Author’s Note: July 2025 will mark the centenary of the famous Tennessee “Scopes Monkey Trial.” This is the second article in a series leading up to the centennial events in Dayton, Tennessee, the site of the trial. Read the first in the series here.

A century ago, the world’s greatest three-ring circus was about to come to Dayton, Tennessee. The Tennessee legislature had passed the Butler Act, forbidding the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Governor Austin Peay signed the Butler Act into law on March 21, 1925. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) determined to challenge it on First Amendment grounds. The Dayton town luminaries offered up a willing plaintiff in John T Scopes, a substitute science teacher and coach at Dayton’s high school, who volunteered to claim he had defied the Butler Act. In return, the ACLU would expeditiously escort Scopes to the conviction they needed for their appeal.

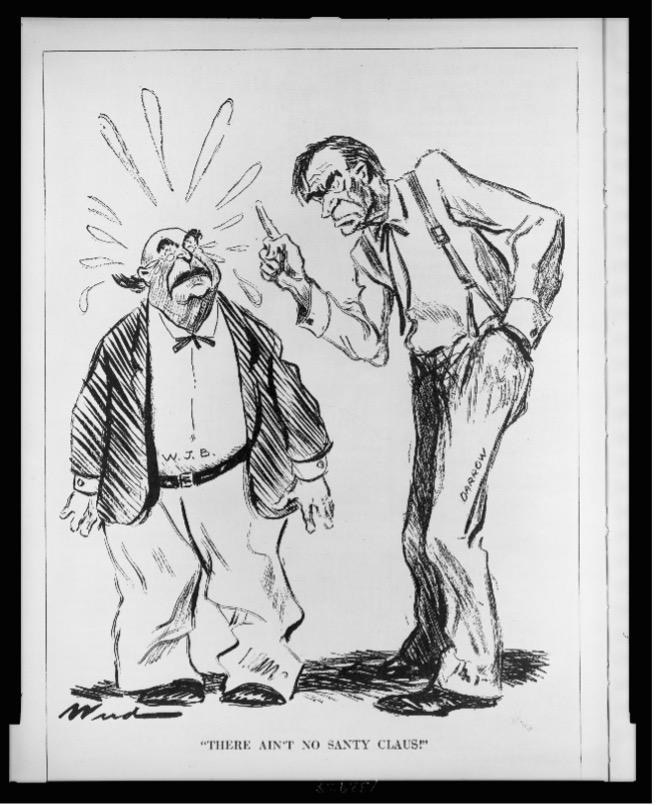

Figure 1. There ain’t no Santy Claus! Clarence Darrow (left) confronting William Jennings Bryan at the Scopes trial. Source: Library of Congress

The defense team that would descend on Dayton consisted of John Neal, a University of Tennessee law professor; Dudley Field Malone, who had served in Woodrow Wilson’s State Department; Arthur Garfield Hays, who was representing the ACLU; and Clarence Darrow, who joined the defense team when he learned that William Jennings Bryan would be leading the prosecution.

Even though the defense aimed for a conviction, they still had to maintain a façade of defending Scopes, so they built their case around painting John Scopes as a latter-day Galileo, and the State of Tennessee as the Roman Inquisition. In support, the defense brought in a distinguished group of scientists who could provide expert testimony on the science of evolution. Two of them were also prominent figures in their respective churches.

[RELATED: WATCH: Why Scientists Aren’t Really Leaving—and Why Chimps Aren’t 99% Human]

The prosecution did not want these experts to testify, arguing that whatever they had to say about evolution would be immaterial to the question at hand, namely, whether John Scopes had violated the Butler Act. To help him make up his mind, Judge John T. Raulston allowed the defense to call one of its expert witnesses, Professor Maynard Metcalf, a professor of zoology at Johns Hopkins. In the end, Judge Raulston agreed with the prosecution. Prof Metcalf’s testimony would be stricken from the record, and the rest of the defense’s experts would not be allowed to testify. As a concession to the defense, Judge Raulston invited Metcalf and the other expert witnesses to submit written statements to be included in the trial record.

For excluding the experts’ testimony, Judge Raulston has been widely condemned for railroading Scopes to a conviction. To the contrary, the judge probably did the defense a favor, since a conviction was precisely what they wanted. Had the experts been allowed to testify, sufficient reasonable doubt likely would have been sown in the jury’s mind to acquit Scopes, scuttling the defense’s strategy.

The defense intended their experts to paint evolution as a crystal truth, beyond the power of legislatures to regulate. Judging from their written statements, neither clarity nor consistency was forthcoming. One expert was a soil scientist, whose argument seemed to be that soils transform from one form to another over time, and that this is a form of evolution. As most of the jurors were farmers, this would hardly have been news. Another pointed to the immense age of rocks, something that not even the prosecution contested. Two others asserted that teaching geology, never mind teaching biology, would be impossible if the Butler Act was allowed to stand. Others’ testimony paralleled Prof Metcalf’s, which amounted to a long—and I have to say, pedantic—discourse on evolution’s broad scope, as if he were delivering an introductory lecture to a classroom of undergraduates. Overall, the defense seems to have overestimated the likelihood that their experts would deliver a consensus.

The vague language of the Butler Act itself also would have been a strong hand for the defense, had they wanted to pursue an acquittal. The actionable language of the Butler Act proscribed any teaching of human origins that contradicted the account in Genesis, and that man was descended from a “lower order of animals.” The experts fared no better on these questions than they did defining evolution as truth. Two experts offered evidence from hominid fossils to demonstrate the descent of man from “lower orders.” Unfortunately, both included the fraudulent Piltdown man fossils in support. And just what was the “lower order” spelled out in the act? Was it limited to primates? Or more broadly, to mammals? Or still more broadly to vertebrates? Or all the way back to the bacteria? Technically, every interpretation of “lower order” could be the correct one, leaving the jury to parse out the Butler Act’s impossible language. The jury likely would have concluded that, like felonious mopery, the Butler Act was so vaguely worded that it anything could be considered a violation, and that no defendant could be held accountable for violating it.

[RELATED: The Evolution of Intelligent Design Theory]

The defense also sought to have its experts establish that evolution could not undermine the “Divine Creation of man” as specified in the Bible and the Butler Act. The experts, who included prominent churchgoers as well as scientists, were no better in helping with evolution per se. Prof Metcalf, for example, worked himself into a flat contradiction. He purported to reconcile evolution and religion by espousing a doctrine of “theistic evolution,” which could be directed by a divine hand. Disagreement of science and religion would thereby be made logically impossible, and therefore making it logically impossible for evolution to undermine the divine creation of man. In fact, theistic evolution invalidates the Darwinian idea. Had his testimony been allowed to stand, Prof Metcalf would have been the prosecution’s best witness.

If that were not enough, Prof Metcalf wove himself into another logical contradiction. The Butler Act’s intent was to protect religious belief from being undermined by science, with evolution serving as science’s stalking horse. At the same time Metcalf was arguing that it was logically impossible for science to undermine religion, he argued that, for both to thrive, science and religion had to be strictly segregated. Either teaching evolution poses no threat to religion and vice-versa, or each poses a mortal threat to the other. In the end, Prof Metcalf himself came down as a strict segregationist. To quote from his own statement, allowing religious belief to intrude upon science in the schools would be tantamount to “criminal malpractice.”

Without its experts’ testimony, the defense had to fall back on deflection and histrionics, the trial lawyer’s well-established tactic for a guilty client, except in this case to get a conviction. Clarence Darrow was the master of this tactic, which he wielded throughout the Scopes trial. He demanded that the judge remove a banner over the courthouse door with the exhortation to “Read Your Bible.” If the judge wouldn’t accede, Darrow demanded that another banner be put up saying, “Read Your Darwin.” The argument over excluding the expert witness’s testimony became so acrimonious that it earned Darrow a contempt citation. He engaged witnesses with picky points over Bible translations and different Bible versions. He sarcastically asked the students who had been in Scopes’s classroom whether they had been harmed by knowing about evolution. He trotted out the usual arguments of the superficial skeptic. Where did Cain’s wife come from? Did Joshua really stop the Earth’s rotation? And he engineered the trial’s dramatic, albeit legally inconsequential, apex: calling William Jennings Bryan to the stand, ostensibly as an expert witness on the Bible, but with the intent to publicly humiliate him in front of the locals who looked upon Bryan as a hero.

In the end, the defense got the conviction that its evidence could not support.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Image: “Tennessee v. John T. Scopes Trial- Outdoor proceedings on July 20, 1925, showing William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow” by Smithsonian Institution on Wikimedia Commons