The world is changing quickly. In the 2010s, computer science was considered one of the most “marketable” majors. Nowadays, it has an increasingly high unemployment rate. Philosophy on the other hand, once the caricature of a “useless” major, is now being praised by people like Marco Argenti, the CIO of Goldman Sachs, who stated in April 2024 that future engineers should study philosophy as a supplement to traditional engineering coursework in order to be able to develop “a crisp mental model around a problem” and “debate a stubborn AI.”

Argenti’s commentary illustrates the fact that our economy is changing. The economic model of the last century rewarded specialization and the development of domain-specific skills, like coding. Yet with AI (artificial intelligence), the value of these advantages is diminishing. When mundane tasks are automated, critical thinking, general intelligence, intellectual dexterity, well-roundedness, and other soft skills, such as public speaking, become increasingly important.

[RELATED: Degrees Have Value—But Employers Shouldn’t Require Them]

Many college graduates have been misled by our higher education system and its emphasis on “majors,” which can cause them to pigeonhole the scope of their potential. Moreover, in my experience, many college students mistakenly view college as a form of trade school and assume that there are jobs directly connected with their majors. University web pages frequently provide information about what types of jobs are available for certain majors. While this information may be helpful in some instances, this framing can limit individuals’ occupational endeavors and lead to an underestimation of the possibilities available to them.

When I studied behavioral science, the science of human decision-making, at the London School of Economics, many of my classmates aspired to secure “behavioral science” jobs—whatever that meant—rather than applying their critical thinking and quantitative skills in actual jobs, such as finance. Students should walk away from university convinced that they can do almost anything, but in practice, it seems that the opposite is true.

There have been many prominent voices advocating that AI is going to cause severe disruption in the economy. The CEO of Anthropic, one of the largest AI startups, has predicted that in the next one to five years, AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white collar jobs and spike the unemployment rate to between 10 percent and 20 percent. While the long-term net effects of AI on the job market remain to be seen, it is indisputable that the technology will cause major disruption, especially in industries such as trucking and transportation.

In a chaotic and unpredictable world, the only thing that individuals can ultimately rely on, more than anything else, is their ability to improvise, adapt, and overcome. The tenacity of the human spirit enables individuals to always rise to the occasion and find ways to produce value. For example, suppose the demand for human capital becomes limited in traditional industries due to automation. In that case, this does not prevent people from pursuing alternative lifestyles and finding other ways to utilize their human capital.

Homesteading and small-scale agriculture, for example, could be a viable opportunity for many—especially when more than three hundred million acres of farmland is expected to change hands in the next twenty years. The government should take steps to ensure that people can fully realize their human capital through eliminating occupational licensing requirements, implementing a modernized version of the Homestead Act, and abolishing property taxes to minimize the financial liability associated with property ownership.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his famous essay, “Self Reliance,” illustrates his understanding of the virtue of self-reliance through his discussion of “a sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet.” He states that such individuals are worth one hundred of the “city dolls” who go to the finest universities and complain forthe rest of their lives after not being “installed in an office within one year afterwards in the cities or suburbs of Boston or New York.”

Emerson’s words still hold true today. We should aspire to be like the study of New Hampshire and Vermont lads that Emerson spoke of. For these individuals, they have “not one chance, but a hundred chances,” and no matter what happens, they will always land like a cat on its feet. Those who cling to the past and their “skills” may find themselves obsolete, but those who embrace change and cultivate flexible minds never will.

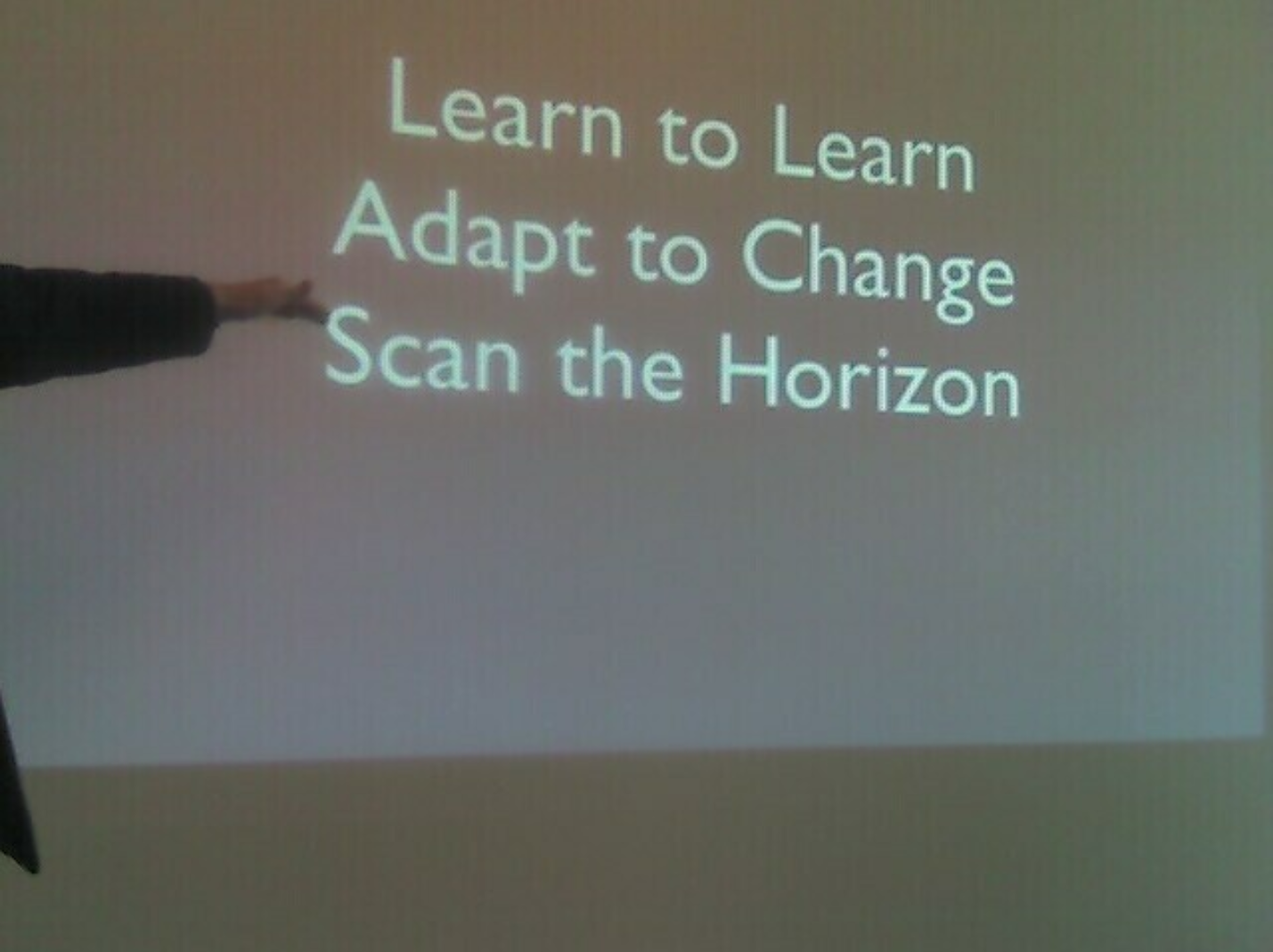

Image: “Learn, Adapt, Scan, Point” by Michael Porter on Flickr

“In the 2010s, computer science was considered one of the most “marketable” majors. Nowadays, it has an increasingly high unemployment rate.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gateway%2C_Inc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MCI_Inc.

I forget what the majors were 15 years earlier, but the same thing happened then — I will never forget the spring when seniors (who hadn’t even graduated yet) were being laid off from jobs they hadn’t even started yet.

It was a combination of two things — first the Dot Com boom and all kinds of companies that had never made any money — I almost went into that and saw the writing on the wall.

Then there was Y2K — back when memory was expensive, we only used the last two digits of years, and the clock was going to reset 1-1-00. So you had about 5-8 years worth of computer purchases accelerated in 1998 & 1999 — companies who would replace 10%-20% of their stuff each year instead replaced EVERYTHING so as to be Y2K compliant, and then didn’t need to buy anything for several years after that because all their stuff was brand new. This had also gotten rid of the rest of the 486 machines which were massive electric hogs when thinking — the absolute worst of ANY intel chip — and in offices with many computers, this was overheating offices (BADLY). So there had been an early market for Pentium machines starting 1995.

The AI bubble is going to crash soon too — no one wants to pay the electric bill…