The year is 1901, and the British Empire rules the waves. The small island nation’s maritime empire crisscrosses the globe, governing over twenty-five percent of the world’s population.

As a blue power, Britain’s national strategy is to protect its trade networks, ensure freedom of navigation for its merchants, maintain the balance of power in Europe, and avoid being drawn into a war on the continent.

Yet, while seemingly at its peak, Britain faces threats from all quarters.

Russia is encroaching on China to the East, while Germany is building a naval fleet set to challenge English maritime hegemony. War is raging in South Africa, India is seeking independence, and the Boxer Rebellion is in full swing. Queen Victoria—the period’s namesake—has passed away, and Theodore Roosevelt is now President, leading an increasingly powerful and industrialized nation following the assassination of William McKinley.

In short, the world is on fire.

Thus, Great Britain made two strategic calculations, thereby ending Britain’s period of Splendid Isolation.

The first was to protect its interests in East Asia from Russian incursions to the East. Therefore, England signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance at Lansdown House in London in 1902, an agreement designed to align strategic interests with a rising Japan, a nation that was becoming increasingly modernized during the Meiji Era.

The second calculation was to ensure Britain’s interests were protected in the Western Hemisphere; so, Great Britain signed the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty of 1901 with the United States.

The treaty permitted the United States to build and control an isthmian canal across Central America. This canal was the Panama Canal, completed in 1914. It cut eight thousand miles off the transit around the horn of South America to the lucrative markets of the Orient. The canal was completed in the nick of time, for one month earlier, Europe had plunged into the cataclysm of the First World War.

Fast-forward to 2025, Donald J. Trump is President of the United States, and the U.S. rules the waves.

The Global South is aligning to challenge the American International System, the Middle East is in turmoil, Russia is menacing the marchlands of Europe, and China is rapidly militarizing its hard power and technological prowess to rival the U.S.. The Panama Canal, a critical choke point upon which over forty percent of America’s trade is reliant, is under indirect Chinese control, an extension of the Communist Party’s subversive Unrestricted Warfare Campaign against the U.S..

As the predominant hegemon on the world stage, the U.S. has four main tasks: to protect the freedom of navigation in the world’s oceans, to provide a security blanket for Europe, to ensure that domestic trade and manufacturing remain strong and secure, and to maintain a stable financial system for global markets.

In a recent address to Congress, President Trump stated, “[Months ago,] I stood at the dome of this Capitol and proclaimed the dawn of the golden age of America … to further enhance our national security, my administration will be reclaiming the Panama Canal, and we’ve already started doing it.”

After a seventy-five-year period of Pax Americana, geopolitics has returned, and it has returned with a vengeance. Strategic ports, rails, and transit routes, as well as fiber-optic cables and satellite systems, are now under threat from peer adversaries on the global stage.

Yet, in many ways, this is nothing new. In fact, it is simply a return to what has been the normal course of affairs for centuries—it is geopolitics 2.0. In effect, the past seventy-five years have been an exception rather than the rule.

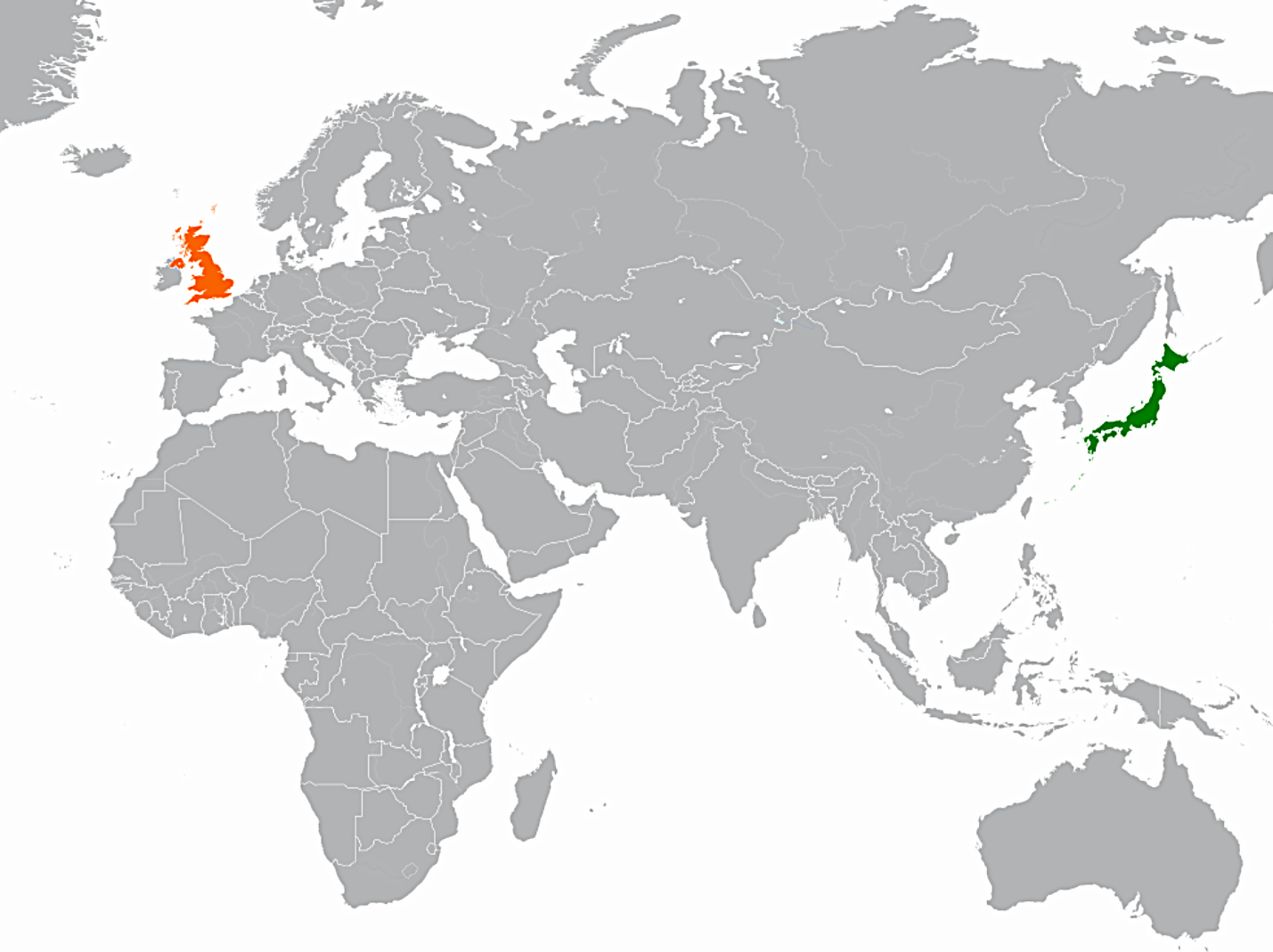

Much like Greenland and Alaska protect the Circular Route and serve as forward bases for missile defense and critical resources, England and Japan serve as checks against expansion from the Eurasian landmass on both the Atlantic and Pacific, respectively.

England guards the Baltic’s choke point, containing the Russians, while Japan serves as an unsinkable aircraft carrier in the South China Sea, holding China in check.

[RELATED: Higher Ed Can Support U.S. Reindustrialization]

Thus, the U.S. must make two critical decisions.

The first must be to reclaim and harden the Panama Canal by any means necessary. It must, in effect, enact a new Monroe Doctrine for the multi-polar age, effectively removing any peer rival’s influence from the Caribbean to the Arctic. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy both took a similar view when challenged by peer rivals, and so too should President Trump.

Secondly, the U.S. must enter new economic, financial, trade, and technology agreements with Japan and Great Britain.

While there may be much pomp in America about creating a new STEM and artificial intelligence (AI) workforce in the higher education sector, one should ask what the circumstances are.

Currently, over fifty percent of graduate STEM students in the United States are foreign-born, as are over fifty percent of the AI workforce in California. This should give one pause for thought.

This writer would contend that international undergraduate students provide a net boon for the American higher education system. Indeed, they provide cultural exchange, increase revenue generation from higher tuition fees, and return home having been educated with American liberal value systems that promote democratic and humanistic ideals. However, it is a high-risk venture to suggest that hosting international graduate students in the STEM fields who originate from peer rival adversaries is a wise idea.

The majority of these foreign-born graduate-level STEM students and workers are from India and China—the IC circuit, as it is colloquially known in Silicon Valley. The IC circuit has essentially monopolized the graduate STEM fields, thereby reducing international diversity and limiting opportunities for international students from less developed nations.

It makes zero national policy sense to educate and employ peer rival competitors who will, in most likelihood, return to their home nations to aid in national research and development goals with the explicit target of weakening the Americanist-based system.

Graduate STEM students from China and India should be phased out upon matriculation, with domestic students as well as those recruited from allied nations filling their places. Japan and Great Britain provide the answer, as these two nations are highly developed, well-educated, and strategically aligned with American business, defense, and technology sectors.

While Britain’s financial district, known as the “square mile,” still possesses the highest concentration of wealth in the world—a relic of the days of Empire—its citizens live in economic poverty equivalent to the lowest-performing state in America—Mississippi. Japan, too, is suffering from a culture of contrition established following the Second World War and is dependent upon ninety-seven percent of its energy needs from imports. America can help.

Freshly inked educational, corporate, and governmental partnerships with strategic depth would lift Japan from its lost decades of economic stagnation, provide secure energy supplies, and reinvigorate an ailing Britain, whose manufacturing and industry have suffered under decades of globalist-oriented policies.

[RELATED: The UC System Is Risking National Security with China—It Must Cut Ties]

Japan will provide a steady stream of finance and tech talent, while England will offer a well-educated and highly skilled manufacturing workforce in industries such as shipbuilding and multi-modal port construction. President Trump’s recent Executive Order to rebuild America’s maritime industrial base while “expanding and strengthening recruitment and training” lends credence to this policy.

Along with increased federal funding and the best and brightest from our archipelagic allies to the East and West, a new cadre of international students will create an asset and not a liability for American national security interests.

Combined with newly implemented and federally supported American-based higher education STEM and vocational programs that work in cooperation with domestic firms, access and opportunity will return to American citizens while strengthening Japan’s and England’s technology and industrial sectors. This is a sound policy for America.

It is the hard reality of Great Power competition that the U.S. will not accept a peer, and that our rivals will not accept a superior.

Thus, in these straitened times, the U.S. should take a page from history and strengthen America’s two loyal wingmen whose national security interests align with those of the U.S. This will ensure a check on Chinese and Russian expansion into the Western Hemisphere and protect the path between the seas.

Image: “Map indicating locations of Japan and United Kingdom” by Hogweard on Wikipedia

So this guy wants to abandon Chinese and Indian — Indian! — STEM students. From countries with 2.8 billion people? And compensate with students from Japan and the UK — with maybe 7% of the population. I see a possible problem with this idea. I see another problem with the Japanese and UK students. Namely, they are already heavily subscribed to American universities.

This is really a totally reactionary, retrogressive plan. (Acutally, I do see some problems with the the Chinese. First of all, we may get into a war with them soon.)

America is rapidly destroying its desirability as a destination for the best scientists in the world. It seems that so-called “MAGA Trump” types have a death wish for the country.