Editor’s Note: The following article was originally published by the Observatory of University Ethics on April 22, 2025. The Observatory translated it into English from French. I have edited it, to the best of my ability, to align with Minding the Campus’s style guidelines. It is crossposted here with permission.

We read the remarkable work of Samuel Fitoussi, Why Intellectuals Are Wrong, which has just been published by Éditions de l’Observatoire. The title is provocative, but it is neither a populist pamphlet nor a sweeping indictment. On the contrary, Fitoussi delivers a rigorous reflection, informed by social sciences, the history of ideas, and cognitive psychology, to describe the mechanisms that can lead brilliant minds to adopt false, absurd, or totalitarian ideas. A rich and fascinating essay, from which we publish some excerpts here.

The Bankruptcy of the Intelligentsia in the 20th Century (excerpt from the introduction)

What if culture, intelligence, and education were not a guarantee of wisdom, but actually predisposed one to error? In the USSR, university graduates were two to three times more likely than high school graduates to support the Communist Party. Managers were much more supportive of communist ideology than agricultural workers and semi-skilled workers. In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, responsible for the deaths of nearly two million of their fellow citizens, were led by eight French-speaking intellectuals: five teachers, a university professor, a civil servant, and an economist. All had studied in France in the 1950s, notably at the Sorbonne, where they had absorbed Sartre’s thinking on commitment and necessary violence.

In the West, many leading intellectuals acted as fellow travelers of the Soviet regime, from Jean-Paul Sartre— “A revolutionary regime must get rid of a certain number of individuals who threaten it, and I see no other way than death. One can always get out of prison”—to Bertolt Brecht—on the subject of those shot at the Moscow trials: “The more innocent they are, the more they deserve to be shot”—or Bernard Shaw—”Stalin will be rehabilitated by posterity, as were Voltaire and George Washington”—passing through Althusser, Aragon, André Glucksmann, Edgar Morin, Noam Chomsky…On his return from the Spanish Civil War, George Orwell failed to have the story of the purges, torture and executions committed by the Spanish Communist Party published in influential journals because of the tacit support of the British intelligentsia for communism. It then took a long time, for the same reasons, to find a publisher for his anti-totalitarian satire. Animal Farm—the poet TS Eliot, director of a major publishing house, rejected the manuscript, reproaching Orwell for not presenting the “Trotskyist point of view” with sufficient benevolence. “The English intelligentsia,” Orwell wrote in the preface to the book, which was finally published, “has developed a nationalist loyalty to the USSR, and deep down feels that to question Stalin’s wisdom is a form of blasphemy.” In the 1930s, on the other side of the Atlantic, Ayn Rand experienced a similar misfortune. The young woman, who had fled post-revolutionary Russia for the United States, wrote a novel—We the Living—about daily life under the Bolshevik regime. For three years, she encountered rejections from New York publishers on ideological grounds: “It’s an excellent book,” her agent reassured her. “The problem, of course, is that it has an anti-communist tone. And most American publishers lean toward Trotskyism.”

As for Nazism, supported by Martin Heidegger and Carl Schmitt, it was within the German intellectual elite that it aroused the most enthusiasm.

During his rise to power, historian Paul Johnson recounts, Hitler consistently enjoyed the greatest success on campus, his popularity among students exceeding his ratings among the German population as a whole. He consistently scored highly among teachers and university professors. Many intellectuals were drawn to the upper echelons of the Nazi Party and participated in the most gruesome excesses of the SS. The four Einsatzgruppen—or mobile killing battalions—which were the vanguard of the Final Solution, had an exceptionally high proportion of university graduates among their officers. Otto Ohlendorf, who commanded Battalion “D”—and which murdered 33 Jews in two days—for example, held degrees from three universities and a doctorate in jurisprudence.

At the Wannsee Conference, more than half the participants held doctorates. In the United Kingdom, Orwell reports, intellectuals “were more mistaken about the course of the war than ordinary people, were more dominated by partisan passions. The average left-wing intellectual, for example, thought that the war was lost in 1940, that the Germans would easily conquer Egypt in 1942, that the Japanese would never be driven out of the territories they had conquered, and that the Anglo-American bombing raids were not affecting Germany at all.” “If British intellectuals had done their work with a little more diligence,” he concludes in another text, “the United Kingdom would have laid down its arms in 1940.”

In fact, this is what Bertrand Russell, arguably one of the most brilliant minds of the 20th century, century, declared in the 1930s: “Great Britain should disarm, and, if Hitler’s soldiers invaded us, we should welcome them friendly, like tourists; they would then lose their stiffness and might find our way of life attractive.” ” In The Betrayal of the Clerics, Julien Benda documents the pre-war intellectuals’ fascination with totalitarianism, how many turned away from the search for truth to become servants of regressive ideologies. The irony: Julien Benda himself, two decades later, justified some of the communist executions in the USSR.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Parisian intelligentsia did not shine with its clairvoyance. Fidel Castro received visits from Agnès Varda—who made a propaganda film comparing him to Gary Cooper—Sartre—who drew sixteen laudatory articles from it for France-Soir—or Simone de Beauvoir—who describes the Cuban dictator as a gifted and benevolent philanthropist. This was not, moreover, the first time she had compromised with totalitarianism. A few years earlier, she had traveled to China. Upon her return, she published a five-hundred-page book glorifying Maoism. “The program applied by the regime,” she analyzed, “is the one that any modern and enlightened government, concerned with the progress of its country, would have adopted.” In China, unlike the West, which is consumed by “conformism” and “individualism,” she wrote, “freedom is a very concrete reality.” The philosopher was outraged by the myth conveyed by the “bourgeois press” that the country was a dictatorship.

Mao’s official function involves only fairly limited attributions. Mao’s personal prestige, his qualities, his competence, however, assure him a preponderant role; in particular, since 1927, he has been the undisputed specialist on peasant questions. But the power he exercises is no more dictatorial than that held, for example, by Roosevelt. The Constitution of the new China makes it impossible for authority to be concentrated in the hands of a single person: the country is led by a team whose members are united by a long common struggle and a close comradeship.

De Beauvoir praised the “inimitable naturalness” of the Great Helmsman and his minister Zhou Enlai “which [came] perhaps from their deep peasant ties—and from the serene modesty of men too involved in the world to worry about their faces.” She insisted: “Powerful or subtle, their faces reveal an extraordinary personality. Not only do they seduce, they inspire a very rare feeling: respect.” As is well known, Mao was responsible for 40 to 80 million deaths, making him arguably the greatest mass murderer in human history.

Two decades later, Sartre acclaimed the Iranian Islamic Revolution—he had previously visited Ayatollah Khomeini twice in exile in Yvelines—as did Michel Foucault, who described with a certain naiveté the progressive policies that he believed the mullahs’ regime would pursue:

By “Islamic government,” no one in Iran means a political regime in which the clergy plays a leadership or supervisory role […] General guidelines can be found in the Quran: Islam values work; no one may be deprived of the fruits of their labor; what should belong to all—water, the subsoil—must not be appropriated by anyone. As for freedoms, they will be respected to the extent that their use does not harm others; minorities will be protected and free to live as they wish, provided they do not harm the majority; between men and women, there will be no inequality of rights, but difference, since there is a difference in nature. As for politics, let decisions be taken by the majority, let leaders be accountable to the people, and let everyone, as provided in the Quran, be able to stand up and demand accountability from the one who governs.

[RELATED: After University, Censorship Looms]

A contempt for the common man? (Excerpt from Chapter 6)

According to Raymond Boudon, intellectuals are attracted by the idea that the ordinary man is a victim of false consciousness, desires the wrong things, and is not truly free or autonomous. This magnifies their role and status: they, unlike him, have emerged from the cave. Boudon mentions many schools of thought that have attracted intellectuals for this reason: psychoanalysis—the subject is the puppet of the unconscious which hides its tricks from him—Marxism—the individual manipulated by bourgeois ideology—Nietzscheism—man is driven by resentment and the will to power, but he does not know it—structuralists—language, systems of meaning, organize and limit thought—criminology—delinquency, the fruit of social determinisms rather than individual responsibility. Roger Scruton notes that the concrete life of citizens is largely absent from the texts of left-wing intellectuals of the second half of the 20th century because they were content to imagine individuals as abstractions traversed by forces in “isms.” “Today, neo-feminism asserts that women, traversed—without knowing it—by patriarchal forces, choose little—the professional sectors they invest in; sociology spreads the idea that members of certain minorities, affected by psychological wounds linked to “systemic racism,” have internalized their inferiority and are not directly responsible for their individual destiny. Due to the success of all these theories, the social sciences can only register against the ordinary man: they must re-educate him, teach him to be happy, to make good use of his freedom, to escape the forces that condition him and give him the illusion of being an autonomous subject. They cannot appreciate the ordinary man for what he is, but fantasize the idea of what he should be. “The human sciences,” writes Boudon, “have come to be considered […] as obeying a principal objective: to flush out and denounce the errors of common sense.” Common sense: a false thought that the intellectual must correct. From this point of view, one can wonder if the “abandonment” of the working classes by the left was not inevitable: intellectuals nourished by the social sciences cannot be satisfied with promoting the public policies desired by the working classes: they must rather teach them what they really want, or what they should want if they were not brainwashed—by bourgeois ideology, or, more prosaically, by the 24-hour news channels. In other words, the intellectual adhering to one of the theories of false consciousness cannot agree with the ordinary man, unless he recognizes that he himself is brainwashed.

In fact, many communist or left-wing intellectuals and leaders did not hide their contempt for the workers they set themselves up to represent. “The vanguard group [the Marxist intellectuals] is ideologically more advanced than the masses,” wrote Che Guevara, for example. “The masses only see things half-heartedly and must be incited [to behave in the right way] and subjected to pressure. The dictatorship of the proletariat must be exercised over the defeated class, but also over every individual of the victorious class.” In 1867, Engels, furious that factory workers were not voting left enough, wrote to Marx: “Once again the English proletariat has dishonored itself.” A century later, Hungarian communist leader János Kadar spoke before his country’s parliament: “The task of leaders is not to carry out the will and desires of the masses. It is to fulfill the interests of the masses. Why make a difference between the will and interests of the masses? In the past, we have seen some workers act against their interests.” As for Simone de Beauvoir, she considered it “necessary” to ban the opposition press in China, believing that ideological pluralism could cause confusion for the people, who were too stupid to show discernment: “To propose contradictory theses to the public, as long as they do not have the necessary basis to judge for themselves, is to throw them into confusion.” “Only a “directed” knowledge, she added, is capable of dispelling the darkness. Led by whom? Only by those capable of “dispelling the darkness,” i.e., those ideologically approved by de Beauvoir: for example, Fidel Castro, Mao Zedong, and Joseph Stalin. A few years earlier, the socialist George Bernard Shaw described his contemporaries as “detestable” people whose extermination he “impatiently awaited.” “I would despair,” he confessed, “but for the comforting thought that they are all going to die.” George Orwell humorously recounts his “feeling of horror” when he first attended a Labour Party meeting in the 1930s and met the members, “mean little creatures.” Each one, he writes, “bore the worst stigmata of haughty middle-class superiority. If a real worker, a miner still covered in pit dirt, for instance, had walked in among them, they would have been embarrassed, angry, and disgusted; some, I think, would have run away holding their noses.”

According to Boudon, the success of various theories of false consciousness explains why intellectuals dislike liberalism. Indeed, liberal philosophy is based on the idea that individuals are autonomous and responsible adults, whose choices and desires have intrinsic legitimacy. From this point of view, there is no reason to take away an adult’s freedom of choice and place it in the hands of another adult. On the other hand, if we believe that citizens are blind, hiding in the darkness of the cave, and that an enlightened elite has access to knowledge inaccessible to ordinary mortals, it is normal to hope that this elite will impose its normativity on the entire population. Those who know what constitutes a good life must hold the hand of those who do not know it, nurture them, save them from the misuse of their freedom. This is also an explanation for the hostility of intellectuals to market mechanisms, which encourage businesses to produce goods and services that appeal to citizens—i.e., those on which they are willing to spend their money. In a market economy, the evolution of society is largely the result of the preferences of the masses, not the elite. When an intellectual asserts that an economic sector must be protected from the market and governed by a system of subsidies—or dominated by a public monopoly—he may be expressing his distrust of the tastes of the common man, whom he wants to force to finance the inclinations of the intelligentsia.

If we take the logic of false consciousness to its conclusion, we have another way of understanding the tyranophilia of intellectuals. Indeed, more than a questioning of liberalism, the “suspicion of principle” against common sense, writes Boudon, “inevitably leads to a questioning of democracy.”

[RELATED: History of Communism]

Is youth passing? (Excerpt from Chapter 5)

A reassuring idea is that students, at all times, are enthusiastic about absurd ideas, but that with age and entry into working life, reason takes over. Youth passes. This idea is naive for several reasons.

First, it assumes that the future will resemble the past—or, more precisely, that the dynamics observed during the 1960s-1980s in the Latin Quarter will be reproduced identically.

Then, she forgets that the enthusiasms of youth, before being abandoned, sometimes cause damage. It is said that the Maoist fever of Saint-Germain-des-Prés had no consequences and ended up tiring, but we forget that the Maoist fever of the Chinese students, who massively joined the Red Guards to “purify” their society, killed millions of people. The Maoist fever of Peruvian youth led to the creation of the terrorist movement “Shining Path,” which waged one of the most violent guerrilla wars in history. The result: a civil war and 70 deaths. The movement was led by university professors, and the bulk of its troops were students. It could also be recalled that in the 1930s, Nazi ideas were hegemonic at the university before finding a political translation, that the anthem of Italian fascism was “Gionivezza! Gionivezza!” (Youth! Youth!), or that, a few decades later in Italy, the Marxist-Leninist movement of the Red Brigades, responsible for hundreds of terrorist attacks, was led by sociology students.

Finally, let us note that what, in the West, allowed student ideological fevers to dissipate may no longer be relevant today: ideological diversity after university. As has been said, the absence of pluralism favors the victory of irrationality. In addition to generating a reinforcement of certainties—and therefore vulnerability to bias—it increases the individual cost of deviance. The less pluralism there is in a community, the more the individual who deviates ideologically will find himself socially isolated. Consequently, without ideological diversity, the forces of social rationality prevail over those of epistemic rationality. However, Anchrit Wille and Mark Bovens show that in recent decades, a social, professional, and geographical divide has widened in the West between graduates and non-graduates. These two worlds no longer coexist. In France, whereas previously the right/left divide cut across social classes, voting now closely coincides with a sociological and geographical fault line: educated urbanites vote left—especially for the PS and EELV—the suburbs very left—especially for LFI—and “peripheral” France right or very right—especially for the RN. In the Netherlands, 85 percent of marriages are between spouses with almost the same level of education, and only two in a thousand marriages are between a university graduate and a partner with only primary qualifications. The phenomenon seems to be general in the West: in the past, most people found love close to home. With the democratization of secondary education, associated with greater student mobility and the rise of the Internet, affinities are no longer based on identification with the same geographical community but with the same intellectual status, measured by the level of education. Civil society is no longer a space for social mixing: while in the past, unions, the Church, and parties attracted members from all segments of society, the new associations, focused mainly on ideological issues, recruit exclusively from the highly educated middle and upper classes.

In short, due to the expansion of higher education, graduates can now live without mixing with non-graduates, that is, without ever interacting with individuals capable of counterbalancing their biases. A situation aggravated by the fact that among graduates, ideological homogeneity is increasingly strong. Eric Kaufmann shows, for example, that in the United States, in sectors where graduates have always made up the majority of employees—technology, finance, law, engineering—there was almost perfect parity between left-wing and right-wing employees in 1980, but today, the latter are two to four times less numerous. Now, bad ideas from academia bounce around in a vacuum within a population that is won over to them. Note that the more qualified one is, the more marked the isolation: the probability of educational homogamy—the fact of only mixing with people as qualified as oneself—increases significantly with the level of education, so much so that the ultra-qualified constitute the group which exhibits the highest level of “social closure.” The highly qualified, even after their studies, are therefore those who are least often confronted with divergent opinions. And therefore those who evolve in the conditions least favorable to the development of rational thought. Obviously, if graduates no longer associate with non-graduates, the converse is true. But one can imagine that non-graduates are exposed to the ideas and arguments of graduates—their beliefs constitute the cultural background noise of a society, via the media, advertising, cinema, political speeches—while the reverse is not true.

According to Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, confirmation bias is a modality of human nature that should not, in itself, worry us too much. If everyone uses their cognitive abilities to amass marbles in favor of their ideas, it does not matter as long as a contradictory debate eventually takes place. The researchers point out that human reason was shaped by evolution in a context of small human communities, where disagreements, when they arose, were immediately discussed. Thus, each party arrived with their arguments, and through the game of contradictory exchange, the one with the weakest arguments conceded defeat. Confirmation bias allowed for a “division of cognitive labor.” For example, rather than Thomas and Paul each studying the costs and benefits of a defense strategy against a rival tribe, Thomas—in favor of the strategy—reflected on the benefits, Paul—against—on the costs; this was followed, through debate, by a pooling of work. Today, these same mental mechanisms operate, but Paul—graduate—no longer interacts with Thomas—non-graduate: the pooling never takes place, we are no longer confronted with opposing arguments, and everyone—especially Paul—is stuck in an eternal loop of self-confirmation. In the United States, a recent survey revealed that the more years a progressive had spent in university, the less able he was to understand and reproduce the arguments of conservatives. Why? Because the more educated he was, the fewer right-wing friends he had.

Things to do (Excerpt from the conclusion)

Not only are the elite and intellectuals not immune to ideological misguidedness, but they may be the first to succumb to it. Because the problem is inherent in human nature, it seems difficult to resolve. What can be done? The most important thing is undoubtedly to become aware of this fragility, to keep in mind that we can, with a fearsomely good conscience, rush down a path that leads straight to disaster. “Too many events have revealed the precariousness of what we call civilization,” wrote Raymond Aron. “The most seemingly assured acquisitions have been sacrificed to collective mythologies.” Orwell reminded us that the worst is always possible, that things can change quickly: “Before you say that the prospect of a totalitarian world is a nightmare that will never become reality, remember that in 1925 we would have judged the world of 1942 to be a nightmare that would never become reality.” Indeed, evil can triumph, entire civilizations—even though populated by human beings sharing the same human nature as ours—have been engulfed in obscurantism for centuries—some still are. However, when evil triumphs, it is never as evil: for the Taliban, we are darkness and they are light.

From this point of view, we must undoubtedly cultivate a form of humility in the present. Let us remember that throughout history, most of the errors that have had serious consequences were initially a matter of consensus, or at the very least, were enthusiastically supported by a section of the population convinced that they were defending progress. What we can do, therefore, is to avoid rolling out the red carpet for beliefs, whatever they are, so as to avoid rolling out the red carpet for error disguised as truth, for evil camouflaged as good. Not to put scientific research at the service of a cause. Not to subsidize the “good” ideology, or in any case, not only that one. Do not abandon freedom of expression, especially the freedom to express opinions that run counter to the accepted consensus. Do not allow a single way of thinking to prevail within institutions whose members have the power to impose their norms on the rest of society. Do not censor information that could fuel the “bad” narrative. In short, we can avoid accelerating down the path of error, avoid turning the path into a slope. “Neither intelligence nor the intention to do good can protect us from evil,” wrote Revel. “The only barrier to murderous fanaticism is to live in a pluralistic society where the institutional counterweight of other doctrines and other powers always prevents us from following our own through to the end.” To prevent the victory of evil, we must ensure that there is always a counterbalance to good; to prevent the victory of lies, that there is always a counterbalance to truth.

And that is why we should not legislate against absurd ideas, against disinformation, hatred, or conspiracy theories.

This may seem counterintuitive, but let’s first note that the fight against disinformation is in any case powerless against the most dangerous fake news: that of the elite and intellectuals. Why? Because, as we said in Chapter 8, the elite’s errors are rarely, at least rarely in the present, considered errors—and therefore rarely fought—since it is the elite itself that defines what is error or truth. Now a conspiracy theory considered as a conspiracy theory, and which we sneer at, will always be less harmful than a conspiracy theory that is a consensus among the elite, and which is therefore never defined as such. Similarly, fake news designated as fake news is less dangerous than a false idea to which the elite adheres. And even hate speech, if deemed legitimate by the elite, is justified, rationalized, and not only ceases to be considered hate speech, but can find a political translation. More broadly, those who fight “conspiracy theories,” “hate,” “disinformation,” because they focus, by definition, on the speeches considered Conspiracy theorists, hateful, or fake, run the risk of only waging the battle on the least threatening fronts, where a partial victory has already been achieved, and of losing interest in fronts where a defeat has already been recorded. Indeed, victorious conspiracy theories do not fall within the scope of the fight against conspiracy theories; victorious fake news does not fall within the scope of the fight against fake news, etc. We can also put forward the following hypothesis: the fight against conspiracy theories and fake news, because it engenders, in those who lead it, a self-satisfied good conscience accompanied by the certainty of being on the side of the truth, has the perverse effect of encouraging trust in everything that Is not labeled conspiracy theorists or liars, and thus increase the porosity of our societies to fake news and the most dangerous conspiracy theories. In fact, in a large study carried out on 4 Americans, the more an individual moralized the importance of the fight against disinformation and publicly celebrated his supposed rationality, his supposed attachment to facts and the principles of logic, the more likely he was to share partisan disinformation himself, to attack his ideological opponents in bad faith. Conversely, the individuals who were least likely to succumb to fake news were those who demonstrated intellectual humility, recognized that their intuitions were fallible and that they could be wrong.

Not only do we never legislate against errors with the most serious consequences, but we also run the risk of attacking the truth. For a long time, the elite were certain that the Sun revolved around the Earth, and that a virgin named Mary gave birth to the son of God. Combating disinformation, therefore, meant preventing Copernicus and Galileo from expressing themselves—and indeed, this was tried—or censoring certain Enlightenment philosophers. In the 19th century, the fight against fake news reportedly targeted the Hungarian physician Ignatius Semmelweis, who claimed that handwashing reduced the transmission of disease in hospitals—in fact, his ideas were violently rejected; he was eventually interned and died in unclear circumstances. At the beginning of the 20th century, the fight reportedly targeted the Dreyfusards, a large minority in France. Or Alfred Wegener, who proposed an innovative theory—continental drift—that the scientific community rejected. In the second half of the century, the war against disinformation would have targeted intellectuals who blamed the Katyn massacres on communists rather than the Nazis, or Simon Leys, who described the reality of Maoism—we recall that Le Monde called him a “charlatan” while praising those who sang the praises of the Cultural Revolution. “Mao Zedong liberated his people socially and politically,” the newspaper still wrote at the end of 1974. In a way, it is the right to propagate information considered false in the frame of reference of their time that allows progress: without this freedom, no consensus could ever be shaken. Even the fight against “hate” speech can have perverse effects, hatred being difficult to define objectively. From 1933 to 1938, Winston Churchill was banned from speaking on British radio—of which the BBC held the monopoly—because his anti-Nazi speech was considered alarmist and belligerent. We could obviously multiply the examples. In other words, in all eras, the fight against harmful speech was, or would have been, the ally of the most harmful errors, those of the elite. Again, let us remember that throughout history, the village idiot has generated fewer disasters than those who mocked the village idiot.

From the past, unfortunately, we draw the wrong lessons, drawing from the retrospective condemnation of evil a legitimization of the narcissism of our time rather than a distrust of our ability to confuse lies with truth. We mistakenly believe that good and evil are as easily discernible in the present as they are when looking back, once history has been written. And from this illusion, we derive a sense of moral and intellectual superiority that, in the present, inoculates us against doubt. Perhaps this is why, as Nicolas Gómez Dávila puts it, “no one despises yesterday’s stupidity as much as today’s idiot.” The idea that intellectual elites could serve society by imposing their criteria of truth on the entire population—but, this time, the right criteria—is an idea that wrongly assumes the superiority of intellectuals of the present over those of the past, ignores human nature, and forgets that neither intelligence, nor membership in the elite, nor the will to combat error protect against error.

For insights on higher education worldwide, explore our Minding the World column, offering news, op-eds, and analysis.

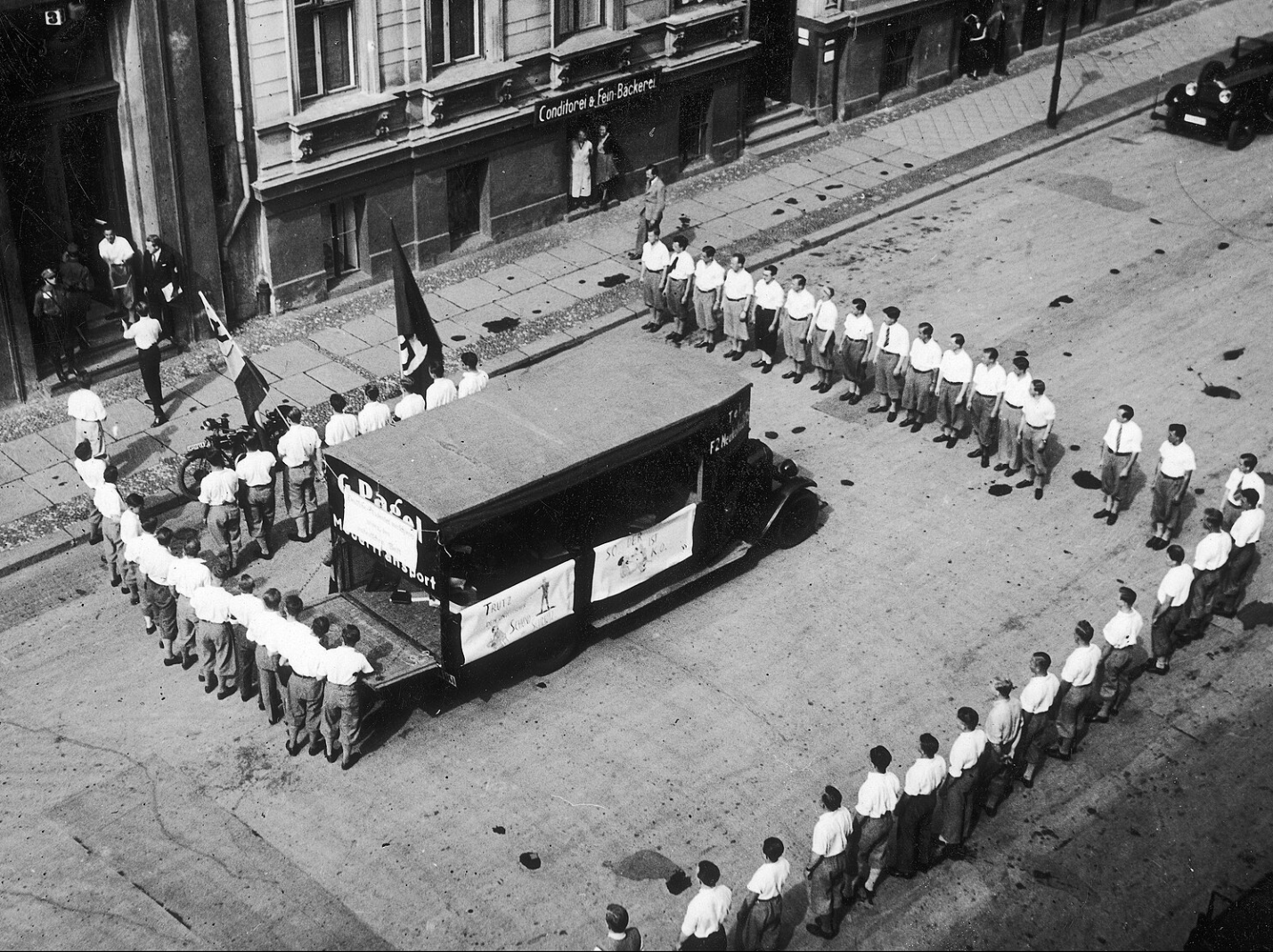

“Photo taken during the nation-wide “Action against un-German Spirit” (German: Aktion wider den undeutschen Geist), conducted by the German Student Union” on Wikimedia Commons

In case it is not clear — it may not be from what I dashed out — the “losers” I refer to are the intellectuals (or “intellectuals”) like Sartre, Chomsky, Russell who were apologists and even promoters of Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and in other cases of the Nazis. I am not referring to this “Collective” of authors as the losers.

As for the “intellectuals” vs. the scientific heroes, there is not comparison between their achievements, nor between their judgment (with a lot of variation).

There is something about science that helps to keep people prett well grounded in reality. Maybe it would be good if most students were compelled to study more natural science, in a somewhat more serious way.

I would take the scientists who were involved with the Manhattan Project over the losers in this article. I would take Copernicus, and Galileo, mentioned in the article. And the other originators of the Scientific Revolution.

Can you explain more?

Yes, particularly since it was SCIENCE that gave the world Eugenics a century ago, which the Nazis then adopted.

I don’t consider eugenics as having been much of an element of the Scientific Revolution. Certainly, none of the people I mentioned were involved in that. But I will claim that if you weigh the sins of “scientific eugencis” against all the good that has been done by Science – the human welfare and health, not to say the magnificent expansion of human understanding — I would claim that there is not remotely a comparison.

Sorry Jonathan, but the “Scientists” of American academia a century ago were all members of the Eugenics Movement.

And yes, science has done good — but it also has been very, VERY wrong at times.

It was science that told us to line our iron water pipes with lead so as to avoid rusty water, it was science that put lead and mercury into paint and arsenic (to control algae) in the lakes that provided our drinking water. It was science that gave us DDT and Thalidomide, Asbestos and Agar.

But for the Manhattan Project, the nuts in Iran wouldn’t be our concern.