Author’s Note: July 2025 will mark the centenary of the famous Tennessee “Scopes Monkey Trial.” This is the third article in a series leading up to the centennial events in Dayton, Tennessee, the site of the trial. Read the first in the series here and the second here.

In the 1925 Dayton Monkey Trial, it was not John Scopes who was in the dock. It was Tennessee’s Butler Act, which forbade the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

Both prosecution and defense wanted Scopes to be convicted, but for different reasons. The defense sought a conviction so that it could appeal the case on First Amendment grounds and have the Butler Act overturned. The prosecution wanted a conviction to affirm the Butler Act. In a previous article, I outlined the strengths and weaknesses of the defense’s case. What of the prosecutions?

The prosecution team consisted of Tom Stewart, who was state’s attorney for the Rhea County circuit; Gordon McKenzie, a local attorney and anti-evolution activist, Herbert and Sue Hicks, who were friends with Scopes and part of the group that recruited Scopes to be the defendant; and most prominently, William Jennings Bryan. Bryan’s son, William Jr, also aided the prosecution.

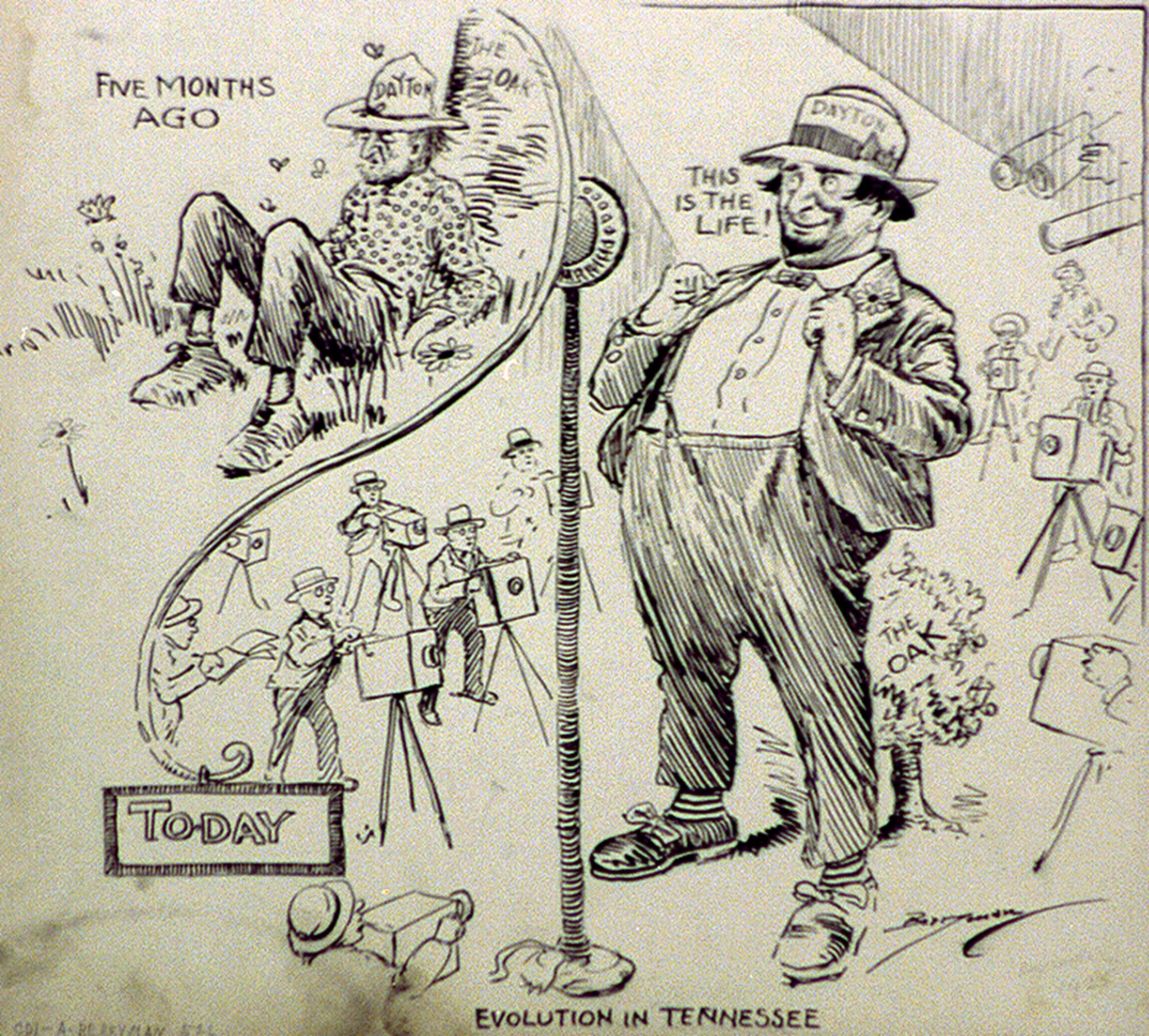

Where the defense’s case was weak, the prosecution’s case was weaker, with the biggest weakness being that Scopes’ “offense” was a put-up job. Scopes had been recruited by the Dayton town “boomers”—as Mencken called them—to be the convenient show defendant for the test case the boomers hoped would bring attention and commerce to their placid town. This was no secret cabal: their motivations were well-known and widely lampooned (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution in Tennessee. Editorial cartoon by Clifford Kennedy Berryman, probably for the Washington Evening Star (Library of Congress).

Scopes had been acting as a substitute teacher and coach at the high school. He mostly taught geology and chemistry. He was teaching biology that spring only by accident, filling in for the regular biology teacher who was out sick. After the term ended, he stayed on in Dayton mostly because he had nothing better to do that summer. In his memoir The Center of the Storm, Scopes said he had stayed to attend a summer dance, where he’d hoped to meet a girl he had taken a fancy to. He never even kissed her, he later recalled.

[RELATED: WATCH: Why Scientists Aren’t Really Leaving—and Why Chimps Aren’t 99% Human]

Here is where the logic of the Scopes case becomes twisted. The town boomers, Scopes himself, and the defense team sought to overturn the Butler Act on appeal. Once Scopes was charged, though, the prosecution was obliged to seek a conviction so the Butler Act could be upheld. Tom Stewart, the state’s attorney, thus had to focus the prosecution’s strategy on the narrow question of whether Scopes had violated the Butler Act. He faced an uphill battle in doing so.

Scopes himself could not be compelled to admit teaching evolution, of course. In any event, the defense team had made it emphatically clear to Scopes that his role was to sit at the defense table and keep his mouth shut. To establish Scopes’s guilt, the prosecution had to rely on testimony that Scopes had taught evolution to his students, or had admitted that he had. Walter White, the superintendent of the Dayton schools, was called to testify that Scopes had admitted teaching evolution when they met at Robinson’s drugstore to recruit Scopes. By all accounts, the conversation that day had actually turned on whether the state-approved biology textbook, George William Hunter’s A Civic Biology, could be used without violating the Butler Act. So, White’s testimony was, at best, a shade off the truth. In any event, by his own recollection, Scopes “wasn’t sure I had taught evolution.”

Testimony from Scopes’s students could have provided first-hand evidence that Scopes had, in fact, taught evolution. The prosecution, therefore, lined up four students who had been in Scopes’s classroom and could serve as direct witnesses to what Scopes had taught. Their answers were what one would expect from teenage boys: vague, off point, wandering into irrelevancies, and the defense made short work of their testimony. In the end, the prosecution did not call the other two students to the stand.

Had not the defense been so determined to win a conviction, Scopes likely would have been acquitted on the evidence presented by the prosecution. Even if Scopes had taught evolution, he had only done so from a textbook that was mandated by the State of Tennessee, something for which he could hardly be held culpable.

[RELATED: The Evolution of Intelligent Design Theory]

If the prosecution’s case was so weak on its merits, it did have one card up its sleeve that the defense did not: William Jennings Bryan, the Prairie Populist, the Great Commoner. Unlike the defense, Bryan had his finger on the cultural anxieties of the South and the deeper cultural conflict that simmered beneath the popular anti-evolution movements in Tennessee and throughout the South. Bryan played this card masterfully, framing the case as a test for who gets to educate their children? Bryan’s zealous defense of biblical literalism was window dressing for the real issue in the case. Who got to say how the children of Tennessee were to be taught in their schools? The people of Tennessee? Or outsiders coming in and telling the people of Tennessee what they were allowed to think and teach? To quote from Bryan’s closing statement:

if the people of Tennessee were to go·into a state like New York – the one from which this impulse comes to resist this law, or go into any state – if they went into any state and tried to convince the people that a law they had passed ought not to be enforced, just because the people who went there didn’t think it ought to have been passed, don’t you think it would be resented as an impertinence?

Ultimately, it was Bryan’s defense of local autonomy and civic pride that secured the guilty verdict. Not the prosecution’s flimsy evidence, nor the defense’s histrionic deflections, but his powerful defense of populism. This should prompt a rethink of the myth that has been spun about Bryan since the Scopes trial, aided in no small part by agitprop spectacles like Inherit the Wind. Bryan was not the blundering, buffoonish, has-been glutton that Darrow easily ran rings around and humiliated. To the contrary, he was the master of the trial.

With the guilty verdict rendered, Judge Raulston fined John Scopes $100, with a $2,000 bond in anticipation of the appeal. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) paid the fine, and the Baltimore Sun covered the bond. That marked the end of John Scopes’s career as a celebrity defendant, who went on to live a quiet and admirable life.

While the state and defense got the guilty verdict they both desired, it was the State of Tennessee that had the last laugh. A year later, the Tennessee Supreme Court threw out the conviction on the grounds that it was the jury, not the judge, who had to set Scopes’ sentence. The ACLU lost its dream case, and the Butler Act remained on the books for another forty-two years.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

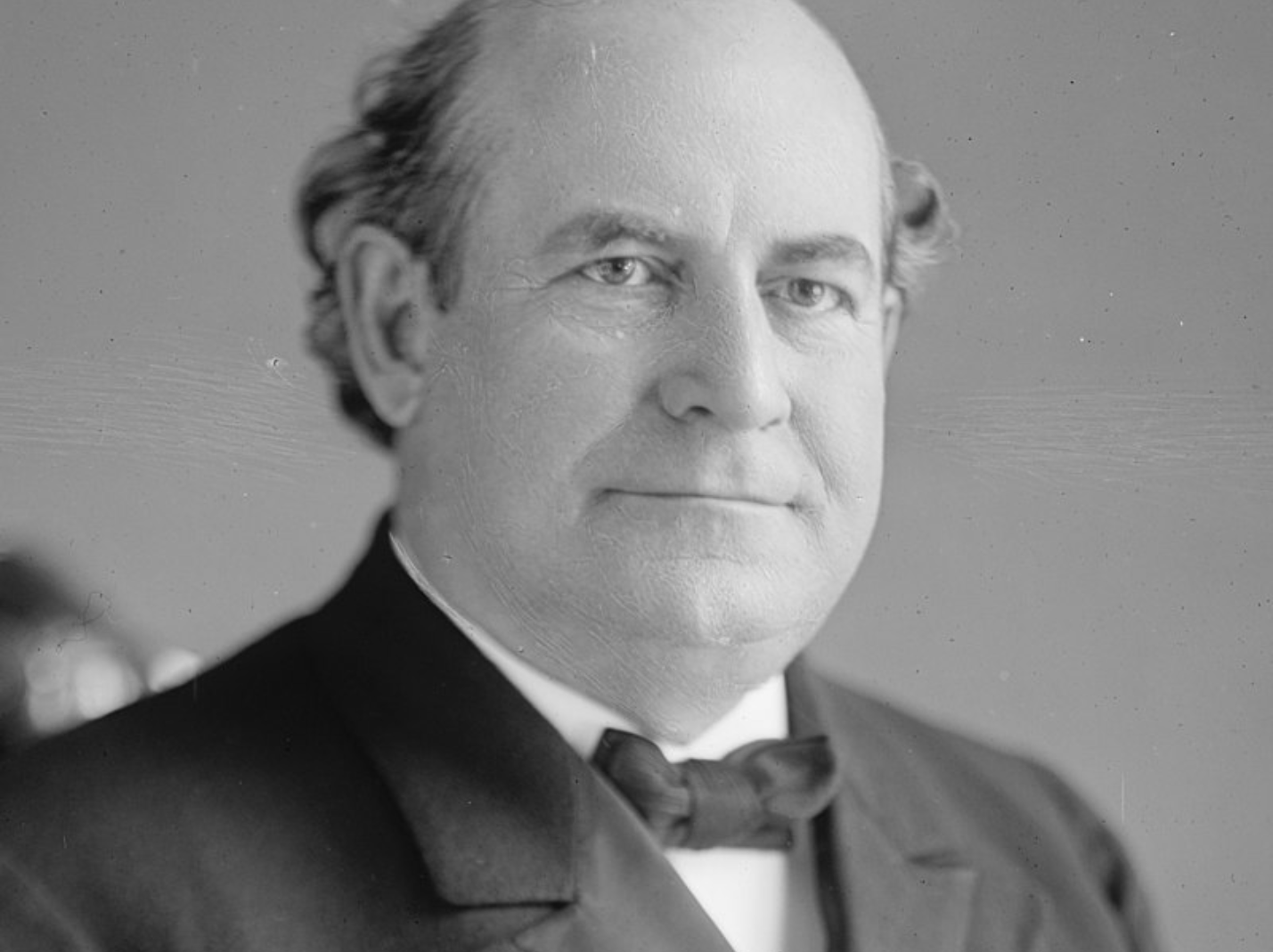

Image: “BRYAN, WILLIAM JENNINGS” by Harris & Ewing on Wikipedia