In a recent article, I described how Arizona State University (ASU) refused to investigate plagiarism by its administrator, Sethuraman Panchanathan, while he was serving as director of the National Science Foundation (NSF). Panchanathan later resigned unexpectedly and returned to ASU—just in time for the university to sue the NSF to preserve its high rate of administrative overhead.

The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), one of Panchanathan’s publishers, also refused to investigate. Instead, it issued legal threats and prohibited further discussion of the misconduct by its staff. That leaves the National Science Board (NSB)—the NSF’s official oversight body—to enforce the federal code that prohibits plagiarism (45 CFR § 689).

But the NSB appears unwilling or unable to act.

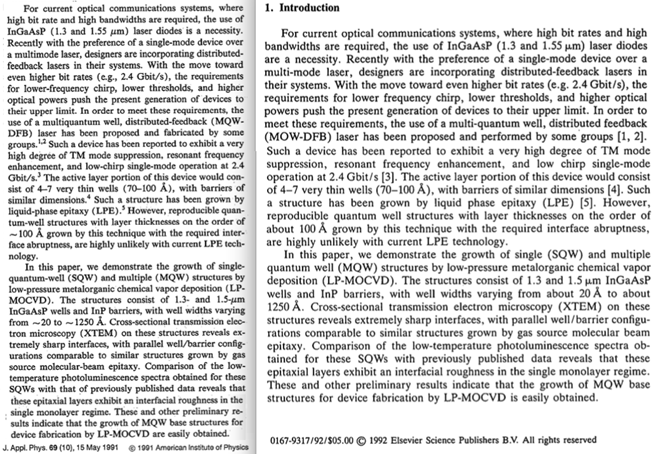

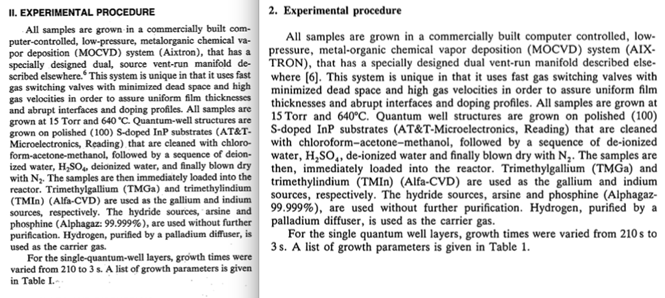

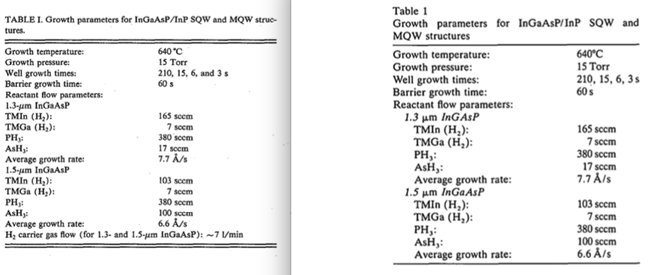

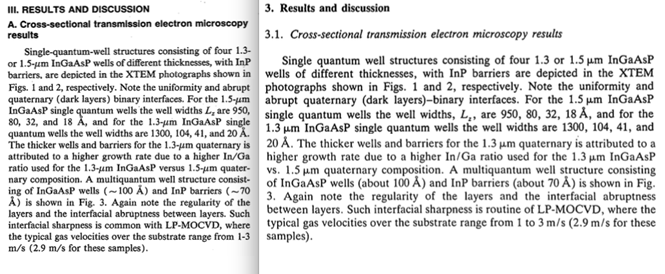

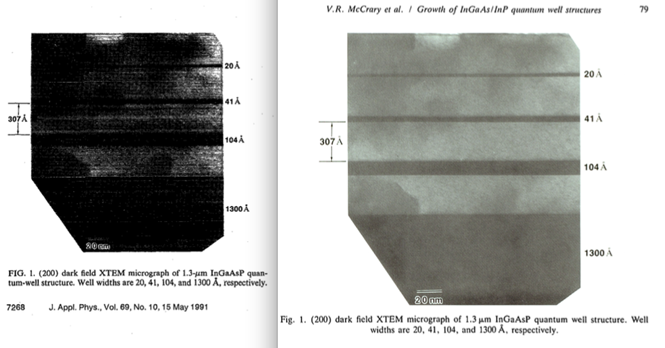

It recently elected Victor R. McCrary as its new chair, despite credible concerns about McCrary’s own publication practices. According to a PubPeer thread, McCrary republished a previously coauthored paper without quotation marks, without citation, and without permission from the copyright holder—the American Institute of Physics. The republished version appeared in a journal published by Elsevier, whose policies clearly define plagiarism as the uncredited or unauthorized reuse of someone else’s work.

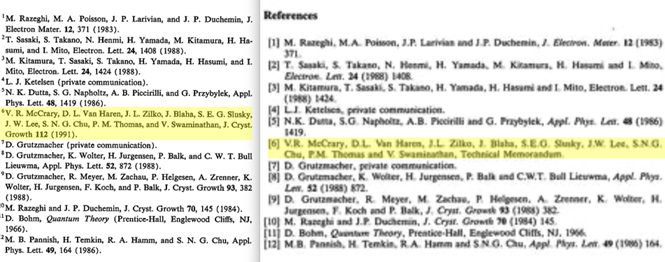

In this case, McCrary duplicated a paper he had coauthored with eight others, then submitted it to a new journal as if it were original. He subtly altered one of the references: in the original paper, reference #6 pointed to another article he had coauthored. In the second version, rather than citing the original paper he was copying, McCrary swapped in a citation to one of his own unpublished technical memos. This gave the impression that the new paper was based on fresh, independent work—discouraging readers and reviewers from noticing the duplication and making the paper appear more original than it actually was.

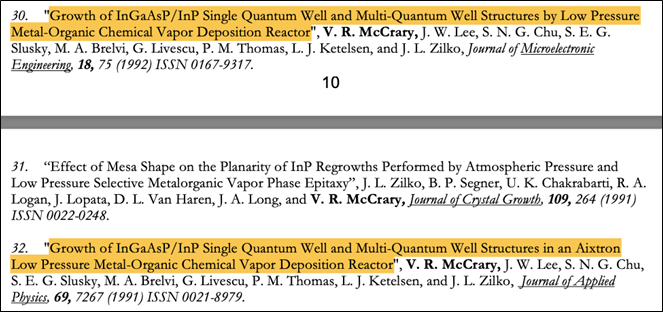

On his résumé, shown in the image below, McCrary listed both papers as if they were distinct research contributions, despite their near-identical content. This created the false impression that he had produced more original work than he actually had. By replacing the original reference in the second paper with a citation to a technical memo, he obscured the duplication—making it harder for reviewers or readers to detect the overlap. The result was an inflated publication count and a misrepresented academic record.

McCrary was appointed to the National Science Board (NSB) by the U.S. President under 42 U.S. Code § 1863. He was later elected chair by fellow board members. It appears the NSB neither reviewed his publication history with plagiarism-detection software nor consulted PubPeer, where this duplication had already been flagged. If so, the Board failed in its oversight responsibilities.

The alternative is worse: the NSB may have known, but accepted that its chair copied the work of eight co-authors—without quotation marks, without attribution, and without permission from the copyright holder—while presenting the paper as original. That would place the NSB in open violation of NSF policy and 45 CFR § 689, which explicitly prohibits plagiarism.

Falsifying credentials in the process of receiving a presidential appointment is plainly unethical. But when it happens in science, there seems to be no mechanism for accountability. Former NSF director Sethuraman Panchanathan used the same strategy repeatedly, yet the NSB cannot condemn his actions without implicating its own chair. The result? A quiet tolerance of academic sleight of hand, where one paper becomes two.

[RELATED: ASU’s Plagiarism Loophole]

This is not a case of “self-plagiarism,” where an author republishes their own work while retaining copyright. McCrary republished a paper coauthored with eight others—without citation, quotation, or permission—and falsely presented it as novel.

That’s not merely academic dishonesty. It resembles fraud. And it almost certainly constitutes a violation of federal copyright law.

Insiders like McCrary and Panchanathan have inflated their publication counts this way for decades, quietly working the system while rising to lead the country’s premier science agency. And because of entrenched interests and institutional complicity, no one is willing to hold them accountable.

In 2024, NSF’s acting director Brian Stone was asked about the problem. He did not respond. To be fair, Stone served under Panchanathan at the time and may not have been in a position to challenge his superior’s publishing record.

I also contacted the White House Presidential Personnel Office to inquire about how NSB members and NSF officials are vetted. As of this writing, they have not responded.

Below is the first set of side-by-side examples from PubPeer, illustrating McCrary’s copy-paste tactics—tactics far more egregious than the “duplicative language without appropriate attribution” that led to the Harvard president’s resignation in 2024.

Image by Nico on Adobe Stock; Asset ID#: 345423902

“…just in time for the university to sue the NSF to preserve its high rate of administrative overhead.”

If we’re talking about administrative overhead for existing—i.e., already issued—research grants, then the university has a case. for future grants this is laughable. If ASU doesn’t like the lower administrative rates, then don’t apply to the NSF for funding. NSF funding is not a right.