Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the soon-to-be-published National Association of Scholars report, Rescuing Science. It has been edited to align with Minding the Campus’s style guidelines and is cross-posted here with permission.

I sought a career in academia because it promised a life of intellectual freedom; to think, write, and teach what I wanted; to follow interesting questions without regard to where they took me. Mostly, my academic career delivered on that promise. There were tradeoffs to be made, obviously. For all the wonderful privileges of the academic life, academics are generally not well-paid, certainly not in comparison to other professionals whose training and preparation are as rigorous and demanding as a scientist’s. But I was fine with that. The intellectual freedom I gained was an ample return, and I like to think I held up my end of the bargain.

In recent years, the attractions of the academic life have been slowly but relentlessly falling away. Tenure is on its way out. Freedom of inquiry is increasingly constrained. Pushy administrators presume to dictate hiring, promotion, and curricular decisions that should sit squarely in scientists’ hands. “We can’t hire a white guy.” Faculty governance has become mostly performative. Academic scientists—indeed academics generally—once the raison d’etre of the university, increasingly find themselves reduced to being mere employees of the administrations that employ them, with no more protection or intellectual freedom than the custodian that mops the halls. Scientists have become serfs to the institutions that employ them.

This raises the uncomfortable question: are the universities still scientists’ natural home? For much of the 20th century, they were. Even so, robust science has always existed outside the academy. So the question again: Which is the best place for science to flourish: in, or out? In 2011, President of the National Association of Scholars Peter Wood put the question succinctly: universities need scientists more than scientists need universities. So, why stay? The question comes more into focus when universities are increasingly looking at scientists not as intellectual adventurers but as exploitable revenue generators.

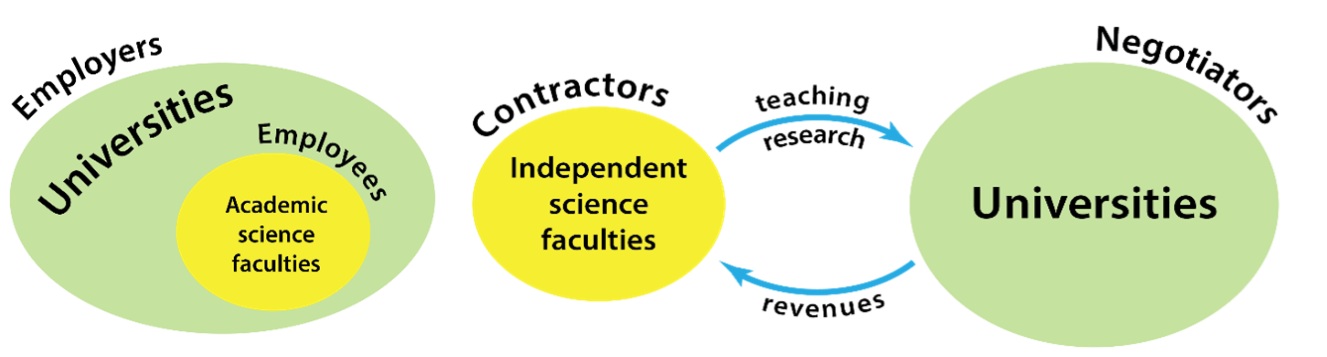

Most scientists’ instincts are to stay and reform their institutions from within. If universities have lost their way, it’s the academics’ duty to guide them back. It’s an admirable instinct, to be sure, but unlikely to succeed, because universities have little interest in defending values that scientists hold dear. Scientists want freedom of thought, but that doesn’t pay. Universities want things that pay, and their funders—mostly the government—provide the funds. In the end, scientists’ intellectual freedom will always come up the loser, because it is only universities that have the power to advance their interests. Scientists have become academic serfs, in other words, and their serfdom will continue as long as the power imbalance continues (Figure 1).

In the American university, scientific serfdom is perpetuated by a hierarchy of power that is embodied in the university’s organizational tree. A university is an assemblage of colleges. Each college has its own leadership structure of provosts, deans, and faculty. The colleges are not autonomous, however, but are subordinate to the university’s administration. The administration leads, and the colleges fall into line with whatever the university leadership wants.

Contrast this with the organization of English universities like Cambridge or Oxford (“Oxbridge”). There, colleges are independent corporations that own and control their own facilities, endowments, and administration, set their own curricula and standards, and hire and promote faculty. If the university administration wants the colleges to do something, it has to persuade them, not command them.

The Oxbridge system is not perfect, certainly, but academics there at least are not serfs. What if American universities could adopt an Oxbridge-style organization and so restore a degree of autonomy to the scientists and scholars employed there? That’s likely a bridge too far for American universities, which would have to give up the power and control they now have. Nobody gives up power voluntarily.

[RELATED: $15 Billion Saved from Indirect Costs Boosts Research]

You wishful reformers from within, take note. It has been tried before, in the 1960s when the University of California (UC) established a new campus at Santa Cruz. Full disclosure: I earned my BA at UCSC, College VIII, ’76. UC Santa Cruz was envisioned as a group of small, semi-autonomous residential colleges, modeled explicitly on the Oxbridge system. The “field of dreams” that was UC Santa Cruz’s initial vision failed to materialize, however, foundering ultimately on a combination of student demographics, class resentment, and institutional rivalries. A sheep does not last long in a herd of wolves.

If the university cannot be trusted to reform from within, what then? One alternative will be control imposed from without. This is what we are witnessing now, and it’s fair to say academics are not happy with it. Even though I think universities need to reform, and they won’t do it on their own, I agree with my unhappy colleagues that government intervention compromises intellectual autonomy.

That leaves only one alternative: scientists should leave the university and build institutions that can guarantee their autonomy. Fortunately, a promising model already exists for our hypothetical scientist emigrés to follow. They can take a leaf from other professionals, like attorneys or physicians, and organize into autonomous professional associations, where scientists, not administrations, are in control.

Figure 1. Shifting the professional relationship between academic scientists and universities. Left: Academic scientists as university employees. Right: Academic scientists as contractors to universities for teaching and research.

Let us call these Independent Science Faculties (ISF) (Figure 1). In an ISF, scientists would no longer be subordinate employees of universities. They would, rather, act as contractors to provide teaching and research services to a university, for which the ISF would be paid. Scientists in an ISF could still teach, do research, and train graduate students, all the things academics now do, but with a crucial difference: scientists in an ISF would be contractors, not employees, which would put them on a more equal footing with their university. As I put it in a 2023 Minding the Campus article:

Suppose, for example, that … administrators had taken it into their collective heads to impose an ideology that its science faculty found inimical. As … faculty (employees, to be frank), they would have had little choice but to knuckle under.

But what if the professional arrangement was different? Again, to quote myself:

Imagine that a group of academic biologists working at (for the sake of argument) Simplicio University (SU) decide to leave and organize themselves into an ISF firm (for the sake of argument), Salviati Life Sciences, LLC (SLS). SU now faces a choice. It could hire, at great expense and disruption to its mission, an entire new life sciences faculty. Or it could enter into a contract with SLS to provide the educational and research services its formerly on-board biologists had provided. SU could continue to offer its students a biology curriculum, and SLS could deliver the top-notch education its members had always provided.

If scientists were to emulate lawyers, would they then be thrust into the grubby world of ambulance chasers we see advertised so aggressively on television? Actually, professors would likely find an ISF a congenial home. Law firms organize themselves into hierarchies of rank, like academic departments do. At the top are senior partners (≡ professors), followed by partners (≡ associate professors), then junior partners (≡ assistant professors), along with a host of interns and paralegals (≡ graduate students, post-docs, volunteer undergraduates). Like professors on the path to tenure, partners in law firms advance through ranks via rigorous procedures of development and evaluation. In an ISF, decisions on recruitment, promotion, and advancement would sit squarely in the hands of the firm partners, in contrast to the ideological commissars who serve at their administration’s pleasure and have the power to impose their will on faculties. In short, scientists in an ISF would be back in charge of their professional lives.

What of that bulwark of intellectual freedom, tenure? Professional firms actually have a kind of tenure system, the principal difference being how a tenured position is secured. In a university, tenure is an increasingly flimsy and frayed promise: ask Amy Wax, or Scott Gerber, or dozens of other professors supposedly protected by tenure. If a university wishes to push out a tenured professor, it can do so, and will almost always win, because the outcome turns not on who is morally right, but on who outlawyers whom, and a university’s pockets are always deeper than the target’s. And there are armies of disposable adjuncts always standing at the ready.

An ISF is a way for scientists to retain power in a world where adjunct status is becoming the norm. In a law firm, a partner’s security rests on having an equity stake in the firm. This offers better protection and more freedom to partners than tenure does for professors. If a law firm wishes to push out a troublesome partner, for example, it must buy out the partner’s equity share, and the buyout will come out of the pockets of the firm’s other partners. This tends to sober everyone up: a Captain Ahab will not long be tolerated when his obsession starts pilfering money from the other partners’ pocketbooks.

And whence would come the funds to secure equity stakes in an ISF? Revenues from universities for teaching and research services have already been mentioned. Research grants are as available to private entities as they are to universities. In an ISF, the grant money wouldn’t first make an expensive diversion into the coffers of a bloated administration. ISFs could set overhead rates as they saw fit, set up their own bonus and incentive structures, look for economies that university administrations seem incapable of doing. ISFs could also tap private donors for support, as is commonly done throughout the 401 (c)(3) space right now. In this, ISFs would be building on an already successful model for independent research institutes, like the Whitehead Institute, the Keck Foundation, or the Breakthrough Institute.

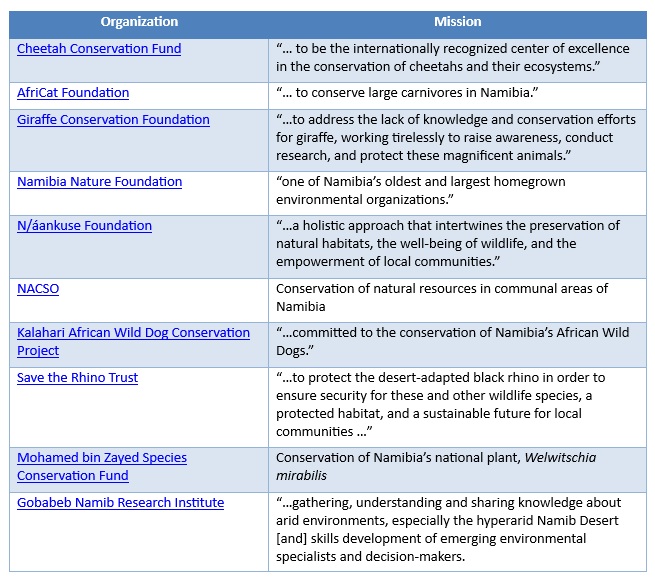

The major difference an ISF would bring to this model would expand the mission scope to include teaching. Again, there are successful models that ISFs could follow. I am most familiar with the research landscape for conservation biology in the developing country of Namibia, where I have spent considerable time for my own research. For many years following its independence in 1990, Namibia did not have a national research program, and one is only now getting off the ground. Even so, there has long been a vigorous community of conservation biology researchers in Namibia, largely working through a number of private research institutes and civil initiatives that support their activities through grants, contracts, donations, and other streams of revenue (Table 1). In addition to their research work, these independent institutes have cooperative ties with Namibia’s two universities, providing formal coursework, hosting capstone experiences, and facilitating graduate education.

Table 1. Selected private research foundations in Namibia.

[RELATED: How China Took Over University Climate Science to Weaken America]

ISFs can also offer an escape from the stifling conformity that comes with the rise of the all-administrative university and attendant fall of the faculty, as Bernard Ginsberg has dubbed it. Universities today are trapped into a silo model of education, in which professors may only offer instruction to the limited set of matriculated (i.e., tuition-paying) students at the university that employs them. This is the most expensive and least efficient means imaginable of delivering instruction to students. It can only be made to work by universities having a monopoly on higher education. This model is obsolete and unsustainable in the networked world that has emerged over the past several years, however. Yet, universities are constitutionally unprepared and unwilling to rise to the challenge, as demonstrated by the disastrous forced entry of universities into online education five years ago in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Higher education and legacy media thus both occupy a similar landscape, both held up by a monopoly hold on the production and distribution of content to a captive public. As the means of distribution have loosened, and production costs of high-quality content have fallen, the monopoly for both legacy media and higher education has been undermined. In its place, a new landscape that is more innovative, creative, and nimble, is emerging as an alternative to the legacy media.

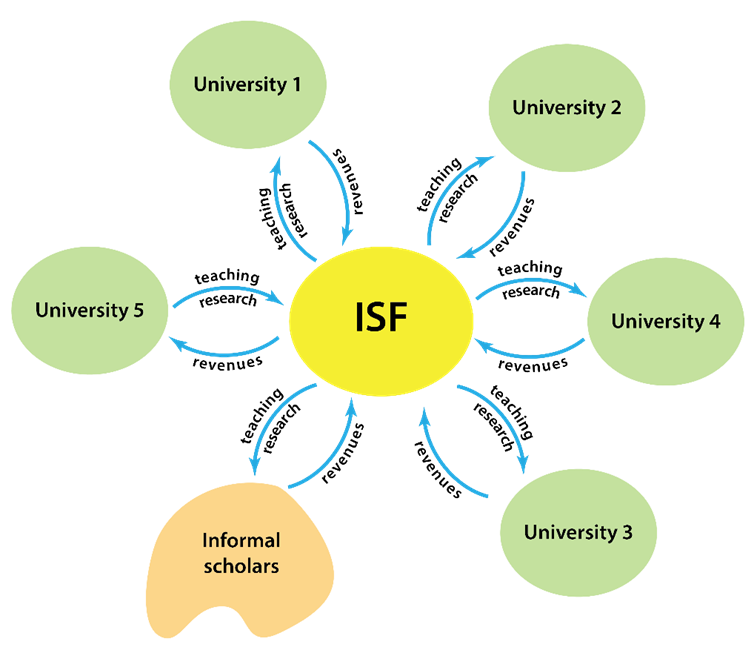

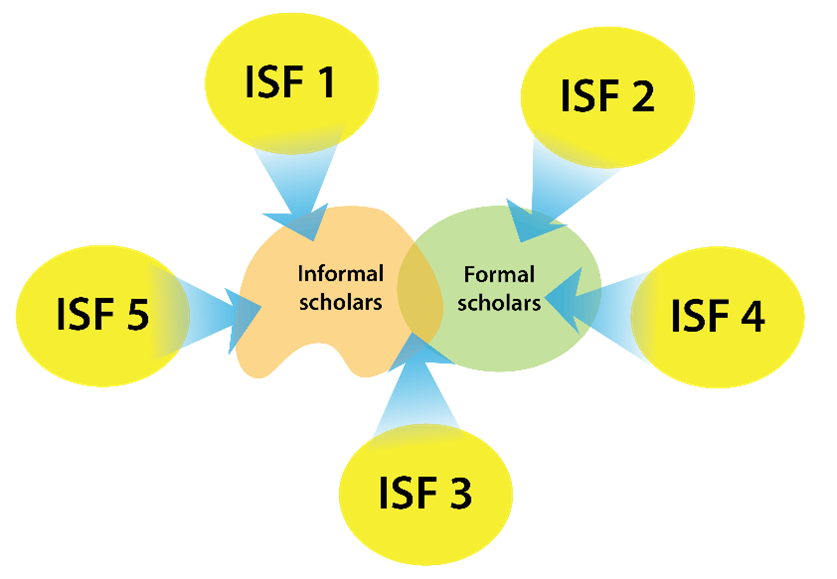

Just as the “three-letter networks” are looking ever more like lumbering dinosaurs, so too are the universities. ISFs could offer the means for scientists to unlock the creativity and versatility that is their most prominent characteristic, but is suppressed in the protectionist model of the modern university. For example, an ISF is not bound to a contract with one university that might share its physical space. In a networked world, our hypothetical Salviati Life Sciences could offer its services to many other universities. It could even reach out more effectively to learners that universities now shun as free riders (Figure 2). Nor need there be just one ISF for, say, biology; there could be many, forming a diffuse network of nodes for scholars seeking to learn about biology (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The ISF as a node in an increasingly networked education and scientific world. Top: An ISF can serve multiple universities and groups of informal scholars. Bottom: Multiple ISFs can compete for a broad marketplace of formal (degree-seeking) and informal (non degree seeking) scholars.

Such diffuse networks of ISFs would introduce a competitive incentive to scientists to innovate and explore alternate ways of teaching and doing science, which universities have mostly proven unable to do. Universities could still offer degrees and set standards for granting the degree, but they would no longer exercise monopolistic control over content and delivery. While there certainly would be significant challenges, the opportunities for innovation and creativity in networks of ISFs are vast, and they would put scientists themselves back in control of their professions and their own destinies.

Something worth a try, I’d say.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Illustration by Jared Gould made using Grok — Scientist as serfs modeled off of Queen Mary Master on Wikipedia

Wow — this reminds me of the Germans who voted for the Nazis in 1933 because they didn’t like the Communists. Things would be a LOT worse than they are now….

I’m going to leave out the legal profession beyond saying that,for most lawyers, it is not the nirvana that you describe. I’ll just deal with your MD analogy because there is what it was like to go to the doctor’s office in the 1970s or 1980s and what it is like now.

Today, you are lucky if the MD makes eye contact with you twice as he furiously types into his computer. My mother had three different electrocardiograms that discussed her pacemaker and its leads — except that she doesn’t HAVE a pacemaker. MDs don’t practice medicine anymore, instead they work for the insurance company and their own managed care company.

In the hospital today, you have to have an IV, even if not medically needed, because the insurance company won’t let you be in the hospital if you don’t. There used to be MDs practicing in their 70s & 80s because they loved it. Now they’re taking early retirement as soon as they can afford it, often in their late 50s…

“Let us call these Independent Science Faculties (ISF)… In an ISF, scientists would no longer be subordinate employees of universities.”

No, instead they’d be subordinate employees of the ISF. See above about Nazis being worse than Communists in the 1933 Wiemar Republic election.

Your analogy fails, I’m afraid, not just because you went full Godwin, but because medicine has been as captured by federal bureaucracy as thoroughly as science has, and with the same destructive consequence. For academic science, universities are now playing roughly the same roles as health insurance conglomerates are for medicine: middlemen that depend upon capturing vast streams of taxpayer money.

I too have memories from the 60s when our family physician made house calls. Try that now. That’s been destroyed by the commoditization of medicine. Commoditizing education and science have had the same consequence.

I have spoken to lawyers about their experiences in law firms. The story I’ve heard has been the same: they have more freedom as partners in a law firm than they ever would have serving as government or corporate attorneys.They have more freedom because their firms are essentially small businesses who have more effective control over their professions.

I hear similar stories from groups of physicians who form small practices, precisely to escape from the mega-conglomerate health management firms that dominate health “care”, and again, are governed mostly by the capture of insurance money (really federal and state money if you trace it out). That is the reason for the impersonal encounters you describe: the physician no longer has the patient as client, he works for someone else. The patient is just the turnkey to the money.

Small practices, on the other hand, are where you are most likely to find physicians who still treat their patients as clients, and where innovation comes from, like concierge medicine, for example.

Scientists forming ISFs would be like those small private practices, and would enable scientists, particularly scholar scientists, to be back in control of their professions. I can say from personal experience in my own academic career that individual creativity and innovation are not welcome in today’s universities. Every time I tried to innovate, I faced an endless gauntlet of people telling me “you can’t do that.” Most of my career was developing workarounds to those obstacles.

First, how many lawyers make partner? I’d say it is about the same as professors who make dean — and hence you are taking a minority viewpoint in either case.

But the bottom question you have to answer is where does the revenue stream come from and why. Concerge medicine is funded by persons with the means and desire to have personalized medicine, you will not find it in low-income neighborhoods. In fact, it will not be long before those practicing it run into market saturation as it is a relatively small market.

So too with concerge science — it’s called “private tutoring” and already exists.

Since 1965, science has been funded by government money provided for undergraduate tuition. How do you propose changing that model?

And much as you state with healhcare, the exact same thing will happen with education (not “science” because it is “education” that is being funded.

Existence determines consciousness. The Marxists didn’t have a solution but they were good at analyzing problems with society. As discourse analysis teaches us, the topics not addressed are the ones that are important. Here, the topic not addressed is the slave labor (graduate students and post-docs) used to support the hierarchical system that seems so important to the author to maintain. Here’s a suggestion–emulating European universities, use the staff scientist organization rather than lowly paid, soon to be discarded, graduate students and post-docs. It would still be hierarchical but it would create a humane atmosphere for the underlings, in addition to them being able to support themselves and their families by not stealing food from departmental seminars.

Graduate students are certainly exploited, but this is kept in place by most graduate student support being tied to grants. Another form of serfdom, really. One of our suggestions (not written here, but will be in the larger Rescuing Science report, is to model all graduate student support after the Graduate Research Fellowships model, in which the support goes with the student, as opposed to chaining the student to a grant.

I guess I’m not troubled by hierarchy. It’s the natural outcome of having pathways of advancement.

As to modeling things after European universities, that might be the outcome of scientists leaving the universities and setting up ISFs. A range of models might emerge in fact, which could compete, and a natural one emerges. Or many models might exist.

Certainly, the experiment to transplant the Oxbridge-style campus to the US failed.

It’s not just the Oxford-style campus but the 19th Century vocational origins of nearly all of our public IHEs — nearly all started either as normal schools (teacher’s colleges) or land grant universities, the latter being to teach “scientific agriculture and mechanical arts” (A&M) to farmers to make them more productive.

We did copy the German model late in the 19th Century and then created our own National Defense model during the 50 years war (1941-1991) but now it’s a question of what the country needs and hence what it should support.

From an appropriations perspective, supporting science for the sake of supporting science is, quite frankly, asinine. And the worst part of it is that the social sciences will be there with a “me, too” demand, and then the humanities as well, and we wind up spending money (that we don’t have) researching the sex lives of gay frogs in the Amazon or the exact dimensions of Shakespeare’s stage while the Chinese build a bigger navy than ours.

And the problem with the treatment of graduate students today is that the reward is no longer there — the odds of winning are approaching that of the local casino. Perhaps we should tax the 6-figure salaries of professors (and retired professors) to supplement the income of adjuncts and others holding PhDs…

It’s not just the Oxford-style campus but the 19th Century vocational origins of nearly all of our public IHEs — nearly all started either as normal schools (teacher’s colleges) or land grant universities, the latter being to teach “scientific agriculture and mechanical arts” (A&M) to farmers to make them more productive.

We did copy the German model late in the 19th Century and then created our own National Defense model during the 50 years war (1941-1991) but now it’s a question of what the country needs and hence what it should support.

From an appropriations perspective, supporting science for the sake of supporting science is, quite frankly, asinine. And the worst part of it is that the social sciences will be there with a “me, too” demand, and then the humanities as well, and we wind up spending money (that we don’t have) researching the sex lives of gay frogs in the Amazon or the exact dimensions of Shakespeare’s stage while the Chinese build a bigger navy than ours.

And the problem with the treatment of graduate students today is that the reward is no longer there — the odds of winning are approaching that of the local casino. Perhaps we should tax the 6-figure salaries of professors (and retired professors) to supplement the income of adjuncts and others holding PhDs…