, it makes him, like most scholars, someone who indulges some of his whims.

Hierarchies Found in Nature

In his explanation of why Peterson is so bad, Mishra touches on Peterson’s universalism. Peterson, he says, “insists that gender and class hierarchies are ordained by nature and validated by science.” This is a serious distortion of Peterson’s point. Peterson, it can be fairly said, argues that the principle of hierarchy can be found in nature and that humans are not at all exempt from that principle. But that is a very long way from saying that Peterson validates “gender and class hierarchies” in general. He does nothing of the kind.

Mishra speculates that “reactionary white men will surely be thrilled by Peterson’s loathing for ‘social justice warriors.’” And he proposes that “those embattled against political correctness on university campuses will heartily endorse Peterson’s claims” that whole academic disciplines are hostile to men. Well, now that you mention it Pankaj, the latter statement seems securely grounded in the facts. But isn’t it a bit odd to attack a book and an author by speculating on the sorts of readers the book may attract? For what it is worth, I suspect the core audience for 12 Rules for Life includes plenty of young women as well as young men, launched into adult life from colleges and universities that have given them no serious moral preparation at all—only a basketful of social justice slogans and anti-Western attitudes.

David Brooks extolled Peterson’s book in The New York Times but, like Mishra, takes the book as mainly directed to young men for whom it counsels, “discipline, courage and self-sacrifice.” Oddly, it is only young women reading it on the subway. Perhaps they are looking for those disciplined, courageous, and self-sacrificing young men, who are now so conspicuous by their rarity.

Peterson is stepping into that space with a non-sectarian message that respects the multicultural sensibilities of the young. He is for sure grounded in Western thought and literature but is ready at any moment to draw on non-Western cultures and traditions. This isn’t always to elevate those cultures. When he writes about Western homicide rates, he compares them to the !Kung bushmen, dubbed by anthropologists “the harmless people,” whose annual homicide rate is eight times that of the United States. Of course, the Kalahari !Kung are pretty peaceful compared to other primitive peoples.

At Least Don’t Lie

It seems a bit unfair to Peterson to divulge all twelve of his rules, though they are freely available on the Internet. Moreover, the rules themselves are not the heart of the book. What he builds around the rules is what counts. But for the flavor of the thing, here are a few of Peterson’s aperçus:

Rule 2. “Treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping.”

Rule 5. “Do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them.”

Rule 8. “Tell the truth—or, at least, don’t lie.”

Rule 9. “Assume the person you are listening to might know something you don’t.”

They just don’t make fascist mystics the way they used to.

Either that or the vitriol of reviewers for progressive journals is reaching new concentrations. Essays such as Pankaj Mishra’s “Jordan Peterson & Fascist Mysticism” seem designed to give permission to liberals to sneer at writers whom they have never read. An Indian intellectual says that so-and-so is a racist, an ethno-nationalist, a fascist, a mystic. You are therefore on good ground to ignore so-and-so, and if his name comes up in conversation, you know exactly which epithet to apply.

Peterson, as far as I can see, deserves his popular success. He is a morally serious, highly literate writer who has important things to say. He says them rather well in an entertaining manner that doesn’t compromise either his clarity or his essential points. 12 Rules for Life isn’t faultless. Peterson sometimes wanders too far afield, and his forty-some mentions of Being is about 39 too many. But for readers trying to find their way through the “chaos” of contemporary North American cultural decline, these “rules” are a good place to begin. If you don’t like all of them, that’s fine. Peterson will at least make you think about why you don’t like them, and perhaps you will find your way to a better distillation of wisdom. But you probably won’t find a better Virgil to take you safely step by step through today’s Inferno.

“They just don’t make fascist mystics the way they used to.”

Ouch!

I’m a 71 year old classical liberal, middle class, science-oriented, agnostic, retired-white collar male. I don’t need Peterson as a mentor, though I find him immensely refreshing. My interest is whether there is societal value in his message for my grandchildren. I think there is. I really, really hope there is.

I have so far watched over 100 hours of Peterson’s UoT lectures, interviews, commentary, and speeches. I’ve read _12 Rules_. I’m reading _Maps of Meaning_. I’ve read several of his research papers.

My impression is that he is intelligent, articulate, polymathic, grounded, kind, thoughtful, and humbly aware of his own exhaustively examined faults.

I recognize my predisposition to accept Peterson’s message. My sympathy could be a terrible mistake if I’m wrong. So I avidly read his critics.

I read Mishra. Let’s just say he did not convince me I am wrong about JBP. He did further persuade me that Peterson drives postmodernist bigots into irrational apoplexy.

I tend to post commentary on the Peterson related articles I read when they are intellectually honest. Especially the critical ones. In Mishra’s case this proved impossible. He’s a poor writer and a fatally biased thinker whose arguments depend on misdirection, misrepresentation, and ad-homininism. I don’t have the time or tolerance to go fisking in that particular swamp.

Thanks for this fine article. I’ll be re-reading it.

Not only does JP acknowledge that he is probably wrong in all sorts of ways, but encourages his audience to pick and find fault in his world view.

To pull apart is arguments and find where he’s wrong.

Even in reference to his books he makes no claim to being a faultless author and admits his writing style is hard to get into and follow at times.

I find this attitude commendable and none too common today.