Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the soon-to-be-published National Association of Scholars report, Rescuing Science. It has been edited to align with Minding the Campus’s style guidelines and is cross-posted here with permission.

Public funding of academic research is shaping up as a major political confrontation between universities and the Trump administration. The first shot fired in February was the administration’s attempt to rein in excessive overhead costs. Since then, the conflict has escalated into the Trump administration using research grants as leverage in the administration’s civil rights agenda. The campaign began with a threat to withhold $400 million in federal grants to Columbia University for deficiencies in protecting the civil rights of Jewish students in the face of strident and disruptive actions by Hamas sympathizers. Since then, the front has expanded to a number of private and public universities, most prominently Cornell—$1 billion under threat of withdrawal—and Harvard—$2 billion of federal grants at stake.

At the heart of this ballooning controversy is a sobering fact: government is now the majority funder of academic research in the United States. There is a rarely mentioned irony at the heart of this. Research funding always comes with expectations and strings attached. It has always been so. Since 1950, when the federal government became the majority funder of academic research, it should come as no surprise that an explicitly political body, the government, makes political demands on how its funds are spent. Whining when your major funder’s political priorities change is hollow and juvenile.

Nor is it the major concern facing academic science. Federal funding of academic research has established a host of perverse incentives that have degraded scientists’ ability to conduct the very thing academic science is intended to do: foster curiosity-driven research. Among the undesirable outcomes these perverse incentives have produced have been:

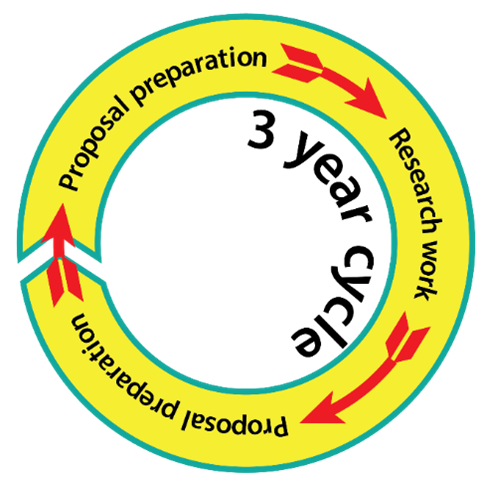

- It is wasteful of scientists’ time and talent. It has numerous built-in inefficiencies that divert their time and effort away from discovery and toward an endless chase for grant revenues, to the detriment of discovery (Figure 1).

- Funding decisions are arbitrary and capricious.

Figure 1. The research project “grants treadmill. If a scientist is lucky, he might be able to devote a third of his time to actual research, with the rest consumed by proposal preparation and administration.

- It favors established scientists and stifles creativity and novelty among younger researchers.

- Universities are incentivized to view research as an exploitable revenue stream rather than a means of fostering discovery.

- It has encouraged a counterproductive ethic of production among scientists, which has crowded out the ethic of discovery that prevailed prior to World War II.

- Making grant funding conditional on compliance with political agendas has become a backdoor portal to politicizing basic science.

In 1950, the federalization of academic science began with a hopeful goal: to foster fundamental research in universities. Now, seventy-five years later, that hopeful experiment has failed. It’s past time for a radical rethink of what we expect of academic science, how it can be fostered, and whether there should be government funding of academic science at all.

[RELATED: Indirect Costs Make Science a Revenue Game Not a Discovery Quest]

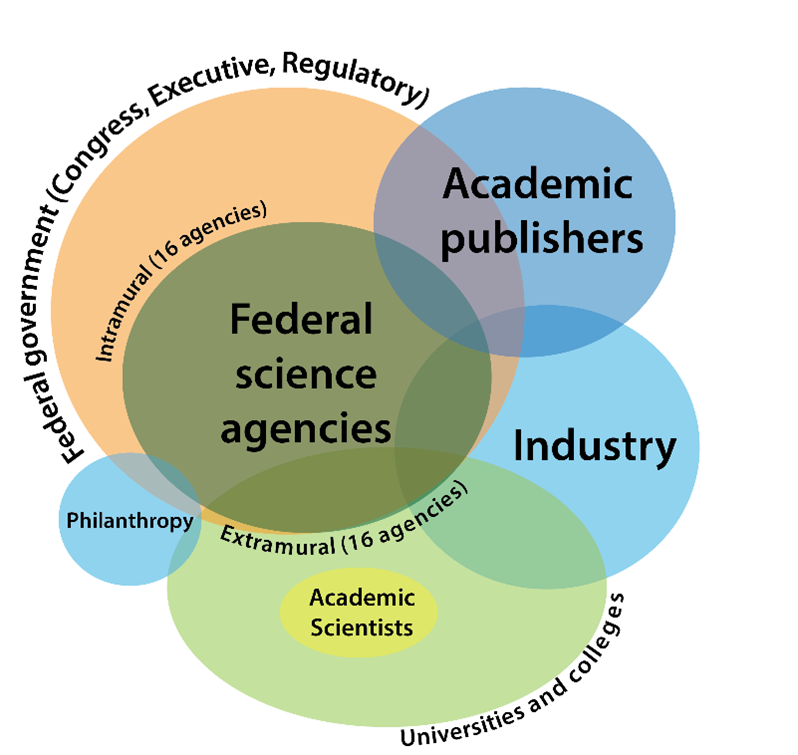

The problem plaguing the academic sciences is not funding per se but how generous federal subsidies—$109 billion in 2023—have subordinated scientific discovery to the more powerful interests of administrations, funding agencies, and assorted rent-seekers that feed off that subsidy (Figure 2). Scientists now find themselves thoroughly enmeshed in a funding system that turns them into turnkeys for spigots of government research funds. To rescue the academic sciences from this parlous state, scientists must somehow be extricated from the tangled web of collusion that currently ensnares them.

Figure 2. The modern academic science ecosystem. Scientists’ role is no longer to discover but to generate revenues that support a variety of contrary interests among university administrations, government, and various rent-seekers.

The entanglement began in 1950 with a political compromise to establish the National Science Foundation (NSF). In 1945, President Roosevelt tasked his science advisor, Vannevar Bush, to make the case for federalizing the academic sciences. Bush’s report, Science: The Endless Frontier, was his plan. Among its recommendations was establishing a National Research Foundation that would fund science through open-ended block grants to universities, using the funds as universities had done with institutional funds: monies available to scientists that universities and university research committees could control. This was considered well-suited to the ad hoc, fluid, opportunistic, and inspiration-driven nature of basic research.

President Truman vetoed the first attempt to establish the NSF in 1948 for lacking the accountability that normally goes with federal funding. To meet Truman’s concerns, the proposal for open-ended block grants was dropped, and Truman signed into law the 1950 National Science Foundation Act. In deciding how to distribute its funds, the NSF adopted a research contract model of short-term—three years, typically—project-oriented research grants.

Most of the pathologies outlined above afflicting modern academic science are traceable to this decision. As an aside, most of these pathologies were predicted in Science: The Endless Frontier. Returning the academic sciences to what they should be—havens of basic research—and what federal funding was supposed to support will mean, at the least, reversing the funding model that was put in place in the early 1950s.

One place to start will remove backdoor instruments of politicization that are presently baked into the system of grant funding, Broader Impacts (BI) statements being the most blatant and abused. When evaluating grant applications, reviewers are asked to consider two Merit Review criteria. Broader Impacts is one; the other is Intellectual Merit (IM, sometimes called Scientific Merit). Until 1997, Intellectual Merit was the sole merit review criterion. Introducing the Broader Impacts statements opened the door for the politicization of academic science by conditioning funding decisions on ideological conformity to some political agenda, most prominently conformity to DEI ideology. If a Broader Impacts statement is deemed lukewarm in its commitment, funding is jeopardized. Your commitment to “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) is lukewarm? Kiss your funding goodbye.

Reforming Broader Impacts statements, which have been undertaken several times since 1997, is not an option. If left in place, they open the door to continued politicization of basic science. Where it conformed to DEI ideology in the past, it is now going to conform to civil rights law or some other political issue. To restore intellectual independence to academic researchers, the Broader Impacts statement should be eliminated altogether, and the Merit Review criterion should be returned solely to Intellectual Merit.

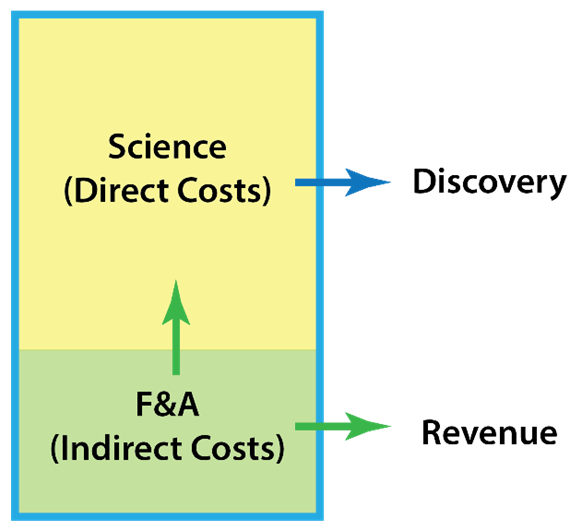

A deeper entanglement is the current practice of bundling overhead costs in with a proposal’s direct costs, that is, the funds that support the scientific work—bundling the two pits the competing interests of scientists and administrations against one another. While scientists pursue research funding for discovery, institutions want research grants to generate revenue (Figure 3). Because scientists are employees, and administrations are employers, administrations’ interests will always have the upper hand. This is the means whereby academic scientists are reduced to being generators of revenue, not agents of discovery.

Figure 3. Bundling indirect costs with costs of basic research puts the interest of institutions—pursuit of revenue—into conflict with the interests of scientists—pursuit of discovery.

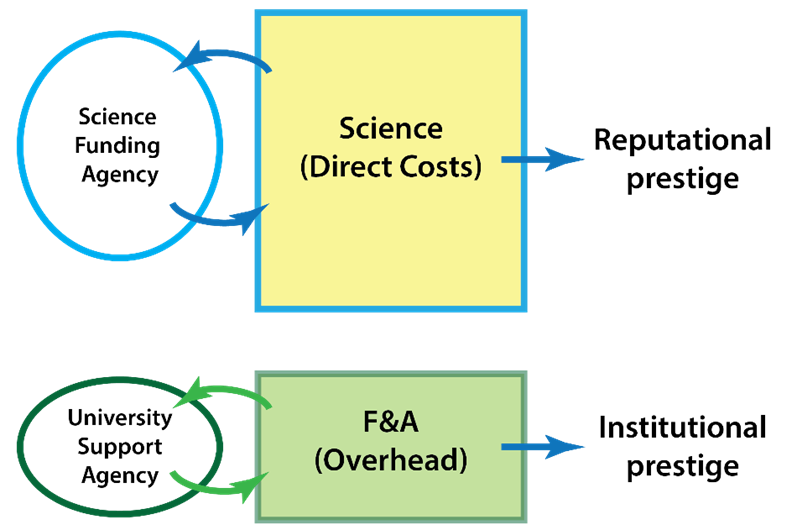

Overheads are a real thing, but there is no reason why they should be covered as they presently are. Separating overheads from research funding could allow the interests of scientists and their universities to be realigned in parallel rather than in opposition. The pursuit of prestige rewards could be one of the focuses of constructive alignment. This largely describes the relationship of scientists and their universities before World War II. For example, the pursuit of prestige rewards was a significant driver of the development of particle physics. In the 1930s, MIT, Harvard, Yale, and UC Berkeley were engaged in a competition to become world-class centers for physics research. Berkeley was, at the time, a physics backwater, but it lured leading American physicists like Robert Oppenheimer and Ernest Lawrence to their campuses and kept them there, even as competing universities dangled lucrative job offers to lure them away. Science was well-served thereby: this is how the cyclotron was developed.

The specific prestige rewards differed. Lawrence, Oppenheimer, and others wanted to be recognized as world-class scientists on the path to the ultimate scientific prestige award, the Nobel Prize. Their university administrations wanted to be seen as world-class centers of particle physics because that would bring in revenues and influence. Though the specific rewards differed, the interests of both scientists and universities were aligned, with science being the winner.

Realigning the interests of universities and their scientists could come about by decoupling overhead from research (Figure 4). Scientists could, for example, still submit research proposals to a science funding agency, but now universities could apply for a subsidy of overheads from an entirely different, and independent, revenue stream.

A third source of entanglement is built into the research contract model for research grants, which traps scientists into a cumbersome, overly bureaucratic, and arbitrary process that is wasteful of resources and scientists’ energy (Figure 1). Any solution for this form of entanglement would restore the original intent behind the mid-century proposal to federalize the academic sciences. More importantly, decisions on what research to pursue and allocation of funds to pursue it should be put more strongly in the hands of scientists themselves and not university administrations.

Figure 4. Separating funding for research from support for institutional overhead would align scientists’ and institutions’ interests toward pursuit of prestige.

There are various funding models that come close to these aims, even when it is government that is providing the funds. The Department of Defense, for example, maintains a variety of research funding programs, like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Naval Research Office (NRO), and the Army Research Office (ARO), which can circumvent most of the cumbersome procedures of the NSF and NIH research grant process. The specific remit of agencies like DARPA, for example, is to look for innovative thinkers and ideas, and to provide them funds without forcing the scientists onto the grants treadmill. Full disclosure: some of my own research on swarm intelligence was funded by the ARO.

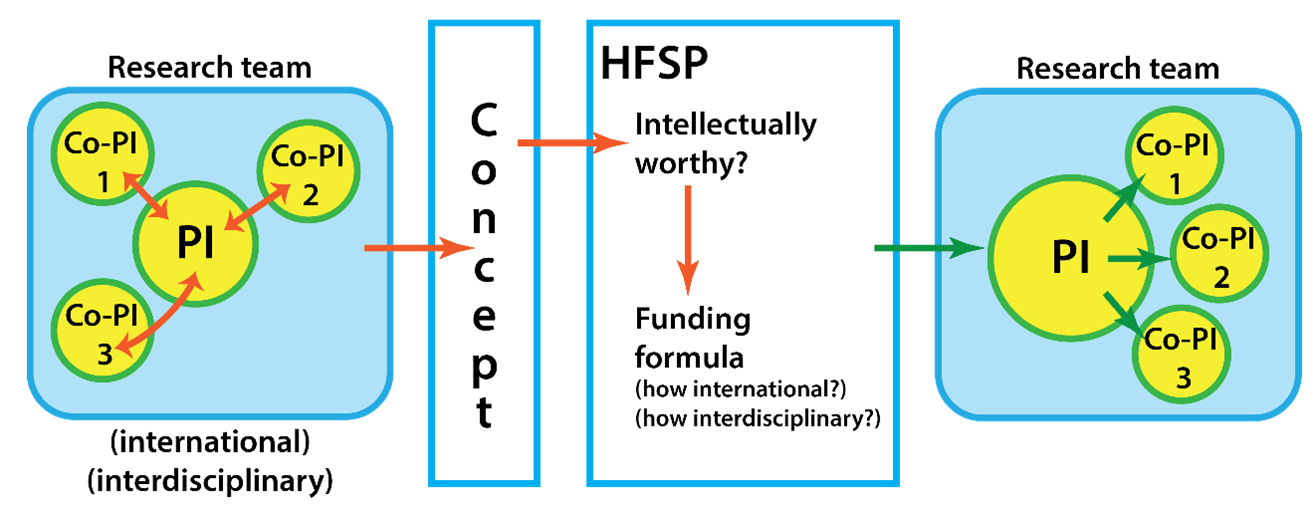

Figure 5. The HFSP model for funding innovative research.

Another model that encourages scientists’ autonomy is the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP). This is a multinational consortium of national science programs of several countries, including the United States, the European Union, Israel, Japan, South Africa, and India. The mission of the HFSP is to foster international and interdisciplinary collaborative research.

The HFSP does not fund projects, as typical research contract grants do, but interdisciplinary teams of scientists (Figure 5). To apply for HFSP funding, a team submits a short letter of intent outlining a broad problem to be explored. Again, full disclosure: I was the principal investigator on an HFSP grant, also on the broad problem of swarm intelligence. Once deemed compatible with the HFSP mission, teams are invited to submit a full proposal. Once granted, funding is not tied to a project budget, but rather upon the number of nations from which the team is drawn, and the different disciplines embodied in the team. The members of the team then decide among themselves, year by year, what promising new leads to pursue and how the funds are to be distributed among the team. Both can change year by year as the team decides. Importantly, the various universities involved have no say in those decisions. To decouple the funding of the science from the interests of their universities, indirect costs on HFSP grants are capped strictly at 10 percent of the year-by-year amount.

[RELATED: $15 Billion Saved from Indirect Costs Boosts Research]

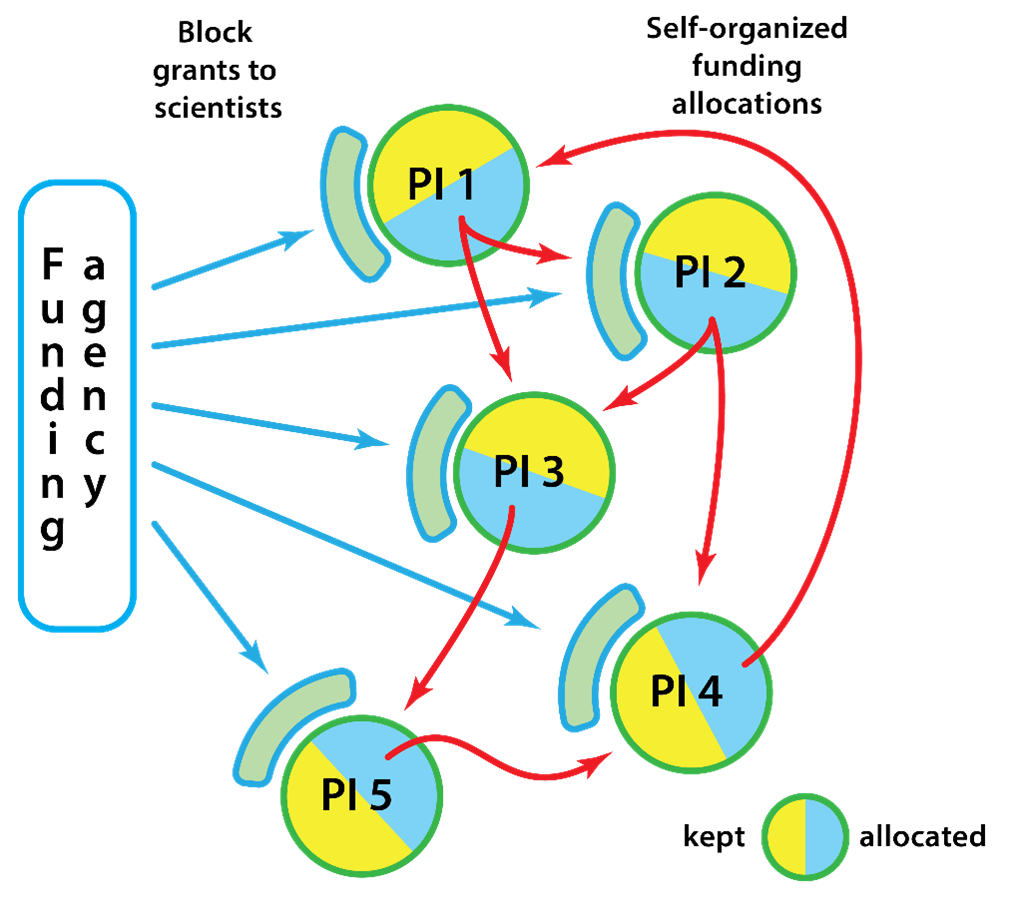

Self-Organized Funding Allocation (SOFA, Figure 6) takes autonomy a large step further. In this scheme, scientists—not universities—are provided a block grant that renews annually, and without a cumbersome application process. From those funds, a grantee is expected to allocate some proportion (say 50 percent) anonymously to other scientists that the grantee wishes to support. The allocation can change from year to year as the grantee decides, with appropriate guardrails against conflicts of interest, discrimination, or cronyism.

Figure 6. Scheme of self-organized funding allocation model for basic research.

SOFA has been proposed as a more efficient mechanism for directing funding toward promising areas of inquiry or to promising scientists. Scientists are liberated entirely from the grants treadmill because annual funding is assured. Allocation can be distributive, that is spread to several scientists, or aggregative, with resources directed to single investigators who the grantee deems as engaged in lines of research that are particularly exciting or innovative. Other criteria could apply. Younger, and hence more likely creative, scientists are poorly served by our current grants system. To correct this, the allocation could be directed explicitly to younger scientists. Or it could be directed established scientists who the grantee deems worthy of support. In all instances, decisions are firmly in the hands of communities of scientists, not science bureaucracies as they presently are.

Given the large numbers of scientists who would be part of such a network, SOFA comprises means of allocation that better reflects the ad hoc and fluid dynamic of basic science as it actually works, and puts funding decisions more directly in the hands of scientists themselves. Advocates argue that SOFA would also be considerably less costly in time and resources that currently go into developing, writing, reviewing, and administering the current system of project-oriented research funding.

To my knowledge, SOFA has never been implemented. Other proposals, like the DARPA model or the HFSP model, are welcome alternatives, but are not the norm for academic science funding. If academic science—and scientists—are to return to their prime mission of basic research, models like DARPA, HFSP, and SOFA need to become the norm, not the exceptions. The taxpayers who support the funds would now get what their money is supposed to do: support discovery in the nation’s universities.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Image by E on Adobe Stock; Asset ID#: 1356910661

An excellent essay in a number of dimensions. There is obviously otherwise some quid pro quo embedded in current federal challenges to R1 research activity. Regardless of how the challenge materialized, it has however initiated some awareness of closed university accounting practices at an institutional level, while raising questions at strategic levels of purpose, and operations questions as to efficiency. There is clearly a “lean management” argument implied, especially as to university overhead cost distortions (not just percentage, but burden). Like the federal government, universities operate at extraordinary levels of inefficiency. University of Chicago economist Robert Topel calculated that the ratio of federal tax receipts to measurable benefit related to carbon, is up to 250:1 (in my view this still understates the problem for both government and universities). That is, government overhead cost is so high that it takes $250 of tax to make $1 of benefit, and even then, “benefit” is subject to controversy (see https://bfi.uchicago.edu/insights/becker-brown-bag-some-dismal-economics-of-climate-policy/). Otherwise, university research economics may improve from converting “grants” into “investments” and thereby altering the character and expectation of funding, by directing it to expected return criteria. Like venture capital, most investments will “fail” but that is the nature of discovery; the failures will provide data and recovery knowledge. Moreover, very few universities have a complete funding system in place that includes specific commercialization as a next step beyond whatever may be deemed as research. Stanford is an example of the benefit created by adjacent private equity and commercial business development (Silicon Valley). Another bright spot may be in Illinois with a new quantum research park, and joint venture between the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and the University of Chicago. These types of more complete finance “ecosystems” seem to provide higher levels of expected research utility, where most research otherwise languishes or spoils. Otherwise, universities are vulnerable to systematic corruption of the scientific method via federal and foundation research, and will suspend statistical significance testing if certain activities are attached with reward. Biosecurity is an example, although not outlying.

The author fails to mention “swarm intelligence” has direct military applications, the obvious one being very small drones acting as a swarm towards a military target (think of Hitchcock’s “The Birds” and a flock of birds simultaneously changing direction in flight through the application of such intelligence). So naturally DOD or other military organizations will fund this type of research. But most scientific research does not have military applications.

The reason the US started funding science in the 50’s was because of military applications, and most money went to defense related projects (physics departments and laboratories cleaned up). With the establishment of the EPA and Nixon’s “war on cancer” money increasingly was diverted to “softer” sciences–environmental science and biology.

A relatively small amount was (and is) diverted to the social sciences–for example, before NSF eliminated the political science directorate a few years ago it was only 10-20 million/year. It is likely that the relatively small amount spent on the “soft” sciences (the studies and their ilk) made those practitioners eager to get their hands on the vast majority of money allocated to the physical sciences. So we get Broader Impact statements and DEI allegiance. But note Broader Impact statements originally were socially neutral–a standard joke among biologists was that it was necessary to add something like the phrase “this will help cure cancer” to a grant in order to get funding.

Regarding the various proposals the author makes, there are pluses and minuses to all which I won’t go into. But note the Trump administration wants to basically halve the research funding from the government, putting us in a similar position as other G7 countries. But most innovation in the US comes from government spending (the internet was a DARPA project, and it has transformed the world). While the methods of allocations should be reformed, it should not be cut, if we want to maintain American superiority throughout this century.