July 2025 will mark the centenary of the famous Tennessee “Scopes monkey trial.” This is the fourth and last article in a series leading up to the centennial events in Dayton, Tennessee, the site of the trial. Read the first in the series here, the second here, and the third here.

Just what was the Scopes trial about?

As a legal matter, “not much” would be the best answer. Scopes’s conviction was overturned on a technicality, and his life post-trial went on pretty much unperturbed. The Butler Act that Scopes supposedly violated stayed on the books for another four decades. Neither prosecution nor defense had particularly strong cases to argue, and the trial set no legal precedent. Dayton, Tennessee, went back to the placid small town it had been before.

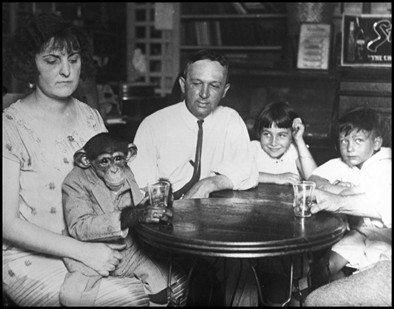

The Scopes trial’s enduring legacy, rather, was a pantomime of an epic confrontation of science versus religion, ginned up by the derring-do performances of Clarence Darrow (science), William Jennings Bryan (religion), and H.L. Mencken (sarcasm). The more apt face of the show would probably have been gentleman chimp Joe Mendi, in Dayton to represent the famous “missing link.” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Joe Mendi, the simian mascot for the Scopes trial, sitting in Robinson’s Drugstore, Dayton, Tennessee, July 1925. Source: Library of Congress.

Puzzling questions lurk behind the curtain, though. Just why was evolution the theme of the Scopes trial? Why not something else, like civics or history? Why was anti-evolutionism a potent political cause in Tennessee, and for that matter, throughout the 1920s South? Was evolutionism in the 1920s really the settled science it claimed to be?

Before proceeding, I would like to share a bit about myself to clarify my motivations. I describe myself as a “heterodox evolutionist.” I am an evolutionist, not a creationist, as I am sometimes accused. Nor am I an apologist for Intelligent Design Theory, as I also am sometimes accused. I describe myself as a heterodox evolutionist because I parted with Darwinian orthodoxy about two decades into my research career. We didn’t part company for any religious reason, but because Darwinism no longer made scientific sense to me. Among the things that drove us apart was the ongoing conflation of evolutionism with Darwinism. The two are not the same: evolutionism is the doctrine that life on Earth has a history, while Darwinism is a doctrine of mechanism. Each poses different scientific questions, and conflating the two has created a substantial space for confusion and misrepresentation. This space is where the Scopes trial pantomime was staged.

At the time of the Scopes trial, evolutionism sat on a pretty solid foundation of evidence from paleontology and geology. In contrast, Darwinism at the time was at a low ebb, a period known as the “eclipse of Darwinism.” The scientific strong horse at the time was Thomas Hunt Morgan’s doctrine of “mutationism” (also known as Morganism), which Morgan claimed to refute the Darwinian doctrine of evolution by natural selection. It was only in the decade following the Scopes trial that Darwinism rose from the grave Morgan had dug for it.

Despite its weakness, Darwinism had become a protean stalking horse for a wide range of cultural, social, and political issues, which provided the seed crystal that precipitated the widespread anti-evolution movement in the South. A hint of those cultural issues is embedded in the title of the textbook Scopes had used in his biology class: George William Hunter’s 1914 book, A Civic Biology. The jarring word here is “civic”.

Civic biology was part of an educational movement aimed at reshaping biology instruction to serve social purposes. Traditionally, biology had been taught as separate courses in zoology and botany. Civic biology sought to integrate those traditional divisions into a single framework, to transform biology education into an instrument for improving “the human world.” A Civic Biology was, in short, biology instruction mobilized to civic action. More to the point, it was biology instruction mobilized to serve the civic interests of the urban and industrialized society of the North, from which civic biology originated.

At the time, the South was making a transition from a largely agrarian culture to an increasingly urban and industrialized one. Along with that came a movement for education reform, spearheaded in Tennessee by Austin Peay, the governor. Tennessee had a long tradition of public schools governed by local school boards, which set their own rules for curricula and compulsory attendance. The modernizers regarded this as holding back the South’s economic development, mainly because it did not suit the modernizers’ biases for increasing industrialization and urbanization. Education reform was their tool to assert state control over the independent and largely rural independent school boards. Control consisted of mandating compulsory education through high school and setting state-standardized curricula that would overrule local school boards. Among these were statewide mandates for textbooks: A Civic Biology was Tennessee’s mandated textbook for biology.

Urban schools in Tennessee largely went along with these reforms, but rural schools were a different matter. In those districts, the family was central to socializing children, and the schools were regarded as the vehicle for cementing the family as the primary socializer. Education reform in Tennessee was regarded as usurping the family and replacing it with the state. To quote Adam Shapiro, the “seizure of control of the schools by the state was seen as part of a larger effort to regulate local culture in ways consistent with the ideology embedded in biology education.” The ideology embedded in A Civic Biology was urban, Northern, and progressive in outlook. Rural schools saw education “reform” as the state of Tennessee importing this ideology into local schools, administered through state educational bureaucracies that were likewise urban and progressive.

The Scopes trial was a microcosm of the tensions between urban and state versus rural and local interests. The Dayton town luminaries who recruited John Scopes to be the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) plaintiff were largely drawn from the urban/state side of the divide. Ten of the twelve jurors, on the other hand, were Rhea County farmers, drawn from the rural/local side, and generally skeptical of the State of Tennessee’s attempts to wrest control of education from parents.

In the 1920s, this tension crystallized around anti-evolutionism, prompting the question: Why evolution, and not some other cause? The proximate answer to this question was the persona and reputation of William Jennings Bryan, the long-time champion of populist rural interests over the monied capitalists who were, to paraphrase, intent on crucifying the people on a “cross of gold.” In his 1922 New York Times essay, “God and Evolution,” Bryan asserted that Darwinism was the new “cross of gold” that the monied and progressive interests of the North were imposing on the family-centered culture and traditions of the agrarian South. It was a message that resonated strongly throughout the South, and Bryan’s essay provided the focus.

Bryan’s case against Darwinism was actually stronger than his many contemporary and future critics would grant. Virtually from the date of publication of On the Origin of Species, Darwinism has been enlisted as justification for a vast array of political and social causes, some of them flatly contradictory to one another. For example, Darwinism has been invoked at various times to justify Prussian imperialism, the Bismarckian welfare state and Nazi race ideology. “Social Darwinism” has a similarly protean nature, serving at times as an avatar of free-market capitalism, and at others as justification for socialism and communism, and still at others as justification for indifference to others’ welfare that borders on cruelty.

What specifically concerned Bryan was how adherence to this shape-shifting ideology promoted nihilism. If Darwinism could mean so many things, Bryan argued, it meant nothing at all, leaving in its wake a developing cult of scientism that dethroned God, morality, and religion. Bryan had a point. To draw directly from the cult of Darwinist scientism, eugenics was in its heyday in the 1920s, with many of the consequences falling on poor, Southern, rural whites like Carrie Buck. Eugenics was, at the time, “settled science” propped up by near-unanimous scientific and elite opinion, much like climate science is today, and Darwinian thought was at the center of its rise. At the Scopes trial, it was not “evolution” on trial so much as social upheaval dressed up in Darwinian costume. Malcolm Metcalf, the zoology professor who was the only defense expert witness allowed to testify, was a prominent proponent of eugenics. Among the unifying biological principles in A Civic Biology, eugenics was the tool students could use for the betterment of mankind.

Bryan’s rural followers may not have been conversant with the principles of eugenics or the nuances of evolutionary thought in the 1920s, but they were well aware of the social turmoil that accompanied Darwinian progressivism in their own communities and traditions. Bryan skillfully used Darwinism as the lens to focus those inchoate anxieties into action throughout the South. Thus, it was not ignorance or anti-intellectual bigotry that drove the rise of anti-evolutionism in the 1920s South. To the contrary, it was because the agrarian South was paying attention, and wasn’t liking what it saw.

[RELATED: WATCH: Why Scientists Aren’t Really Leaving—and Why Chimps Aren’t 99% Human]

When the Butler Act was first proposed, it was portrayed as the initiative of a supposedly illiterate farmer, John Washington Butler. It was widely mocked: the Nashville Banner lumped it in with a grab-bag of supposedly doomed and ridiculous bills, including a provision against “suck-egg dogs.” Yet the Butler Act prevailed because it drew support from a broad swathe of public opinion, and not just the Primitive Baptist church that Butler attended. In the Tennessee legislature, the bill garnered support from both rural and urban constituencies, as well as from diverse religious groups that ranged from primitive fundamentalist to high-church Methodism.

This broad support is what persuaded the governor, Austin Peay, to sign the bill into law despite his initial intentions to veto it. He justified his turnaround thus:

Right or wrong, there is a deep and widespread belief that something is shaking the fundamentals of the country, both in religion and morals. It is the opinion of many that an abandonment of the old fashioned faith and belief in the Bible is our trouble in large degree. It is my own belief.

Peay took considerable heat for signing the Butler Act into law, but largely from quarters that did not understand the reasons and rationales behind it. The ACLU and the Northern urban elites it represented cast it as a conflict between religious beliefs and freedom of thought, because they had no other lens through which to view the reasons behind the anti-evolution movement. The people of Tennessee saw another issue at stake: who controls how taxpayers support the education of the young?

Now, a century later, the Scopes trial is timely because it is a concern that has erupted again, this time over another “scientific” issue—transgenderism—that is enveloped in the same scientistic fog that swirled around evolutionism in the 1920s. Now, as then, parental resistance is driven by central authorities seizing control of education from its rightful custodians: parents. Now, as then, this populist movement has left the political and liberal elites of our own day in a state of befuddlement and anger.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Image: “Scopes Trial Museum” by beautifulcataya on Flickr