Editor’s Note: The following is an article originally published on Free Black Thought on May 26, 2025. With edits to match Minding the Campus’s style guidelines, it is crossposted here with permission.

What follows is an excerpt on “race” and “race pride” from a speech that Frederick Douglass delivered before a large crowd on September 3, 1894, less than 6 months before his death at age 77. The speech is titled, “The Blessings of Liberty and Education: An Address Delivered in Manassas, Virginia.” The occasion was the dedication of the Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth. We produced this edition of the text directly from the typescript from which Douglass read and which he corrected in pencil.

Clipping of The New Manassas newspaper containing the text of the speech by Frederick Douglass that we have excerpted here. From the Frederick Douglass Papers in the Library of Congress.

I have a word now upon another subject, and what I have to say may be more useful than palatable. That subject is the talk now so generally prevailing about races and race lines. I have no hesitation in telling you that I think the colored people and their friends make a great mistake in saying so much of race and color. I know no such basis for the claims of justice. I know no such motive for efforts at self-improvement. In this race-way they put the emphasis in the wrong place. I do now and always have attached more importance to manhood than to mere kinship or identity with any variety of the human family.

From the typescript that Frederick Douglass read from when he delivered the speech excerpted here. From the Frederick Douglass Papers in the Library of Congress.

RACE, in the popular sense, is narrow; humanity is broad. The one is special, the other is universal. The one is transient, the other permanent. In the essential dignity of man as man, I find all necessary incentives and aspirations to a useful and noble life. Man is broad enough and high enough as a platform for you and me and all of us. The colored people of the country should advance to the high position of the Constitution of the country. The Constitution makes no distinction on account of race and color, and they should make none.

We hear, since emancipation, much said by our modern colored leaders in commendation of race pride, race love, race effort, race superiority, race men, and the like. One man is praised for being a race man and another is condemned for not being a race man. In all this talk of race, the motive may be good, but the method is bad. It is an effort to cast out Satan by Beelzebub.

The evils which are now crushing the Negro to earth have their root and sap, their force and mainspring, in this narrow spirit of race and color, and the Negro has no more right to excuse and foster it than have men of any other race. I recognize and adopt no narrow basis for my thoughts, feelings, or modes of action. I would place myself, and I would place you, my young friends, upon grounds vastly higher and broader than any founded upon race or color.

Neither law, learning, nor religion is addressed to any man’s color or race. Science, education, the Word of God, and all the virtues known among men, are recommended to us, not as races, but as men. We are not recommended to love or hate any particular variety of the human family more than any other. Not as Ethiopians; not as Caucasians; not as Mongolians; not as Afro-Americans, or Anglo-Americans, are we addressed, but as men.

God and nature speak to our manhood, and to our manhood alone. Here all ideas of duty and moral obligation are predicated. We are accountable only as men. In the language of Scripture, we are called upon to “quit ourselves like men.”

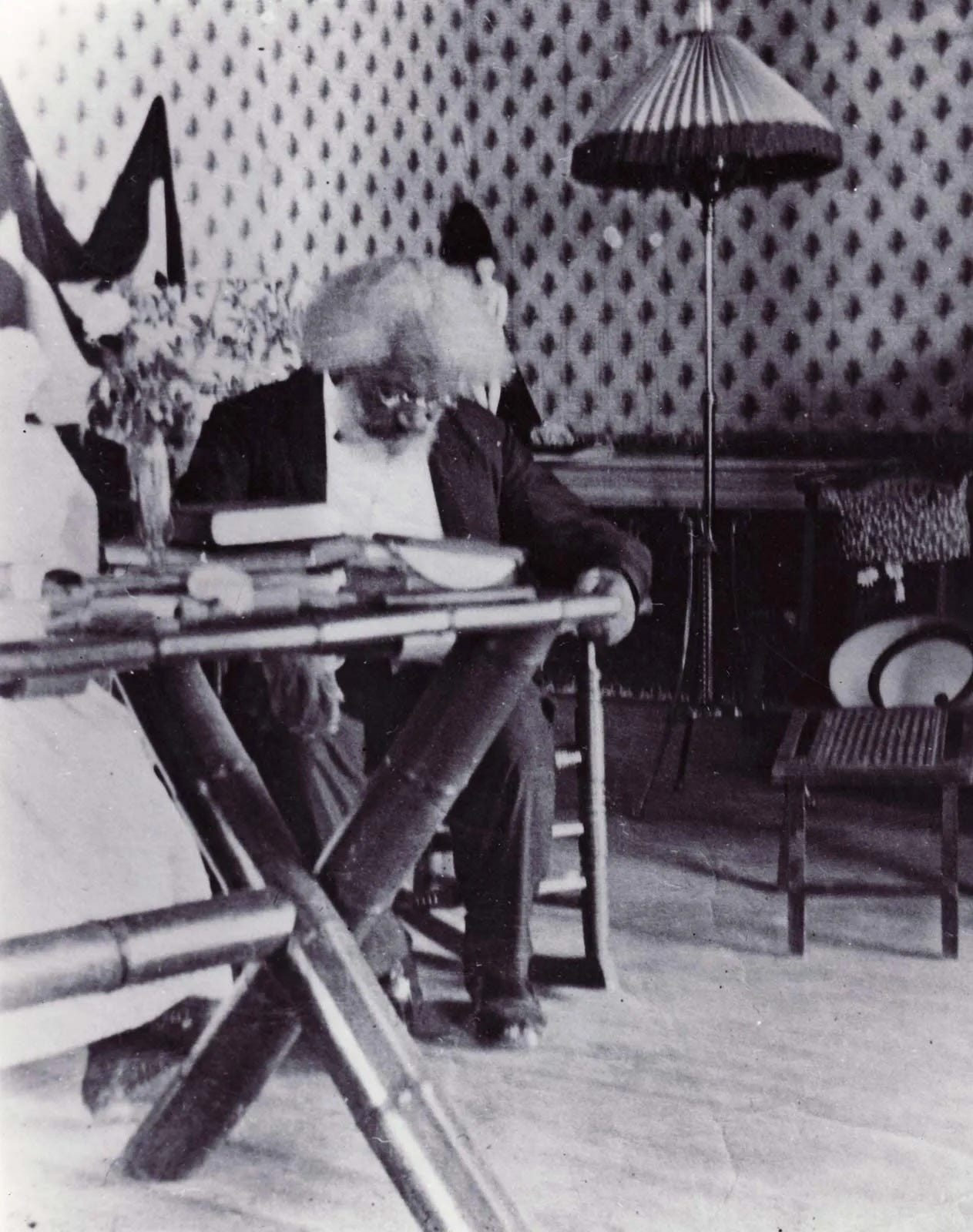

Frederick Douglass at his desk, c.1890.

To those who are everlastingly prating about race men, I have to say: Gentlemen, you reflect upon your best friends. It was not the race or the color of the Negro that won for him the battle of liberty. That great battle was won, not because the victim of slavery was a Negro, mulatto, or an Afro-American, but because the victim of slavery was a man and a brother to all other men, a child of God, and could claim with all mankind a common Father, and therefore should be recognized as an accountable being, a subject of government, and entitled to justice, liberty and equality before the law, and every where else. Man saw that he had a right to liberty, to education, and to an equal chance with all other men in the common race of life and in the pursuit of happiness.

You know that, while slavery lasted, we could seldom get ourselves recognized in any form of law or language, as men. Our old masters were remarkably shy of recognizing our manhood, even in words written or spoken. They called a man, with a head as white as mine, a boy. The old advertisements were carefully worded: “Run away, my boy Tom, Jim or Harry,” never, “my man.”

Hence, at the risk of being deficient in the quality of love and loyalty to race and color, I confess that in my advocacy of the colored man’s cause, whether in the name of education or freedom, I have had more to say of manhood and of what is comprehended in manhood and in womanhood, than of the mere accident of race and color; and if this is disloyalty to race and color, I am guilty. I insist upon it that the lesson which colored people, not less than white people, ought now to learn, is that there is no moral or intellectual quality in the color of a man’s cuticle; that color, in itself, is neither good nor bad; that to be black or white is neither a proper source of pride or of shame.

I go further, and declare that no man’s devotion to the cause of justice, liberty, and humanity, is to be weighed, measured and determined by his color or race. We should never forget that the ablest and most eloquent voices ever raised in behalf of the black man’s cause, were the voices of white men. Not for the race; not for color, but for man and manhood alone, they labored, fought and died.

Frederick Douglass with Gerrit Smith and other abolitionists at an abolitionist gathering in Cazenovia, New York, August 1850.

Neither Phillips, nor Sumner, nor Garrison; not John Brown, nor Gerrit Smith were black men. They were white men, and yet no black men were ever truer to the black man’s cause than were these and other men like them. They saw in the slave, manhood, brotherhood, womanhood outraged, neglected and degraded, and their own noble manhood, not their racehood, revolted at the offence. They placed the emphasis where it belonged; not on “the mint, anise and cummin” of race and color, but upon manhood and “the weightier matters of the law.”

Thus compassed about by so great a cloud of witnesses, I can easily afford to be reproached and denounced for standing, in defense of this principle, against all comers. My position is, that it is better to regard ourselves as a part of the whole than as the whole of a part. It is better to be a member of the great human family, than a member of any particular variety of the human family. In regard to men as in regard to things, the whole is more than a part. Away then with the nonsense that a man must be black to be true to the rights of black men. I put my foot upon the effort to draw lines between the white and the black, or between blacks and so-called Afro-Americans, or to draw race lines anywhere in the domain of liberty. Whoever is for equal rights, for equal education, for equal opportunities for all men, of whatever race or color,— I hail him as a “countryman, clansman, kinsman and brother beloved.”

***

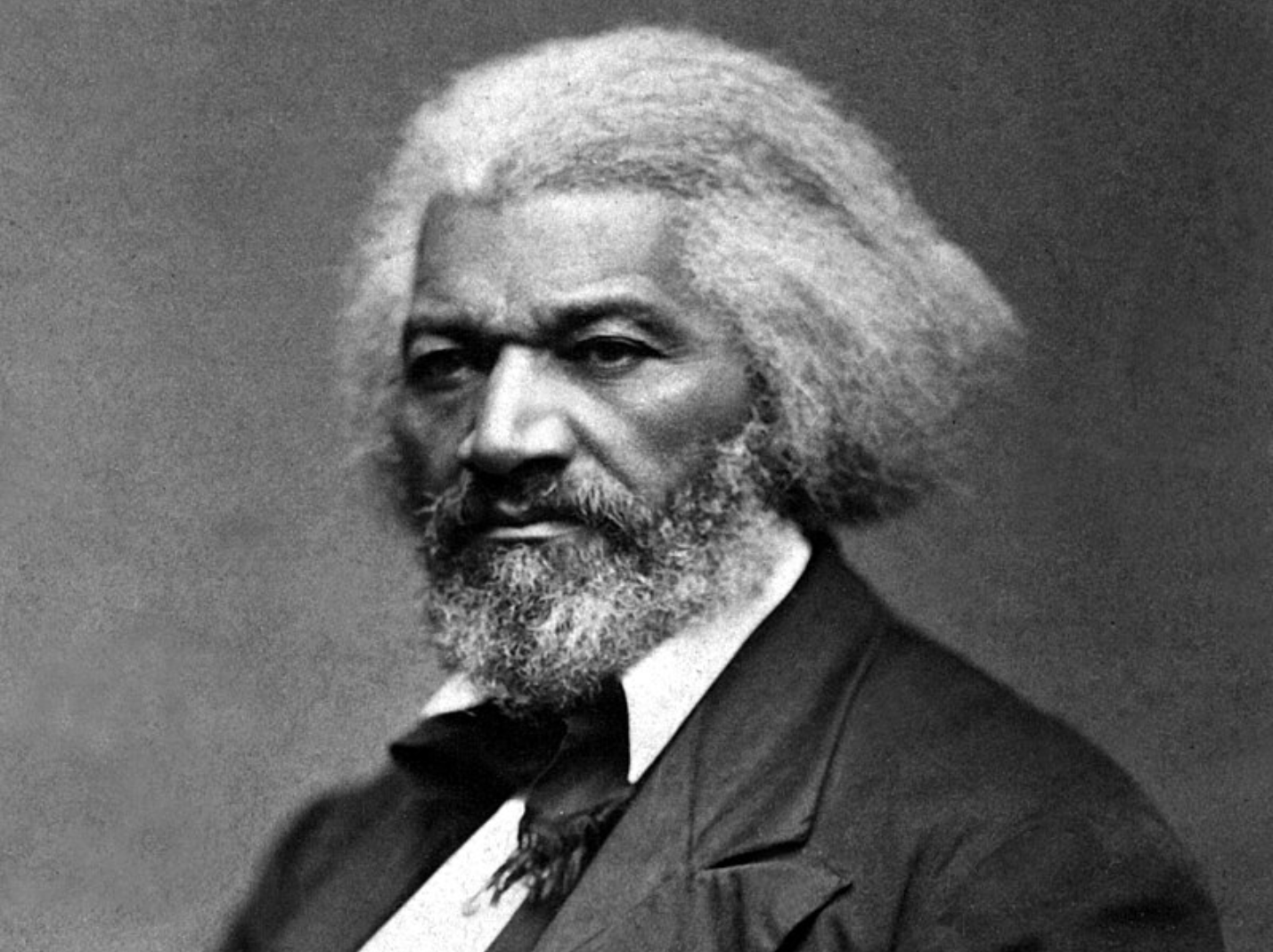

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland in February of 1818 and died on February 20, 1895, having lived the final 57 years of his life as a free man. Douglass liberated himself from slavery in 1838 with the help of Anna Murray, soon to be his wife, who was a free black woman, an Abolitionist, and a member of the Underground Railroad living in Baltimore. She got him the money, disguise, and identification papers that he needed to carry out the plan of boarding a northbound train dressed as a sailor and thus make his way to New York City.

After escaping slavery, Douglass joined with the white Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, but eventually split with Garrison over the proper interpretation of the Constitution. Garrison thought it was a pro-slavery document that needed to be discarded, whereas Douglass came to believe that it was a “glorious liberty document” that nowhere contained “the right to hold property in man” and that properly interpreted “would put an end to slavery in America.”

Douglass wrote and lectured tirelessly to defeat slavery and then, after the Civil War, to better the lot of black Americans, to secure women the right to vote, to promote immigration and a multi-racial conception of American identity, and to advance equality and civil rights for all.

In addition to his many speeches and articles, Douglass wrote three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845); My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881/1892). The Library of Congress’s Frederick Douglass papers, 1841-1967 are available here.

Follow Free Black Thought on X.