Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from an article originally published on Heterodox Stem on July 6, 2025. With some edits to match Minding the Campus’s style guidelines, it is crossposted here with permission.

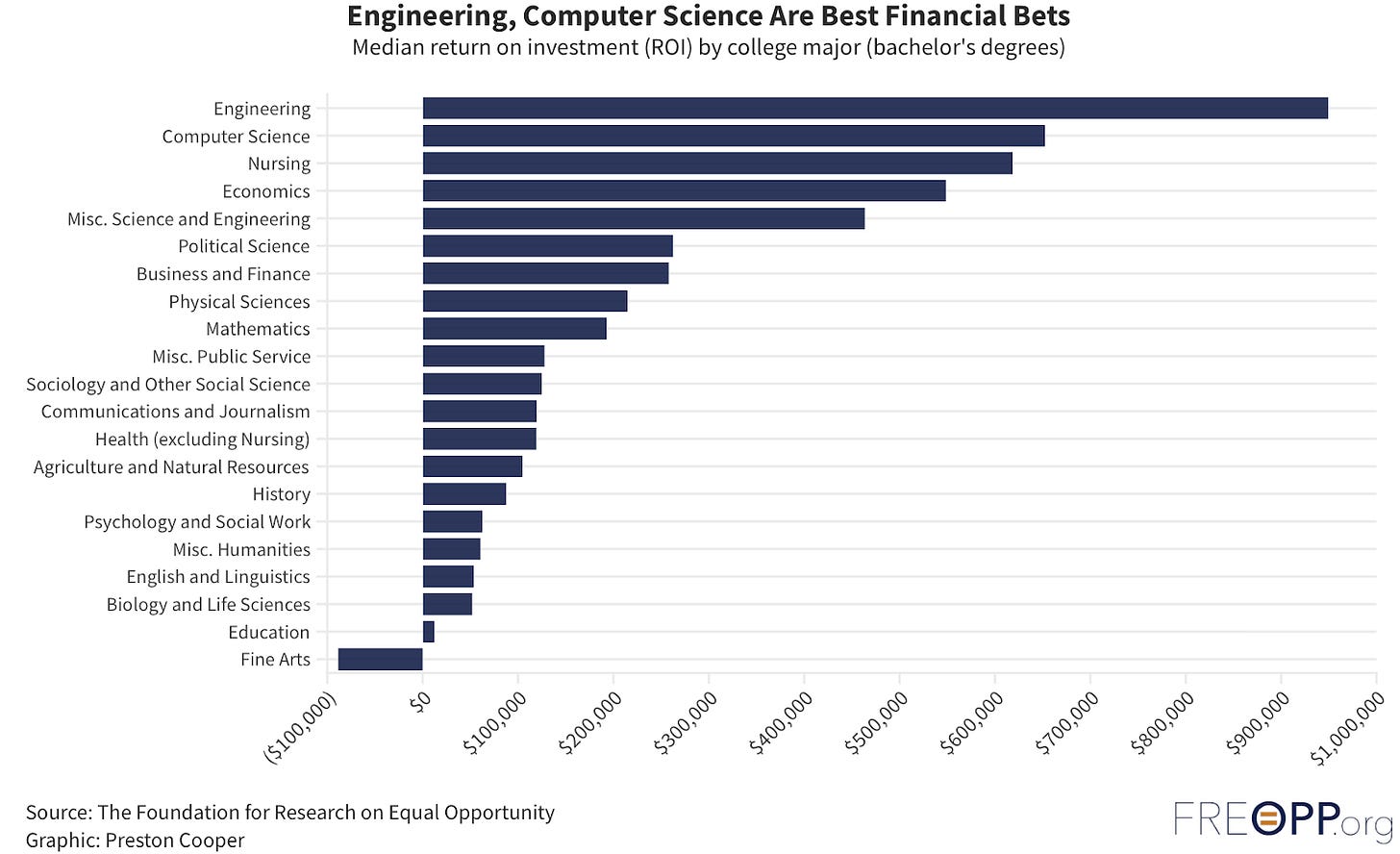

The primary function of universities is to educate skilled labor. Within universities, skills are esteemed mainly by awarded degrees or titles and the prestige of the awarder. Outside universities, skills are esteemed mainly by pay, which in the private sector is tied mostly to economic value added. The most striking evidence of the huge productive/unproductive divide in U.S. tertiary education is the vast difference in discounted net returns—net present value or NPV—on educational investment by field of specialization. Here is a chart of median NPV by college major compiled by the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP) using data from the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard. (While FREOPP calls it ROI, the values correspond to NPV calculated at a three percent real discount rate as excess over the expected non-college alternative).

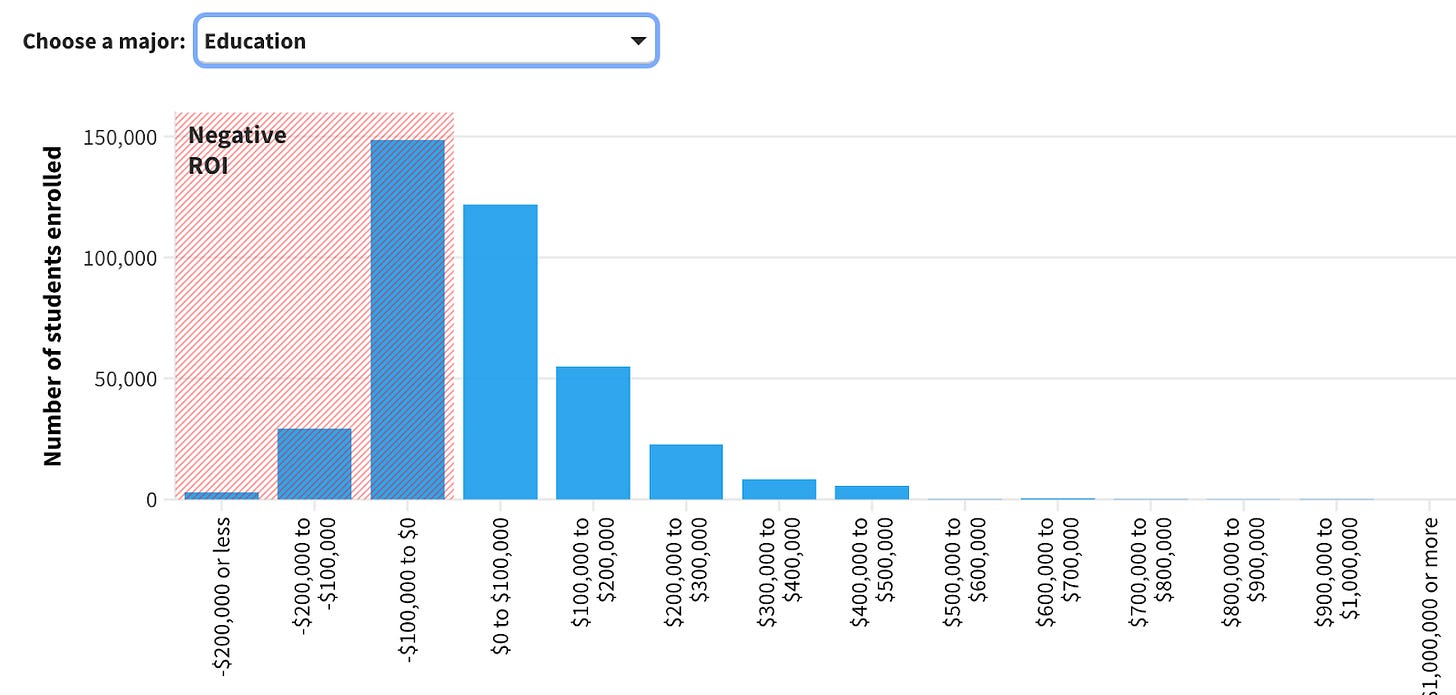

The general pattern is clear. The economy values technical skills in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), as well as medicine and business, far more than it values traditional liberal arts. This extends to blue-collar technical skills, such as vehicle maintenance and repair, precision metalworking, HVAC technology, and electrical and power transmission installation—their median NPV is over $300,000. The differences are even more striking when we take dispersion into account. The mean returns are much higher for technical skills and the odds of negative returns much lower. Here are FREOPP-compiled NPV distributions for BA or BS degrees in engineering and education:

[RELATED: Degrees Have Value—But Employers Shouldn’t Require Them]

Worse, students are disproportionately concentrated in less-valued majors. By FREOPP measures, three in ten undergrads are likely to earn negative financial returns on their investments. Returns to master’s degrees are even more fraught, with 43 percent likely to be negative and 15 percent sacrificing over $200,000. While even the losers may gain non-pecuniary advantages in leisure and satisfaction, the net benefits are concentrated among children from wealthier families who can better subsidize their lifestyles.

Granted, the details reflect past experience that the future will not exactly repeat. For example, low-level computer science jobs are now being squeezed out by artificial intelligence (AI). However, the general trends seem bound to persist and worsen for the following reasons:

- Education is valued partly—or mostly, as economist Bryan Caplan contends—as a signal for intelligence, perseverance, and compliance rather than know-how. While this consideration already favors technical majors given their more demanding curricula, the differential will likely rise now that AI makes it easy to compose the kinds of essays favored in liberal arts.

- Technological progress generally favors technical skilled labor although the skills needed change over time. STEM graduates tend to be particularly versatile, partly because the scientific principles driving one field tend to have analogues in other fields.

- U.S. universities arguably place too little emphasis on STEM, which augurs continued high premia for STEM skills and continued squeezes on liberal arts. According to Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, the share of graduates in 2020 in STEM fields was 20 percent in the U.S. versus 37 percent in Germany and 41 percent in China.

- For a related perspective, the U.S. currently accounts for about 25 percent of global GDP but its colleges and universities supply only about seven to eight percent of STEM grads. Since the U.S. excels at higher levels of STEM, its 15 percent share of global STEM PhDs seems a fairer measure. However, about a third of these were earned by foreign students, so any additional restrictions on skilled immigration will raise the premium for domestic STEM grads.

- The U.S. has an unusually high share of people in peak working ages of 25 to 64 who have college degrees that are not in STEM or health care. According to Google Gemini, the share is 33 percent in the U.S. versus shares a 27 percent OECD average, 18 percent in Germany, nine percent in India, and four percent in China. Hence, many of the careers that new U.S. liberal arts grads seek to enter are relatively saturated with more experienced liberal arts grads. Only Canada, at 39 percent, exceeds the U.S. share, which likely explains some similar tensions.

Of course, new grads in any field bring advantages in youth, energy, and enthusiasm. Furthermore, new grads are more familiar and comfortable with new technologies, which is especially important in this era of unprecedented rapid innovation. Much of their work in business will be highly productive. But most young grads have high expectations, prodded in part by large student debt, and their demand for jobs needing a liberal arts degree greatly exceeds the supply. Naturally, they favor policies inclined to raise their net returns. These include:

- cancellation of student debt.

- more explicit or implicit quotas for female, black, and/or Hispanic hires since new liberal arts grads are disproportionately female, black, and/or black compared to older, more experienced employees.

- expansion of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) programs and HR offices that will enforce (ii) and open up new, prestigious opportunities in training and enforcement.

- expansion of training and enforcement to cover alleged non-binary discrimination, as the older generation is mostly clueless or dismissive about any letters beyond LGB.

To be clear, I make no moral judgment here, nor do I mean to suggest that young adults are more self-interested than their predecessors. I draw attention to it only because youth are particularly hungry to frame their self-interest as morally pure causes, without realizing the many ways that virtue interweaves with vice. This helps explain the spiritual appeal in universities of many woke/DEI/multi-gender causes. The closest precedent is the way the prolonged draft of college-age students during the Vietnam War helped fuel ardently leftist anti-war sentiment, with traces visible in high Boomer participation at recent No Kings protests…

Read the entire article here.

Image by Monster Ztudio on Adobe Stock; Asset ID#: 203012034

It is interesting that the variance in ROI is not subject to a variance in the discount rate applied to the capital investment–tuition. That is, a university charges fixed-rate tuition, and fixed program design and duration, regardless of the degree expected return, or demonstrated rate of return. If ROI is an indication of risk, however, then all non-STEM programs are effectively venture risk categories (the limited high returns in them are strict outliers; moreover STEM is not high, but merely a risk-free rate in comparison): the expected return or pro forma payback for non-STEM, should be extraordinary. But there is a fascinating subtlety in the demonstrated financial returns: all the STEM programs require comprehensive secondary education preparation in order to participate successfully in them. That makes secondary school ROI criteria even more pronounced, and underscores why high school is at least as important as college. Moreover, outside applied music performance, all the non-stem categories are vulnerable to degradation in college standards, and functioning as effective remediation channels in the absence of secondary school qualification. This aggravates the return performance, and drives their ROI artificially low (this assumption does not account however, for residual value). University administration is generally indifferent to this efficiency and distortion problem, if it is subsidized by federal grant and tuition guarantee, underscoring their combined moral hazard in US higher education–and why the White House is right to challenge them. The national wealth by GDP rank implications are profound.

I was tempted to stop after the first abject sentence: ‘The primary function of universities is to educate skilled labor.’ But the headline ‘Most College Degrees Don’t Pay Off’ is belied by the very revealing first graphic.

And the accounting here on the “return on investment” is cuckoo. Take the seemingly hapless music major who gets a negative financial ROI. Unlike the econ major like the author. But the econ major may well work on dreck for all the money they get. Or try law! While the music major — I’ve known several well — has the opportunity to be suffused for a lifetime in sublime art. Yes, part of the “ROI” of college is the gift of learning, wisdom, beauty.

This is partly why “ROI” captures merely the market returns from wage compensation. In this case, a two-year A.S. degree from a community college in HVAC has a much higher ROI than a 4-year liberal arts degree, as the returns start immediately and currently face wage escalation from limited trained labor supply (interestingly). This is among the reasons that IRR (internal rate of return), versus ROI, is somewhat a better indicator of broad education economics, if one wishes to make such assessments, as it naturally captures the net present value, discount rate, and terminal value. This should be applied, however, especially to faculty research, and the Ph.D. Such research discount rates are enormous because most research fails, or never had actual return prospects. The MA/MS are more favorable, as they are not as susceptible to decreasing marginal returns, and are completed in 1/5 the time versus the Ph.D (US), and 1/3 (UK), with up to 100% equal research content, or higher. The problem of academic inflation (the JD is merely an LL.B; the Ph.D is merely a longer reading-period MA, and a faculty labor subsidy) greatly exacerbates the rate of return problem because time value, and longer fixed cost obligations (living expense) erode free cash flow. In plain language, the faster you get in and out of school, the better the economic return prospects (cf Jared Gould’s excellent essay, “Cut the Bloat, Graduate Faster”). As for both music, and the HVAC grad, it is interesting to note that the University of Chicago cites among its finest legal students a plumber; that music is ranked the best pre-law program; and among its most controversial, and brilliantly insightful faculty, is William Winslow Crosskey, an aluminum siding salesman. Outward-facing problem solving is arguably the one key missing ingredient, generally in the liberal arts curriculum, which is where ROI comes from. The curriculum of course can’t replace character.