New Jersey City University (NJCU) recently announced a plan to merge with nearby Kean University. The announcement comes after years of financial mismanagement and shrinking enrollment.

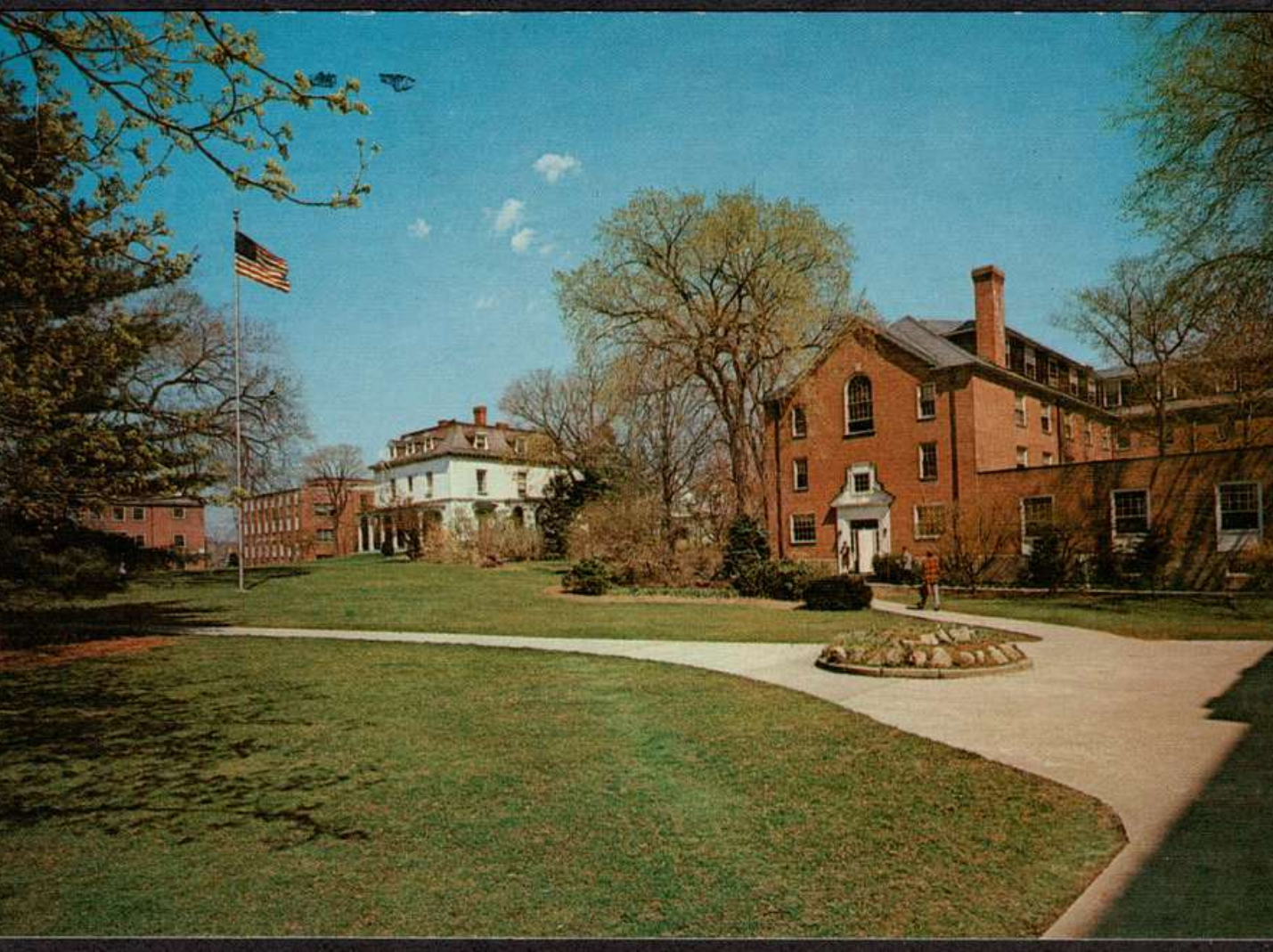

NJCU is lucky. A merger is much better than going out of business outright, a fate that has recently befallen several historic institutions, including Limestone University, which closed after 160 years in operation. Eastern Nazarene College, established in 1900, has also closed, and its campus will be converted into housing.

Since January 2024, more than 30 colleges have closed or merged. Most are small, private nonprofit schools. Small Christian universities are overrepresented. Virtually all saw enrollment decline and debt rise for years before they went under.

And there will be many more.

[RELATED: Closures are Decimating Higher Ed. But Your Campus Needn’t Succumb]

The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia predicts that, in the worst-case scenario, 80 schools could close this year. The late Clayton Christensen warned that 25 percent of universities would dissolve or merge by 2028. The Grim Reaper is moving faster, and Christensen’s prediction may prove correct, just over a longer time frame.

Benjamin Franklin once said, “a great Empire, like a great Cake, is most easily diminished at the Edges.” The American higher education empire should heed his words. The public’s eyes are on Harvard University and Columbia University, while few shed tears for Limestone or Eastern Nazarene. But what is a blip on the national radar can be a devastating loss for a college town. Jobs vanish. Local businesses lose customers. Campuses are abandoned or bulldozed.

When a university dies, a sliver of American culture dies with it.

No one suffers more than students. Some universities are doing the best they can for their former students, but schools like NJCU enroll working adults and first-generation students. When they fold, these students must navigate re-enrollment, credit transfers, and convoluted financial aid. Some will walk away from their education altogether.

Why does this keep happening?

The reasons are complex. Enrollment is declining, driven by demographic shifts and skepticism about the value of a degree. Operating costs continue to rise. Trust in universities is at historic lows. Colleges have used up COVID19-era federal relief funds, and as elite universities face devastating cuts in federal funding, it’s unlikely the current administration will issue any more blank checks.

No longer is higher education insulated from economic downturns.

Prestigious universities can better absorb these shocks. They have massive endowments, diversified revenue streams, and their brand name ensures they will never want for applicants. Most importantly, they can operate even when they are deep in debt. In contrast, smaller schools are accustomed to supplementing their budgets with tuition money and donations. Schools that go into debt can end up in a death spiral: cutting expenses harms enrollment, but bolstering enrollment costs money. If this trend of consolidation is not addressed, the future could be characterized by a handful of too-big-to-fail universities with numerous satellite campuses.

The entire sector must re-evaluate, starting with financial responsibility.

NCJU went from a $108 million budget surplus in 2014 to a $14 million budget deficit. For most schools, this will mean reducing administrative bloat and making painful but necessary cuts to athletics, student life services, and massive capital improvement projects. Colleges must ensure that what matters most—academics—is prioritized on the balance sheet. Resources like the American Council of Trustees and Alumni’s Bold Leadership, Real Reform 2.0 provide best practices for reducing costs while improving student outcomes.

[RELATED: Vedder’s Case for Creative Destruction]

Small schools have one major advantage: they’re nimble. They can introduce new technologies and creative solutions. They can cooperate with other universities by forming consortia and collaborating on curriculum. They can leverage their often-passionate small community by creating alumni networks that advocate for their school and provide job opportunities for recent graduates.

On the government side, federal funds in higher education must be allocated strategically and efficiently. The most obvious way to do this is for Congress to reauthorize the Higher Education Act. The reauthorized HEA would reassert congressional leadership in higher education and allow for more certainty for universities navigating tough financial times.

Above all, college leaders must recognize that the fat years are over. They cannot live in denial, hoping the next enrollment cycle or administration will save them. It may be too late for Limestone and Eastern Nazarene, but there is still time to address this troubling national trend. Universities must make the tough decisions necessary to become and remain solvent. The alternatives are to be absorbed or to cease to be.

Image of Eastern Nazarene College by Thomas Crane Public Library on Picryl

Fall 2026 is when the babies not born in 2008 won’t be going to college,

This fall is when recruitment starts for F-26 and by Christmas, there are going to be a LOT of institutions seeing the writing on the wall…

You ain’t seen nothing yet….