Note: July 2025 will mark the centenary of the famous Tennessee “Scopes Monkey Trial.” This article is part of a series leading up to the centennial events in Dayton, Tennessee, the site of the trial.

In the summer of 1925, the town luminaries of Dayton, Tennessee, summoned John T. Scopes from his tennis game to meet them at Robinson’s drugstore. They wanted to discuss a plan. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had been plaintiff-shopping for a test case for overturning Tennessee’s House Bill No. 186, also known as the Butler Act:

… prohibiting the teaching of the Evolution Theory in all the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of Tennessee, which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, and to provide penalties for the violations thereof.

The ACLU had not found any takers in the more cosmopolitan city of Chattanooga, so Dayton’s town leaders thought to themselves, “Why not us? Maybe we could put our town on the map?” So, they asked Scopes, a substitute teacher and football coach who had been filling in for the regular biology teacher, if he’d volunteer to be the plaintiff. Having nothing better to do that summer, Scopes agreed, kicking off the biggest three-ring circus ever to come to Dayton: the “Scopes Monkey Trial.”

Once the ACLU had its plaintiff in hand, William Jennings Bryan—the “Prairie Populist,” a former Secretary of State in the Wilson administration, and a three-time presidential candidate—volunteered to serve on the prosecution. Once Bryan put his hand in, Clarence Darrow, the Chicago 1920s version of Johnny Cochran, felt he had to do the same. HL Mencken, sensing a golden opportunity to lampoon the yokels of the “Coca-Cola belt,” threw in his hat, making the pilgrimage to Dayton from his paper, the Baltimore Evening Sun, to report on the strange-goings on with Homo sapiens’ troublesome southern congener, Homo neandethalensis. Ringmasters in place, the circus came to town in July 1925. For a week, Dayton was the center of the world’s attention.

Thirty years later, Jerome Lawrence and Robert E Lee dramatized the Scopes trial in a stage play, Inherit the Wind. Five years after that, Stanley Kramer adapted the play for the movie of the same name.

To call Inherit the Wind a dramatization of the Scopes trial is misleading: verisimilitude would be a more apt descriptor. An accurate description of the Scopes trial would not have played well on Broadway. There was intrigue and drama, to be sure, but little of it in the trial itself. It was not really Scopes who would be on trial, but the Butler Act. The prosecution obviously wanted a conviction so that the Butler Act would be upheld. The defense was also eager for a conviction, but only as the pretext for an appeal. Mencken wanted good copy for his newspaper. The guilt or innocence of Scopes himself was essentially irrelevant, as he described himself more as a spectator than a defendant.

In the end, Scopes was convicted and fined $100, so the prosecution got what it wanted. The defense was deprived of its test case, though. The trial judge set Scopes’ fine in a way that ensured the conviction would quickly be overturned. The Butler Act was left unperturbed and remained on the books for another forty-two years. Scopes himself went back to the untroubled normal life he had enjoyed before the circus came to town. Dayton went back to its peaceful and placid pre-trial existence. In short, the Scopes trial changed nothing. Not exactly the makings for high drama. You can see the playwright’s challenge.

[RELATED: WATCH: Why Scientists Aren’t Really Leaving—and Why Chimps Aren’t 99% Human]

Fortunately for Lawrence and Lee, the ringmasters were determined to gin up drama. Even though the defense wanted an expeditious conviction, they still had to maintain the façade of a defense. The defense loaded up its case with an impressive array of expert witnesses who could testify to the scientific basis of evolution. The trial judge disallowed their testimony as immaterial to the case at hand, namely, whether or not Scopes violated the Butler Act. In court, the defense fell back on histrionic posturing and baiting the judge. Also, both Darrow and Bryan were playing to larger audiences outside the courtroom. Their extrajudicial antics gave Lawrence and Lee the dramatic fodder they needed for their play: to portray the most dramatic parts of the three-ring circus as part of the trial, turning Inherit the Wind into a courtroom drama about evolution. Shades of Galileo! Hence the verisimilitude.

Lawrence and Lee patched all these elements into the fictionalized hodgepodge that became Inherit the Wind. In the play, Scopes was arrested while teaching evolution in his classroom: that never happened. Scopes was locked up in the town jail: that never happened. Scopes had to have a love interest, introduced in the first act as the daughter of a fire-and-brimstone fundamentalist preacher who disowned her: she never existed. Darrow’s dramatic confrontation with Bryan took place in the courtroom: Nope, it actually took place on the lawn outside the courthouse for the entertainment of the crowd. The jury was not allowed to consider it. In the play, the Bryan character was so unnerved and humiliated by Darrow’s questioning that he fell over dead at the trial’s end, smote by the god of science. Well … Bryan did die five days after the trial, not from a “busted belly” as Darrow supposedly said, but from a stroke. Scopes himself described Bryan as upbeat after his supposed humiliation at Darrow’s hand, and looking forward to the appeal. Much of the dramatic arc and tone of the play did not reflect the actual trial, which was dominated by back-and-forth motions and maneuverings from the prosecution and defense, mainly with the jury absent. The play’s dramatic arc borrowed more from Mencken and his vitriolic pen, who held nothing back in his visceral disdain for the dangerous species of southern yokels and their snake-handling, glossolalia, and fundamentalist superstition.

After its unpromising debut in Dallas, Inherit the Wind proved to be a winner, transitioning from Dallas into a long-running Broadway production, garnering awards, and inspiring numerous stage revivals in subsequent decades. Lawrence and Lee had produced a hit.

Stanley Kramer masterfully adapted Lawrence and Lee’s script for the silver screen, aligning with his penchant for “controversial” films that champion progressive causes. Among his credits were On the Beach, Judgment at Nuremberg, The Caine Mutiny, and others. Shot in Kramer’s signature black and white, Inherit the Wind is a great film, with a great cast. Spencer Tracy played the Darrow character, Fredric March channeled Bryan, and the suave Gene Kelly was miscast as the misanthropic Mencken. Dick York, who played the Scopes character, is better known as Darrin Stephens, the mortal husband of Samantha the good witch in the ‘60s sitcom Bewitched (1964-1969).

Kramer sets the tone right from the beginning. Five men, one flashing a badge, march across town to the high school, accompanied by a dissonant rendering of Give Me That Old Time Religion. At the school, they stop York/Scopes at his first mention of Charles Darwin’s name, and haul him away to the jail. As the trial approaches, March/Bryan is escorted into Dayton at the front of a festive entourage of dignitaries, marching bands, and hymn-singing women. The next day, Tracy/Darrow arrives unheralded on a bus with other commoners, the modest warrior girding for battle. At their boardinghouse, March/Bryan is a garrulous glutton, surrounded by fawning admirers, while Tracy/Darrow sits at another table, alone at his modest repast. In the courtroom, Tracy/Darrow is the lonely stalwart for truth, while March/Bryan plays to the mob. Kelly/Mencken flits about like a cynical Puck. There is even a Madame LaFarge character sitting in the courtroom gallery, her knitting punctuated by cackling outbursts as she watches Scope being marched to the scaffold.

[RELATED: The Evolution of Intelligent Design Theory]

Both March and Tracy delivered signature performances. In the courtroom scenes, both marched about the set eating the scenery, with much loud shouting, grandstanding, speechifying, arm-waving and glaring at one another. In my view, March put in the better acting performance, although the makeup artist did him no favors. Tracy, for his part, played, well, Spencer Tracy: gruff, wrinkled, unkempt, a persona he could have switched in from any of his other movie roles. It was unfair of me, but I couldn’t take York seriously as Scopes. Every time he appeared on the screen, I reflexively thought of Bewitched and Samantha.

You can see Kramer’s Inherit the Wind on Amazon Prime Video. It’s a great film, worth a couple of hours of your time to watch. As for Inherit the Wind being about the Scopes trial, let us just say that … liberties were taken. Such is the license we grant the artist.

Lawrence and Lee wrote Inherit the Wind as a sort of The Crucible for the Coca-Cola belt—swapping out witches for creationists. Just as the people of Salem were led by superstition to sniff out witches, the people of Tennessee (the play suggests) were led by the same backward forces to ban the teaching of evolution. The subtext practically shouts: Can’t you see it’s the same mistake all over again? But instead of persuasion, I hear a screech—fingernails on the chalkboard of my mind. The play isn’t content to dramatize a debate; it wants to instruct me. Evolution is truth and light. Creationism is ignorance and darkness. And of course, darkness must be stamped out—urgently, and by force if necessary. That’s the sermon echoing behind the curtain.

Thus, it was right and proper for the ACLU to barge in to overrule the Tennessee legislature, just as it was right and proper to oppose Tail Gunner Joe McCarthy and his comrades in the House Un-American Activities Committee. Never mind that communist infiltration of the government and film industry was a real problem in the 1950s, or that the Butler Act was the democratically determined will of the people of Tennessee. I know the parallels are piling up like pickup sticks here, but can’t you see they’re the same?! Well, no, not really. Inherit the Wind might have been great cinema, but it has to be viewed for what it was: Cold War agitprop.

The deceptive legacy of Inherit the Wind has endured. Since 1925, there have been at least ten instances of legal challenges over the place of evolutionism in the public schools. In every instance, it was states or school boards daring to set a curriculum for their own students. In every instance, their presumption was met by a bullying insistence that no, they won’t. In every instance, the opposition has draped itself with the mantle of Inherit the Wind. Evolutionism is truth and light, and anti-evolutionism is bigoted superstition, which cannot stand. Parents, schools, and school boards may not be allowed to set their own curricular standards for their children if they depart from the Darwinian party line. Otherwise, we are on an imagined slippery path to a theocratic hellhole.

Just as the Scopes trial itself resolved nothing, the annoying superciliousness of Inherit the Wind abides.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

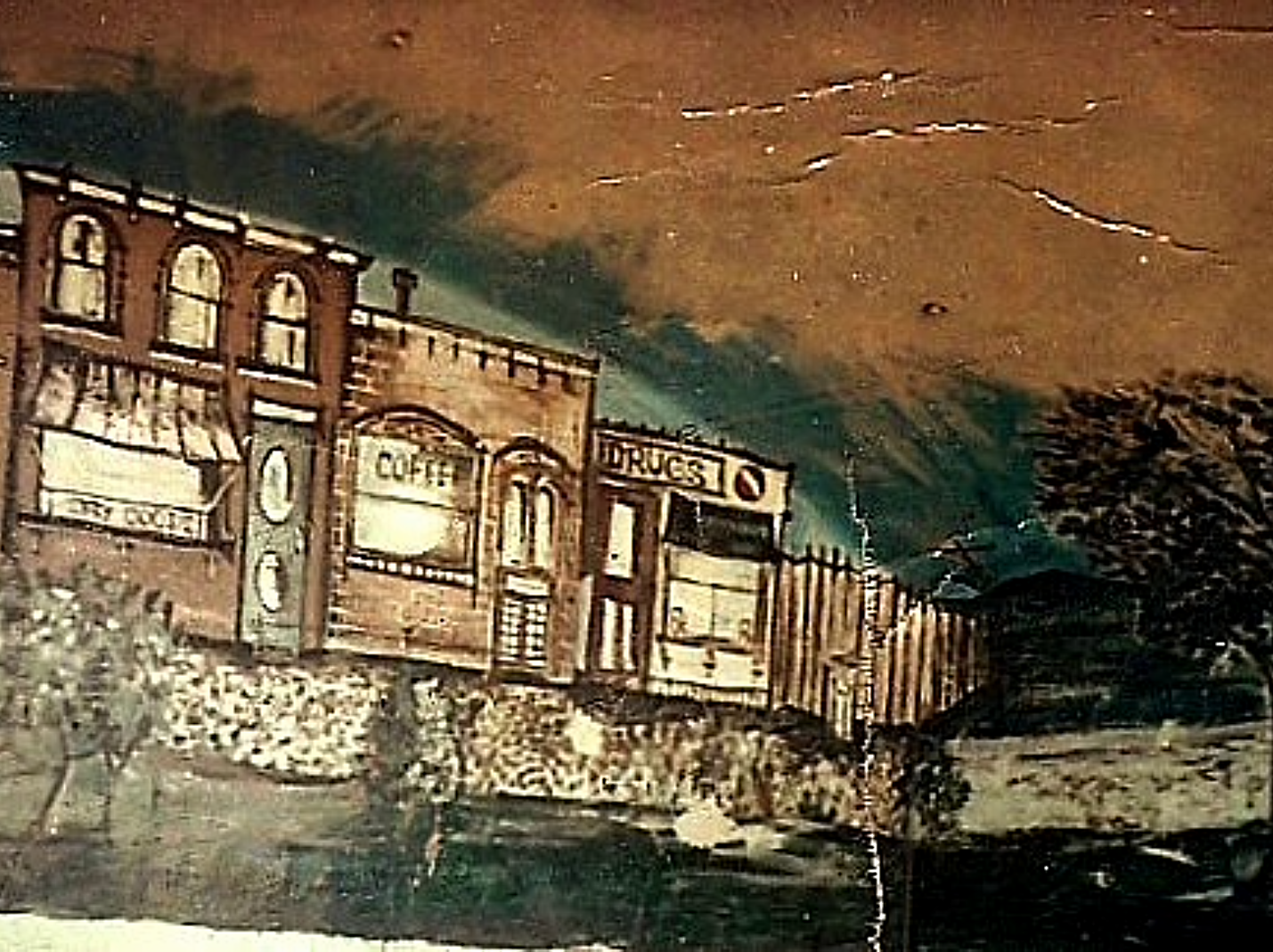

Image: “‘INHERIT THE WIND’ STAGE SET DESIGN 1967” by Robert Huffstutter on Flickr