One week ago marked the anniversary of October 7, 2023, when Hamas terrorists murdered 1,200 Israelis and took 250 more hostage. While the hostages have since been released and initial steps toward a ceasefire are underway, tensions on college campuses, and the fear surrounding them, show no sign of easing alongside shifting geopolitics.

Columbia University, for example, last week allowed the installation of chairs representing each person murdered by Hamas in the worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, as reported by Chance Layton, Communications Director of the National Association of Scholars. The display was meaningful, but it was undercut by other measures that reveal how tense the campus remains.

In what seems to have been a preemptive move against vandalism, violence, and other disruptions by anti-Zionist activists over the past two years, Columbia restricted campus access to students, faculty, and staff only. Even alumni, who often wield outsized influence, particularly alumni donors, were barred for nearly two days. This restriction blocked my own research fellow, a Columbia alumnus, from canvassing for the NAS’s forthcoming study on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” and anti-Semitism. The ban, therefore, felt not just heavy-handed, but misguided.

While outside groups such as Within Our Lifetime, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), and American Muslims for Palestine (AMP) have caused disruptions at Columbia and other campuses, the university itself fosters the conditions for unrest from within. For example, the Center for Palestine Studies hosts some of the most prominent and polarizing voices in the Israel-Palestine debate, including Rashid Khalidi, heir apparent to Edward Said. Both have promoted the settler-colonial narrative, a framework that denigrates Zionism and miscasts Israeli Jews as white oppressors.

Other professors include Joseph Massad, a prominent figure in the film Columbia Unbecoming, which focused on the ways that Columbia professors had discriminated against Jewish students in their Palestinian pedagogy. Massad supposedly once exploded at a Jewish student whom he felt had insufficiently acknowledged Palestinian suffering. Another professor, Katherine Franke, who is still featured on the Center for Palestine Studies website, was removed from her tenured position following multiple allegations of pro-Palestinian bias in her classroom.

The Columbia ban may have prevented some students from joining the massive protest that swept through the city at the behest of activist group Within Our Lifetime. But just because the Columbia student body didn’t join this protest with the same force as the NYU students does not mean there isn’t significant support for Palestine among Columbia students. The student government overwhelmingly voted for divestment in 2024, and the University Judicial Board punished over 70 students with revocations, expulsions, and suspensions earlier this summer.

Admittedly, as Layton wrote, compared to the two previous years, the climate at Columbia was subdued. This may have been the result of the ban or the continued lashing Columbia has received from the Trump administration, especially since its encampment.

Still, the reason why the ban felt spurious is that the anti-Zionist philosophy originates within the university. It is supported by professors and students, some of whom have been punished and removed, but many of whom have not. The movement gains strength from the outside, but its roots proliferate within the academy.

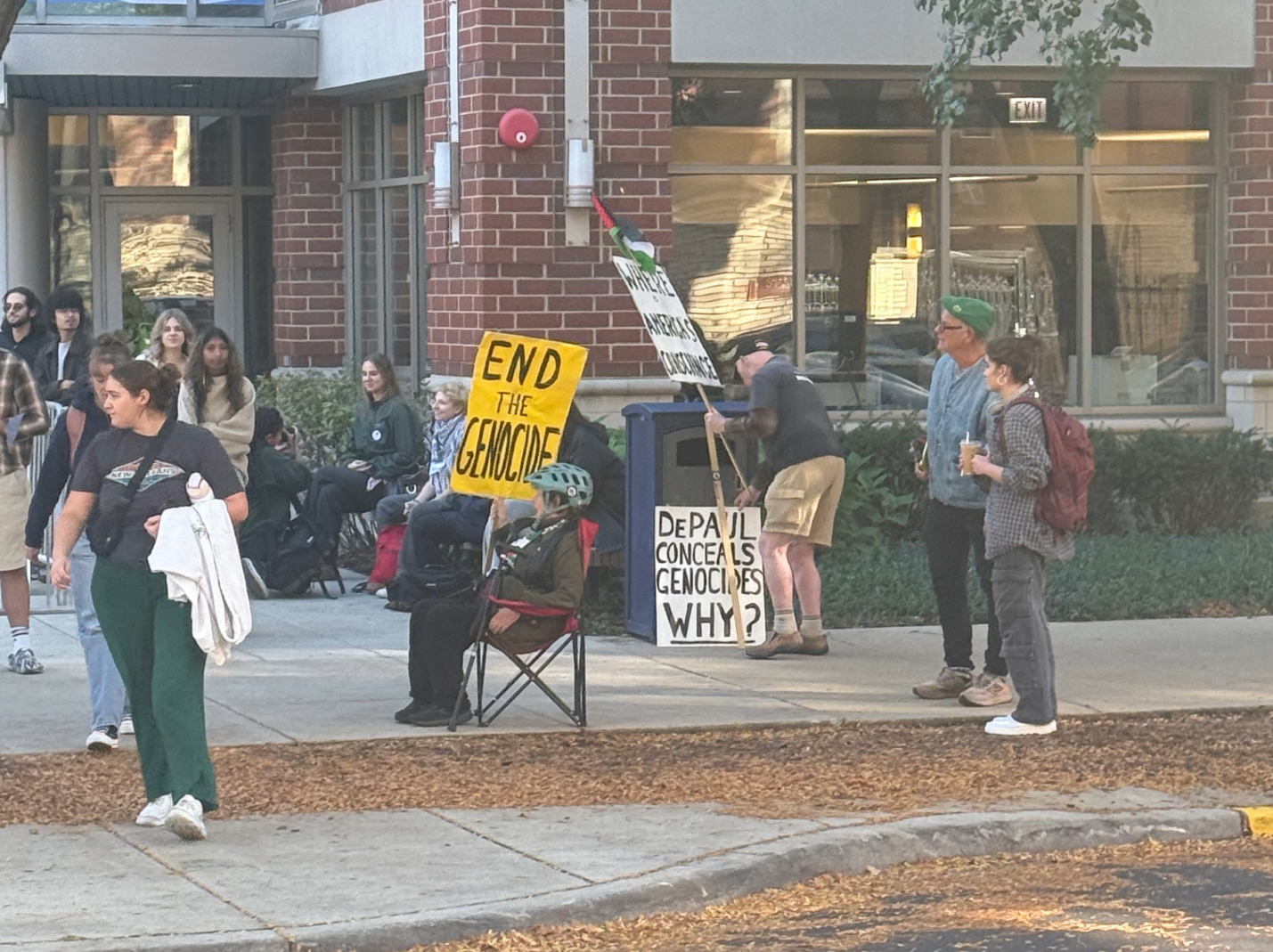

An incident from another school perhaps illustrates this inside-outside relationship further. At DePaul University, many pro-Palestine groups, such as Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), have been banned from campus. Yet, Within Our Lifetime, found a loophole and exploited it to organize a student protest. They protested on the sidewalk outside the student center (see the images below). This area, although technically not part of the campus, is so indistinguishable from the campus that students were often confused about its boundaries, wondering if they could still visit the student center. The protest, which immediately followed a union protest at which many of the same students were present, involved several bullhorns and was loud enough that it could easily be heard in the adjacent campus area in front of the student center and to all the students entering and exiting that building.

Images by Benjamin Dorfman, taken at DePaul University during its October 7, 2025, pro-Palestine protest

[RELATED: Mamdani’s Anti-IHRA Stance Will Put Jewish Students at Risk]

In a way, the DePaul protest embodied the nebulous relationship the anti-Zionist movement establishes with boundaries at the university. Anti-Zionist professors promote pro-Palestine, and by extension pro-Hamas, ideology from within, gaining support from students and protection from the administration. At the same time, foreign influence penetrates from the outside, amplifying the message through social media and sympathetic news outlets. Because the university traditionally wields so much influence—anti-Semitic incidents increase in states where local campuses experience high levels of such activity—it has long had porous boundaries, and with regard to anti-Zionism, no one is quite sure where those boundaries begin or end.

It should be remembered, nevertheless, that October 7 occurred because of porous boundaries. The university needs to lead and set a clear boundary, not just on days that it fears destruction. It needs to recognize how the anti-Zionist ideology promoted by its own professors contributes to this destruction, and take steps to hold those professors accountable for creating an environment in which Jewish students are put at risk. When that happens, university bans may actually have meaning.

Cover by Michael Kaminsky, taken at DePaul University during its October 7, 2025, pro-Palestine protest

This is a critical and deeply troubling issue. Many of the analyses point to a failure of university leadership and specific ideological frameworks within certain departments.

My question is about the mechanism of change. Given that many of these problems are rooted in tenured faculty and entrenched administrative ideologies, what are the most effective levers for reform? Is the primary path through external pressure (donors, legislators, accreditation bodies) or is there a viable strategy for fostering change from within, by empowering dissenting faculty and students to shift the institutional culture?

exploiting a loophole is not nefarious, but when i look at these photos what i see is that an adult male unaffiliated with the campus walked around and took creepshots of teenagers.

You think those geriatrics look like teenagers!? As for the vanishingly few protesting students in these photos, I’m sure they’re proud to be documented rallying on behalf of barbaric terrorists. That’s why their faces are covered, right?

As much as it pains me to say this, schmucks have civil rights, too. The issue with what happened at Columbia (et al) last year was not the schmucks saying “look at me, I’m a schmuck” but their violation of the rights of others.

it would be incredibly poor taste on their part, but I’d defend their right to *quietly* wear shirts with Hitler’s face on them — let them tell the world who they really are. Truth is stronger than falsehood — they aren’t going to win an argument on the merits.

Hence the issue of the sidewalk outside DePaul University — if the sidewalk is owned by the City of Chicago, then absolutely anyone (including schmucks) has the right to use it. And as the US Supreme Court ruled a half century ago, the City of Chicago doesn’t get to regulate the content of speech.

“This area, although technically not part of the campus, is so indistinguishable from the campus that students were often confused about its boundaries, wondering if they could still visit the student center.”

This is what happens when you use public sidewalks as part of your campus — when you chose to have an urban campus. They could instead buy a few hundred acres of land upstate, put a fence around it, and not have to deal with things like this. Except they also wouldn’t have the benefits of an urban campus and city life.

If access to a building is blocked, that’s what police are for. It could get complicated quickly, maybe even suing the city, but if people block access to your buildings, there are things you can do.

“The protest, which immediately followed a union protest at which many of the same students were present, involved several bullhorns and was loud enough that it could easily be heard in the adjacent campus area in front of the student center and to all the students entering and exiting that building.”

What do city regs say about noise? Noise, not content — dB levels….

Now as to students hearing what the schmucks are saying — what are they, blushing virgins?!? Are they so insecure that they will implode if they learn that there are nasty people in the world?!? These are adults — aren’t they?!?

This is right back to Words that wound and hate speech codes, something I’ve been fighting for 40 years. And back then, it was the anti-Semites who championed censorship…..

I would also encourage people to read Suzannah Alexander’s recent article here.

SEL and the conformity that it produces is a far greater threat than loud-mouthed anti-Semites, regardless of how offensive they are. The Holocaust happened because of a culture of conformity, the lack of people to say “bleep you.”

People forget that the Holocaust started with the disabled, and it could have been stopped at that point — it almost was.