Our society has become obsessed with science, engineering, math, and technology (STEM)—not only in the name of progress but also because we have deemed reading and writing almost wholly unimportant. According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the number of humanities bachelor’s degrees awarded to graduating seniors across American universities decreased by approximately 24 percent over ten years, dropping from 236,826 humanities degrees awarded in 2012 to 179,272 in 2022. On the other hand, STEM degrees are on the rise, with 30 percent of all awarded bachelor’s degrees now in STEM fields. While these trends might make sense in our late-capitalistic society—after all, no one wants to be stuck paying college tuition only to end up with a barista job—the general anxiety surrounding the humanities major points to a broader cultural shift: we no longer treat advanced literacy as essential to education or citizenship.

“Anti-reading” trends have become evident in aspects of our society—from the general decline of student reading comprehension to the virtual abolition of reading assignments—yes, reading assignments—in English classrooms. Students opt for efficiency over mastery, and with ChatGPT virtually eliminating the need for higher-order reading and writing skills—at least from the perspective of high school students looking to pass their English classes—a dwindling number of my current high school students can write a sentence on their own. Nearly all of my seniors, furthermore, have expressed a desire to study artificial intelligence (AI) in some capacity, and few, if any, are able to name a single complete book they have read throughout their high school careers. The irony, of course, is that as AI automates coding, data analysis, and other once-coveted skills, even STEM degrees are beginning to lose their luster. Nevertheless, students continue to prioritize logarithms over Shakespeare, believing that knowing how to read and analyze complex texts will do little for their future careers.

While it might be easy to blame their teachers or the rise of LLM use for this catastrophe, I believe that the decline of advanced literacy cuts even deeper: we have become so hyper-fixated on science, progress and technology that we have dressed up many benchmarks for STEM readiness under the guise of “reading comprehension,” convincing ourselves that our students can, indeed, read when, in reality, they are completing tasks that absolutely have nothing to do with reading or writing.

[RELATED: ‘Reading and Analyzing Are Not Essential,’ Says the College Board]

Nowhere is this societal confusion more evident than through the 2023 redesign of the SAT.

Since its debut in 1926, the SAT has assessed college readiness in students across America. In the words of the College Board, the test is designed to “demonstrate knowledge and skills in areas that current research tells us are most critical for college readiness and success.” What this tells us is that every new update of the SAT reflects the trends of the times—the 2016 SAT redesign, for instance, moved away from logical reasoning questions on the math section in favor of standard textbook math concepts taught in Algebra, Geometry, and Precalculus classes, suggesting a rise in the demand for students prepared to tackle higher-level math courses in college. But while the most recent SAT has kept its math section virtually unchanged from the previous iteration, the update to the reading and writing sections is appalling.

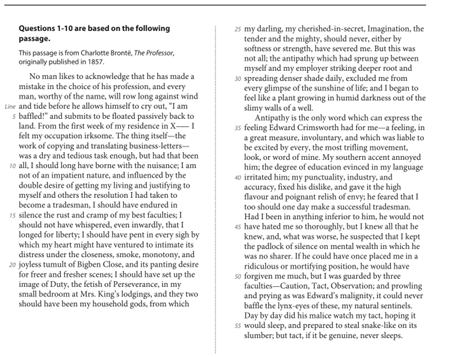

Gone are the days when students were expected to read multi-paragraph passages from great literary works, such as in the below excerpt from Charlotte Brontë’s The Professor, taken directly from a 2016 SAT reading section.

The new SAT questions look something like this:

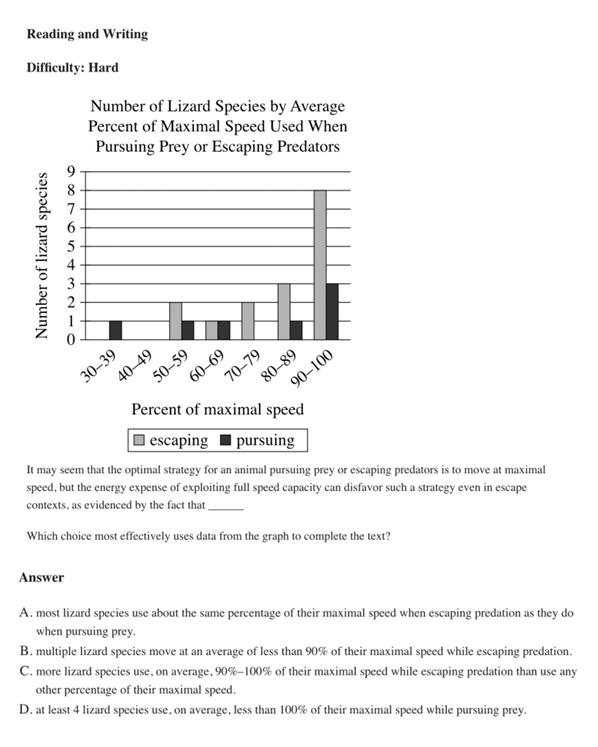

A question from the SAT reading section. Correct answer choice C.

My memory might be deceiving me—it’s been over 10 years since I graduated from high school—but I don’t recall ever being taught to read bar graphs in my English classes. I learned about scales and axes in both my science and my math classes, but I am not positive that data from lizard species ever surfaced in class discussions of Macbeth—though there might have been something about lizard legs in Act 4. What these SAT questions test is not reading comprehension at all but interpretation of data—skills essential to careers in medicine, research, finance, or tech, but almost entirely irrelevant to humanities fields. And while I agree that a well-rounded education is essential for students looking to go into any field—knowledge of bar graphs helps me track my book sales, for one–the question above belongs more on a math and science section of the SAT—certainly not on a section purporting to test reading comprehension!

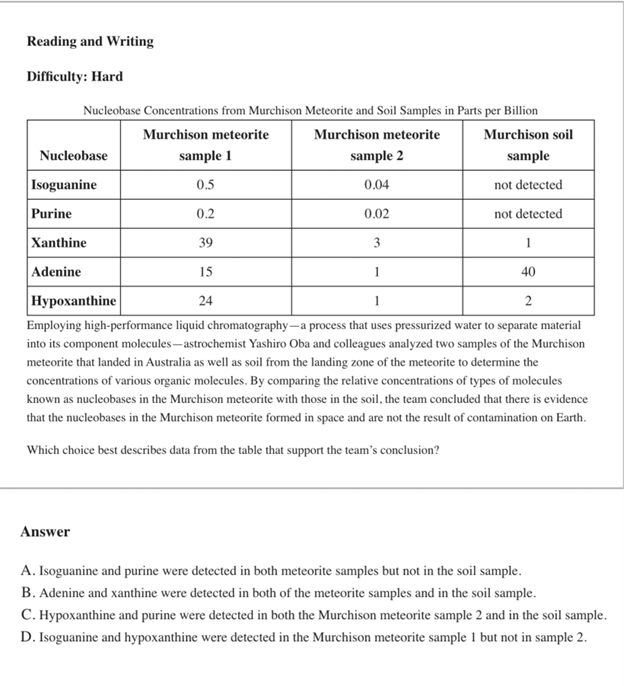

Let’s take another example:

A question from the SAT reading section. Correct answer choice A.

This particular question tests the interpretation of data pertaining to nucleobase concentrations in meteorite and soil samples. Again—I don’t know about you—but I certainly don’t remember learning about nucleobases in English or history classes. These sorts of questions seem to belong to a science section—such as the one on the SAT’s competitor test, the ACT. And as someone who scored perfectly on the reading and writing sections on the ACT but who genuinely struggled with the science section, I can tell you that interpreting data about nucleotides has nothing to do with aptitude for words.

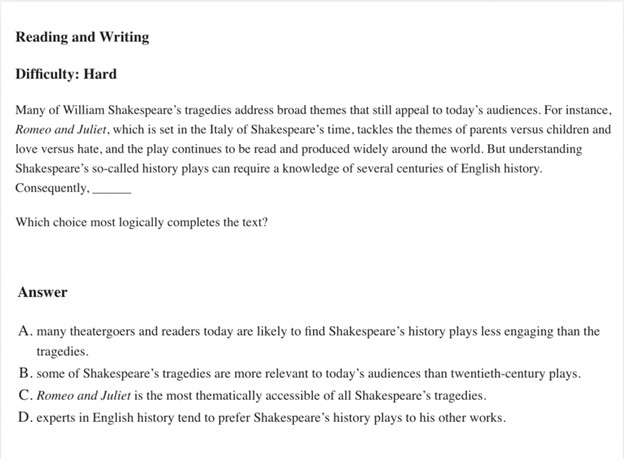

And while there are still a few genuine reading comprehension questions on the new SAT, they never run longer than a paragraph and don’t require substantial attention to detail. The following question about Shakespeare—which runs just three sentences long and which I believe any student can answer in their sleep—tests nothing about knowledge of Shakespeare in the way the previous question requires a basic understanding of science experiments. In fact, the question, which is marked with the “Hard” difficulty, seems to ridicule the very notion that advanced reading comprehension is necessary at all. Compare this question with the passage from Charlotte Brontë, and you’ll see what I mean.

A question from the SAT reading section. Correct answer choice A.

[RELATED: The Mythicization of Educational Testing]

What happens as a result is that students interested in STEM gain a large advantage because of the questions on the SAT are now STEM questions, and students interested in the humanities have to learn STEM concepts in two different capacities. Simply put, anyone can pass the reading comprehension test, and students who are strong in humanities not only don’t get to demonstrate their skills but are also told that the very skills they excel at no longer matter. STEM students, on the other hand, are persuaded that they can tackle reading comprehension when, in reality, we have collectively decided that reading comprehension is no longer important.

But reading comprehension is essential for higher-order thinking. It is the very vehicle through which we express our ideas, solve problems creatively, and risk being fully human. Lizards and nucleotides are great, but they cannot exist in isolation—they cannot exist without a great thinker to make sense of them and to tell us why they matter. In abandoning literacy, we risk producing a generation of technicians who can analyze everything but understand nothing—putting a wrench in the very idea of “progress.”

Follow Liza Libes on X.

Image by smolaw11 on Adobe Stock; Asset ID#: 279431362

I am in violent agreement with Ms Libes’ contention that students need to be able to read and write. However, the article wasn’t very convincing – there’s no hard evidence that “STEM” is to blame.

The SAT is a mess – ’nuff said.

Lowering standards for boys in reading makes as little sense as lowering standards for women in the military. But we do have a “male” problem in education. The 2:1 female to male disparity in higher education (less for Caucasians and esp. Asians, but more for Blacks) is of great concern. But it starts in K-12: giving boys uppers because they act like … boys; disparaging men who should be role models; thinking that boys and girls are alike therefore they should learn the same ways.

Ms Libes’ article ignores a few other important factors:

• The Humanities, in too many IHEs, have been captured by indoctrinators, not scholars.

• The classics, the basis of our culture, are MIA – abandoned – in their classrooms. And what’s left is boring, and not useful except for getting a passing grade.

• Almost all disciplines in academia have been impacted by racially-conscious hiring practices. In too many places, merit is secondary to the “correctness” of one’s credentials.

• And, to me, the most criminal of these, the indoctrinators seemingly have abandoned the goal of a liberal education – the ability to think.

“we no longer treat advanced literacy as essential to education or citizenship.”

This is true. It’s happened for a lot of reasons. Perhaps the biggest reason is that the humanities have made themselves into objects of ridicule. In many ways.

It’s actually happening with the sciences now. Which are becoming objects of derision among some extremists of the right. I think — I devoutly hope — that it will boomerang against the right — before they cede scientific leadership to other countries.

But some of it has been brought upon the sciences by some branches of science themselves. The insistence that the idea that a person can change his sex is a scientific truth is a big example. It may be discussable, but to put it mildly, it is hardly a scientific truth, such as the statement that water is formed by the reaction of something called oxygen with something called hydrogen.

It’s not the right that is spending lots of money we don’t have to study the sex lives of lesbian wambats in the Amazon Basin. I made that up, but there are way too many actually funded studies along these lines. And then the inability to replicate is a scandal of its own…

It wasn’t Conservative luddites who did this — it was the scientists themselves, and their scientist peers who didn’t say anything. IF we lose predominance in science, it will be because American scientists didn’t police themselves.

Conservative Luddites love to mock wacko-sounding studies in the jungle, usually without showing any curiosity about the scientific rationale of a given study. But if you dig, you’ll find out that a lot of interesting and important things have been uncovered by these studies.

No, when we cede scientific superiority, it will not be becasue of American scientists. It will be because, among other reasons, Conservative Luddites.

Perhaps if the purported “researchers” were specific as to the scientific rationale of their purported “research”, the Luddites might be willing to fund it.

And perhaps if scientists would police their own, it wouldn’t be so easy to parody research.

And as to “academic freedom”, if faculty had policed that, they wouldn’t be looking at some of the things that are coming, such as AI-based monitoring of their lectures, but I digress…

Enjoy your laugh, Mr Ed, Chinese science will crush American soon enough, and your MAGA pals and their CCP pals will be happy.

I do look forward to the Nobel prizes. Maybe the era of waning American triumph.

My take on this is quite different, and far more cynical.

1: For every Black male in college, there are at least two Black males, and the same ratio is rapidly approaching amongst White students.

2: While it’s rarely mentioned, the “boy gap” in reading & writing is far greater than the “girl gap” in STEM — and while the “girl gap” has been closing over the past 30 years, the “boy gap” remains unchanged. This is all reflected in the NAEP.

3: Young ladies have long gone to college because “it’s where the boys are.”

4: The demographic bottom falls out in Fall 2026 — recruitment for which has already started….

QED — I think that this is an attempt to re-norm the SAT along gender lines.

The feminists would scream bloody murder if they admitted that they were trying to raise the scores of boys versus those of girls, but if they do this, how many people even know about the “boy gap” in the first place???

Yes, Ed is cynical — I survived Planet UMess….

For every Black male in college, there are at least two Black females….

Grrrr…..