On both sides of the Atlantic, complaints are frequently raised about the relative absence of intellectual and political diversity in the Academy. The main emphasis of these criticisms is that teachers holding conservative and right-wing views are seriously underrepresented in university departments, particularly in the social sciences and the humanities. Responsibility for the feeble state of political diversity is often attributed to unconscious and sometimes conscious discrimination.

Related: Pollyannas on the Right–Conservatives OK on Campus

Earlier this year, a report by Ben Southwood, published by the Adam Smith Institute titled Lackademia: Why Do Academics Lean Left? argued that teachers with left-wing and liberal attitudes were overrepresented in relation to the views held by the population at large. The report stated that in the UK, while around 50 percent of the public supports parties of the right only 12 percent of academics endorse conservative views. Moreover, Lackademia claimed that it is likely that the overrepresentation of liberal views in universities has grown since the 1960s. It suggests that the proportion of academics who identify as Conservatives may have declined by as much as 25 percent since 1964.

The claim that conservative academics are an embattled minority is even more frequently asserted in the United States. For example, a study published last year ‘Faculty Voter Registration in Economics, History, Journalism, Law, and Psychology’ found that liberal professors outnumbered conservatives by a ratio of 12 to 1. Recently one conservative professor from the University of South Florida wrote that he doubts that he would have been hired ‘if my conservative views were known.’ A recent study of 153 conservative professors indicated that about a third of them adopted the strategy of concealing their political ideals prior to gaining tenure.

Related: Times Says Conservatives Unwelcome in Academia

Some American politicians have taken up this issue and demand that universities adopt a more ideologically diverse hiring policy. Iowa State Senator Mark Chelgren has filed a bill designed to equalize political representation on the faculties of state universities. The Bill aims to introduce a freeze on hiring academics until the number of registered Republicans ‘comes within 10 percent of the number of registered Democrats. It is likely that supporters of the Trump Administration will use this issue in order to change the political culture that prevails on American campuses.

During the past seven decades, concern with the ideological imbalance between left and right on campuses has been a recurrent theme in the conservative critique of higher education in the United States. Throughout the Cold War the domination of higher education by “liberal professors” was a concern that was constantly raised by conservative critics of the Academy. As two conservative professors, Jon A. Shields and Joshua M. Dunn recently noted the crusade against the allegedly liberal-dominated university was launched in 1951 with the publication of William F. Buckley’s book, God and Man at Yale. Buckley claimed that the university had become a haven for anti-Christian, atheist and liberal professors.

Alarmist accounts of the threat posed by college radicals dominated the headlines in the 1960s and 1970s. In recent times, protests against allowing conservative speakers on campuses – Charles Murray, Condoleezza Rice, Suzanne Venker, John Derbyshire – has re-raised interest in the precarious status of conservatives within academic culture.

On the Defensive

There is little doubt that in many academic disciplines conservatives face difficulty in gaining employment. The leftist historian Robin Marie has criticized liberal academics who refuse to acknowledge that they have a double standard towards the practice of academic freedom. Drawing attention to the double standard that prevails in higher education regarding the employment of conservative academics – a double standard which she approves- Marie wrote;

“Academic institutions, moreover, are spaces that are morally policed – it is not a coincidence, nor due solely to the weak evidential basis of their positions, that only a minority of professors in the liberal arts are conservative. Declining to hire someone, publish their paper, or chat them up at a conference are exercises in exclusion and shame which those in academia, nearly as much as any other community, participate in.”

Marie’s allusion to the practice of marginalizing conservative academics in the social sciences and the arts serves her purpose of reinforcing her claim that academic freedom is a liberal shibboleth. Most of her colleagues would be reluctant to go on record and acknowledge their anti-conservative bias.

However, it would be wrong to attribute the marginal position of conservative academics in the humanities and social sciences simply to self-conscious acts of discrimination. Since the end of the Second World War, conservative ideas have become marginalized within the key cultural and intellectual institutions of western society. In a frequently cited statement, the American literary critic Lionel Trilling declared in his 1949 Preface to his collection of essays that right-wing ideas no longer possessed cultural significance:

“In the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition. For it is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation. This does not mean, of course, that there is no impulse to conservatism or to reaction. Such impulses are certainly very strong, perhaps even stronger than most of us know. But the conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not, with some isolated and some ecclesiastical exceptions, express themselves in ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.”

Though Trilling’s boast about the dominant status of liberalism contained an element of exaggeration there is little doubt it corresponded to developments in the 1940s.

It was the experience of the inter-war years and of Second World War that served to discredit the influence of right-wing and conservative intellectual tradition in Western Culture. The 1930s depression, followed by the rise of fascism significantly diminished the appeal of right-wing ideas. It also solidified the association of intellectuals with left-wing philosophies. From this point onward, conservative thought became increasingly marginalized within the humanities and the social sciences. Which is why today it is difficult to recollect that until the second half of the last century right-wing thinkers constituted a significant section of the western intelligentsia.

Its Cold War rhetoric aside, McCarthyism can be interpreted as a belated attempt to discredit the moral authority of the liberal intellectual by equating its nonconformist ethos with disloyalty. However, despite the significant political influence enjoyed by McCarthy within American society, he could not defeat the liberal political culture that prevailed in higher education.

In her essay on ‘The New Class’(1979), the Conservative thinker Jeanne Kirkpatrick observed that the inability of McCarthy to make serious headway against liberal intellectuals meant that this group was able to strengthen its authority over cultural life in America. Kirkpatrick concluded that McCarthy’s demise and the growing authority of his intellectual critics was a “precondition of the rise of the counterculture in the 1960s.” Since the 1960s conservatives within the Academy have been more or less constantly on the defensive. One often unremarked symptom of this trend has been the growing trend towards the pathologization of the conservative mind.

The Presumption of Intellectual Inferiority

The marginalization of the conservative academic has been paralleled by the pathologization of the conservative mindset. Claims that conservatives are intellectually inferior to their opponents originated in the 19th century when the British Tories were frequently derided as the “stupid party.” Arguments about the supposed intellectual inferiority of conservatives claimed that those who remained wedded to outdated traditions lacked imagination and an openness to new experience. Since the defense of the status-quo did not require mental agility or flexibility, it was suggested that conservatives were likely to be left behind in the intellectual stakes. Only those who were prepared to criticise and question the existing state of society could be expected to develop a capacity for abstract and sophisticated thought.

From the 1940s onwards the insult of being labeled as stupid was often justified on intellectual and scientific grounds. Intelligence became a cultural weapon used to invalidate the moral status of conservative minded people. Inevitably this was a weapon that was most effectively used by those claiming the status of an intellectual. As Mark Proudman stated:

“The imputation of intelligence and of its associated characteristics of enlightenment, broad-mindedness, knowledge and sophistication to some ideologies and not to others is itself, therefore, a powerful tool of ideological advocacy.”

Ridicule as Moral Superiority

Making fun of the “outdated” views of conservative people and exposing their traditional ways to ridicule was one way of assuming the status of moral superiority. In this way, those with a monopoly over the possession of intellectual capital can present themselves as possessors of moral authority.

Often assertions about the intellectual inferiority of conservatives ran in parallel with claims about their psychological deficits. In the 1950s, Theodor Adorno’s classic Authoritarian Personality served to validate the dogma that the internalization of prejudice and the disposition for intolerance is a psychological issue. From this point onwards the conservative mind was increasing portrayed as authoritarian, inflexible, prejudiced and disposed towards simplistic solutions to the problems facing society.

Usually, the weaponization of intelligence to discredit groups of people tends to be challenged by the academic community. For example, Charles Murray’s, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life(1994) has provoked outrage on campuses. Riots broke out at Middlebury College earlier this year, leading to the cancellation of a speech by Murray. But though Murray has been criticised for linking people’s IQ to their predicament, such concerns are rarely raised when conservatives are the target of the weaponization of intelligence.

The representation of conservatives as less intelligent than their left-wing foes is frequently communicated by ‘research’ on the so-called conservative syndrome. The hypothesis of this syndrome is that conservatism and low cognitive ability are directly correlated. Such claims are frequently promoted by studies such as “Bright Minds and Dark Attitudes–Lower Cognitive Ability Predicts Greater Prejudice Through Right-Wing Ideology and Low Intergroup Contact.” The authors of the study claim that low intelligence in childhood serves as a marker for racism in adulthood. Moreover, poor abstract-reasoning skills are closely correlated with anti-gay prejudice. From studies such as this, it is tempting to draw the conclusion that simple children with low cognitive abilities grow up to be prejudiced conservatives.

The pathologization of the conservative mind inevitably influences attitudes and practices in universities. This sensibility not only calls into question the ideas that conservatives uphold but their moral and intellectual status. Instead of offering an intellectual critique of conservative ideology it simply devalues the integrity and intellectual capacity of the person holding such views. Consequently, many conservative academics experience the critique of their views as not part of an intellectual exchange of views but as a mean-spirited insult.

Not surprisingly many conservatives have become defensive when confronted with the put-downs of their intellectual superiors. In many societies – particularly the United States – some have become wary of intellectuals and hostile to the ethos of university life. Anti-intellectual prejudice often constitutes a defensive reaction to the pathologization of conservatism. In the United States, the unrestrained anti-intellectual culture of sections of the right, which sometimes appears as the affirmation of ignorance serves to reinforce the smug prejudice of their opponents.

There is little doubt that some of the complaints made by conservative academics about the unwillingness of sections of the academic community to tolerate their views are not without foundation. However, it is important to note that many would-be conservative intellectuals were accomplices in the marginalization of their views on campuses. Certainly from the 1960s onwards they did little to stand their ground in the social sciences and the humanities. Many of them opted to join conservative thinks tanks and became critics of the Ivory Tower from the outside. There is also something opportunistic about the way in some conservatives have embraced the status of being victims of the campus culture wars. Shield and Dunn get the balance right when they write

“As two conservative professors, we agree that right-wing faculty members and ideas are not always treated fairly on college campuses. But we also know that right-wing hand-wringing about higher education is overblown.”

They point out that after interviewing 153 “conservative professors in the social sciences and humanities, we believe that conservatives survive and even thrive in one of America’s most progressive professions.”

Of course, conservative academics should not have to adopt a survival strategy any more than left-wing ones. The maintenance of intellectual diversity is one that all sides of the academic community have in interest in upholding. Openness to a diversity of views and genuine academic freedom is the foundation of a liberal academy. As Steven Holmes observed in his important study, The Anatomy of Antiliberalism, “Public disagreement is a creative force may have been the most novel and radical principle of liberal politics.”

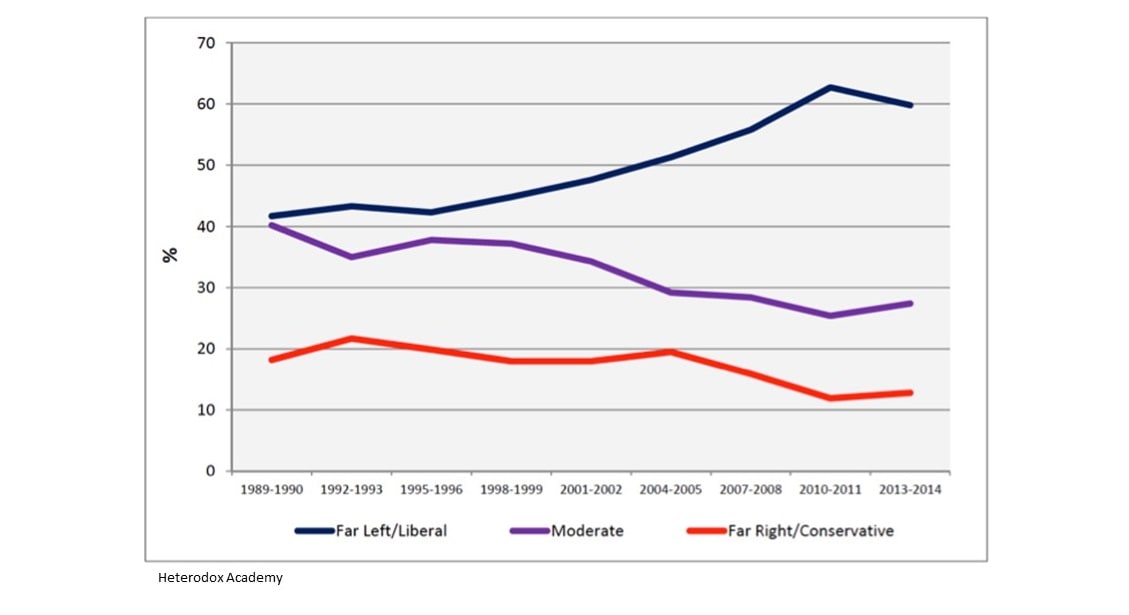

Chart: Courtesy of Heterodox Academy.

I am a 54 year old sophomore , returning to College after 25 years. I am also a grandfather raising 2 adopted grandchildren, with the help of my wife. School is secondary. It’s a good thing because the Professor babying grown adults so they can get passing grade is sickening. When I talk with. Professor’s about their excuse is this is a different time, students learn differently. While this may be true the answer is not walking around a classroom during a test and coaching them to the right answer is not helping them or their students. When I am stopped on the way out the door, and encouraged to change an answer because she could I got it wrong, is something I just can’t stomach. Complaints have been ignored and then and accusations of doing things I haven’t done. I done with his class and maybe done with school. The sad part is that I can’t run from it because in a few years they could be my boss. And this doesn’t even bring politics into it.