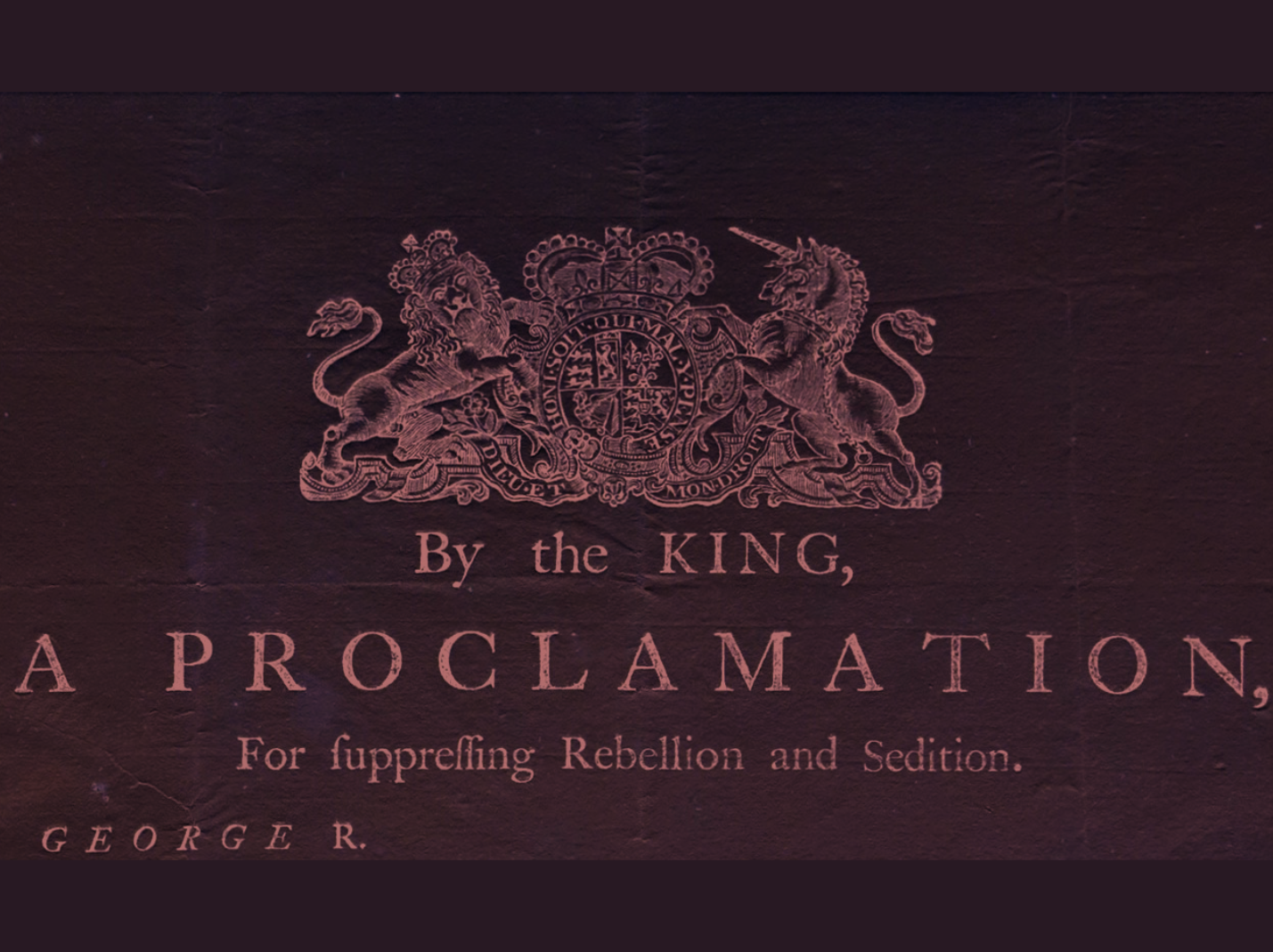

On August 23, 1775, King George III made it clear he was done with illusions about his American colonies. In his Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, he stated that “many of Our Subjects in divers Parts of Our Colonies and Plantations in North America, misled by dangerous and ill-designing Men … have at length proceeded to an open and avowed Rebellion.”

The King no longer saw the colonists as wayward children but as traitors, even forbidding all commerce with the American colonies. To underscore the gravity of his proclamation, George had it read aloud at Westminster, Temple Bar, and the Royal Exchange. Historian Rick Atkinson documents in The British Are Coming that the reception in London was not uniformly loyal. When it was read to Parliament, “hisses” were heard, a telling sign that not all were eager to see their country plunge into a transatlantic war. But standing in the way of the King was not likely to bode well. He ordered his subjects across the empire to act accordingly: “We do… strictly charge and command all Our Officers as well Civil as Military, and all other Our obedient and loyal Subjects, to use their utmost Endeavours to withstand and suppress such Rebellion” and expose all treason to bring “condign Punishment” to those responsible.

His words were blunt, and unlike the divided Congress in the colonies, he wasn’t mincing words. To Parliament and his subjects in Britain, supporting the American cause was treason. To the colonists, the message was also clear: they were rebels, and the Crown would crush their rebellion.

[RELATED: We’ve Reached the Summer of 1775]

Congress, meanwhile, was not and had not been so direct. On July 5, 1775, it approved the Olive Branch Petition, a nearly 1,400-word document signed by 48 delegates, including John Hancock, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams. As Peter Wood describes it, the petition was full of protocol and almost comic deference, calling the King “His most excellent Majesty” and “Most gracious sovereign.”—no one in Congress truly believed this flattery. The text praised Britain’s “mild and just government,” thanked the Crown for protection from “ancient and warlike enemies,” and expressed an “ardent desire” to restore harmony. But beneath the polite words was a warning: the King’s ministers had pushed things to the edge of bloodshed, and he needed to step in.

This was diplomacy as high-stakes performance—part plea, part veiled threat, part posturing for both the King and the colonists, balancing caution with resolve. The very next day, Congress revealed its hand. The Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms justified the resort to force, addressing not just the colonists but the world. Perhaps for outside observers, these documents expose Congress’s masterful doublespeak: pledging loyalty while sharpening swords, appealing for peace while preparing for war—leaders, then as now, shape their words to keep options open, save face, and protect themselves as events unfold. From the King’s perspective, his proclamation made perfect sense.

For the colonists, however, the refusal to even read the Olive Branch Petition—which reached London on September 1—closed the last door to peace. The two sides weren’t just talking past each other; they were already fighting, and George III made clear the colonies would face the full force of the Crown.

By late 1775, the lines were drawn, not just in ink but in gunfire. Reconciliation was impossible, and revolution was now inevitable.

Follow Jared Gould on X, and for more articles on the American Revolution, see our series here.

Art by Beck & Stone

The three things to remember here are first that while the population of Boston was 16,000, the king had sent 4,000 troops to Boston, which was a much geographically smaller city than today.

To put this into perspective, it would be like Trump sending 175,563 soldiers into DC, or 680,327 into Chicago — and to put those numbers into perspective, the entire US Army (worldwide) currently has about 445,475 active duty soldiers today.

One out of every five persons in Boston was a British soldier — but if you break the 16,000 down, it’s roughly 8,000 males, of whom about half (4,000) are in the age 15-30 cohort of young men looking for money to start/support a family. For every one of these young men, there is now a British soldier competing for the same jobs, and willing to work for less (which they were allowed to do) creating the same problem we have today with illegal aliens, only worse.

Yes, fraternization was the second issue.

And then this exacerbated the growing divide (becoming a civil war) in Massachusetts between those who benefited from the British and those who didn’t. In Massachusetts, the Revolution was a Civil War.

I think King George knew this, just didn’t realize that the third that remained neutral would remain neutral instead of supporting the Crown.

No, in Massachusetts at least, the Crown had taken sides in a civil war between Americans.