The right to breathe is not generally understood as the right to choke others. The right to move freely is not widely understood as the right to slip into your neighbor’s house in the middle of the night unannounced. The right to listen to Neil Diamond’s greatest hits is not universally interpreted as the right to make other people listen to “Sweet Caroline.”

And yet these days more than a few people have decided that “academic freedom” guarantees your right to silence other people who are attempting to express views you disagree with.

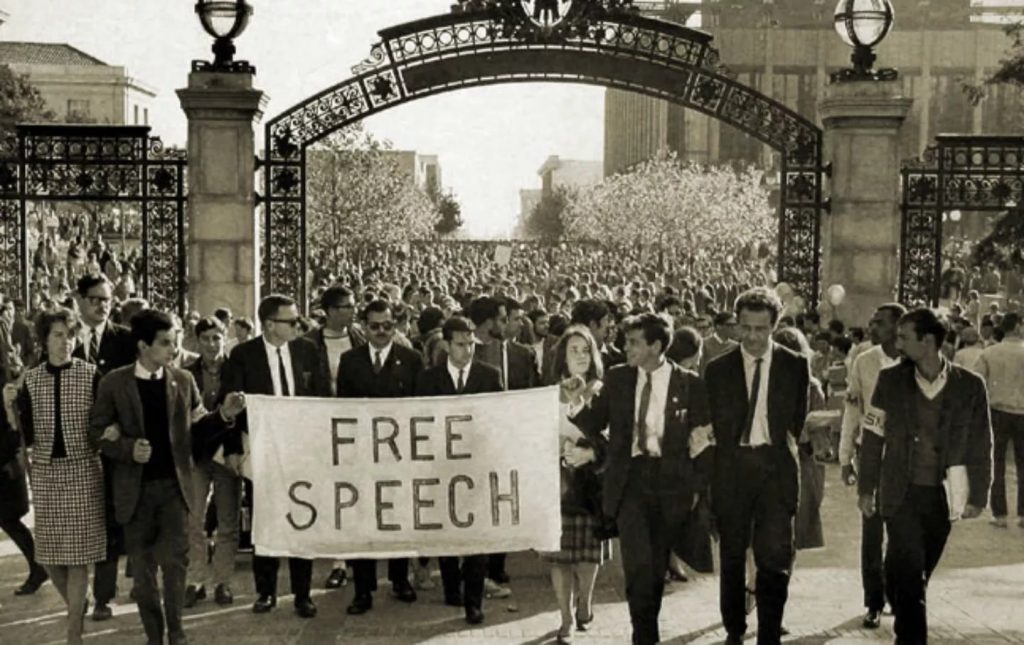

This sounds like a joke, but it has been put forward in earnest by many student protesters in the last few years. I first heard the “I’m-exercising-my-academic-freedom-to-shut-you-up” rationale in connection with the Black Lives Matter protesters who invaded the Berry-Baker Library at Dartmouth in November 2015. But it has since become the common currency of lawless protesters, whether at Berkeley, Middlebury, or Claremont-McKenna.

Perhaps the open letter from Pomona College students to President David Oxtoby demanding that he “take action against the Claremont Independent editorial staff for its continual perpetuation of hate speech, anti-Blackness, and intimidation toward students of marginalized backgrounds,” is the perfection of this conceit. The Pomona students decided that “free speech” has become “a toll appropriated by hegemonic institutions.”

Campus Life Not Like a Baseball Game

Actually, on that last point, they are right. Colleges and universities are “hegemonic institutions.” I don’t know if those students understand their own catchphrases, but translated into plain English, this simply means that colleges impose broad control over their community of faculty members and students. They have rules above and beyond the rules of the surrounding society. If you go to a baseball game, you are free to boo the other team and scream at the umpire if you think he made a bad call. On campus—at least in principle—you must listen quietly when someone argues a point you disagree with, and if the moderator in a debate makes what you think is a bad call, your only legitimate option is to explain why you think it is wrong.

Those rules are part of what we mean by “academic freedom.” Clearly, academic freedom is not the natural way people behave towards each other. It is an artificial thing, a “social construct,” as we say these days. And because it is artificial, it only works in special circumstances where people agree to forego their right to boo the other team, shout imprecations at the umpire, or move beyond words to the kind of hard buffets that put professors of political science in the hospital.

Three cheers for institutional hegemony, without which no would have academic freedom. “Good times never seemed so good,” Sweet Caroline.

But how is it that good old Hegemony U has found itself so incompetent in upholding its most basic rules of the road? Observers have offered some pretty persuasive answers to why Middlebury President Laurie Patton has been so feckless; why UC Berkley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks displayed the steadfastness of a saloon door; and why Claremont McKenna President Hiram Chodosh has risen to the occasion with the moral dignity of a fidget spinner.

The answers include the continuing descent into postmodern insouciance, where no encompassing principle presides; the swarming animosities of identity politics, which have stung all the beekeepers into submission; and the progressive left’s willingness to kick away the ladder of free speech by which it climbed to dominance, lest anyone else try that ascent.

Up for Grabs for a Century

I have one small addendum to that list of explanations for why our defenders of academic freedom went out to lunch and never came back. I suspect that some of them got confused by the menu. “Academic freedom,” an artificial thing, a “social construct,” isn’t amenable to scientific precision. It isn’t Mars or Jupiter, sitting in the heavens as a definite planet. It is more like Pluto or one those other trans-Neptunian objects with strange names, such as the dwarf planet Haumea: detectable but not settled into any plain definition.

Because “academic freedom” isn’t any one, definite thing, it has been up for grabs for over a century. The grabbing began in 1915, when the newly formed American Association of University Professors offered its “Statement of Principles,” that in twenty-some pages of stately syntax and high-minded declaration laid out a commanding vision of the intellectual rights of America’s university faculty. The 1915 AAUP statement didn’t settle anything. For the next 25 years, the AAUP and college presidents went on wrangling, with numerous summits and unsatisfactory attempts to reach

For the next 25 years, the AAUP and college presidents went on wrangling, with numerous summits and unsatisfactory attempts to reach an agreement. In 1940, they did, at last, reach an agreement of sorts and issued a much shorter and—in many ways—less satisfactory statement. The 1940 AAUP Statement remains in force at the vast majority of American colleges and universities as their basic position on academic freedom. But having discovered the fluidity of the idea, the academic world could not stop with just two statements.

There are in fact now many thousands of statements, interpretations, codicils, redactions, and expostulations about academic freedom. The World Catalog lists nearly 100,000 books on the topic. “Look at the night and it don’t seem so lonely,” Sweet Caroline.

My colleague David Randall and I have undertaken the task of providing a little bit of order to this chaos. We have just posted a chart that offers an easy comparison of what we take to be the top ten authoritative treatments of academic freedom. It gives the reader the opportunity to see at a glance which definitions are rooted in the pursuit of truth, which ones connect tenure, and which ones call for sanctions against violators, and so on through 25 categories. It is a work in progress if we are still allowed to talk about progress in the post-modern anti-hegemonic hegemony.

I offer this in part as a service to Presidents Paton and Chodosh and Chancellor Dirks. They can now pick the definition that best lends itself to doing nothing while their students riot, or imposing “sanctions” on violators that have the permanence of a Snapchat message. “Charting Academic Freedom: 102 Years of Debate” may also, however, prove to be of some value to others who have found little clarity in the swirl of conflicting claims about academic freedom.

Explore, and find the most compelling definition and sing in your best imitation of Neil Diamond, “How can I hurt when I’m holding you,” Sweet Caroline. Well, you can and will, but you will still be better off knowing that some definitions of academic freedom are a lot better than others, at least if you care about creating a civilized place for learning.

Printed with permission from the National Association of Scholars