Editor’s Note: The following is an article originally published on the author’s Substack the Art of Science on August 10, 2025. With edits to match Minding the Campus’s style guidelines, it is crossposted here with permission.

On the bookshelf in my academic advisor’s office sits a beautiful burgundy cloth-bound book from the 1890s. With a finely textured cover and gilt lettering along the spine, it is one of those publications where the technical precision of the written word stands juxtaposed against the exquisite artistry of hand-drawn renderings.

At first glance, this might sound like a description of a classical literary work, such as The Secret Garden or Dracula.

An understandable, but erroneous, assumption.

As it happens, this book is an anatomy publication. The narrative—scientific text. The illustrations—anatomical diagrams.

It is always a treat for me to flip through that book. I could get lost for hours in the pages—those that come alive with detailed elegance, calculated finesse, and refined intricacy. Although there is nothing wrong with the modern-day printed anatomical atlas, nothing compares to the meticulousness and complexity of classic, hand-drawn graphics.

When science coexists with art, it becomes a flashback to the Humanities—the Renaissance Period, to be more precise.

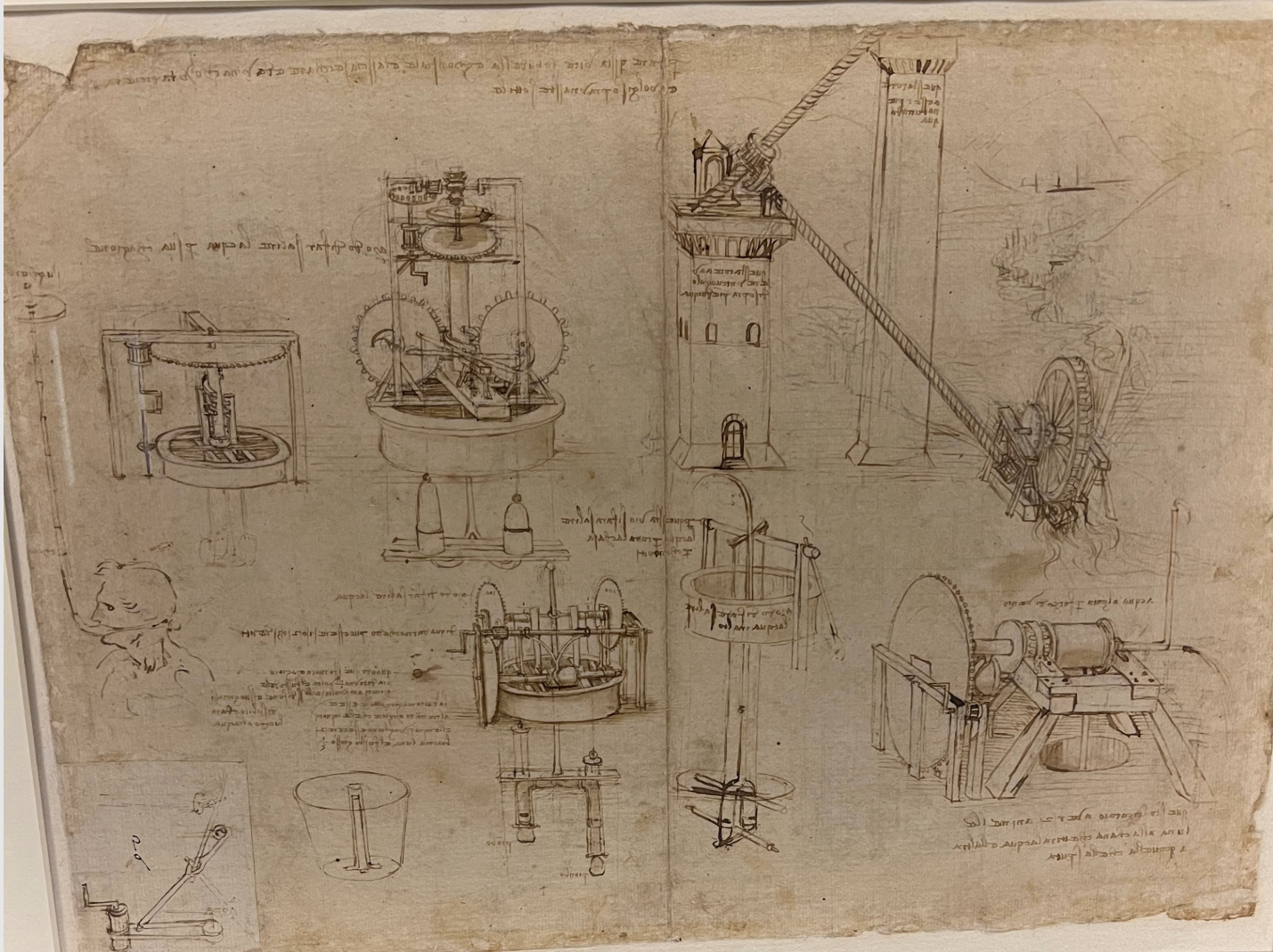

During this time, Leonardo da Vinci interfaced human anatomical observation with artistry, producing works such as the Vitruvian Man. Galileo Galilei studied astronomy by creating elegant drawings of the stars, found in books such as Sidereus Nuncius. Filippo Brunelleschi designed beautiful architecture, such as the dome of the Florence Cathedral, using mathematical principles.

However, the school of thought that prevailed during the Enlightenment began to set distinctions between art and science, and by the 20th century, the once seamless relationship between these two fields had relatively waned. In the 1960s, neuroscientist Roger W. Sperry’s split-brain experiments led to the development of the left vs. right brain theory. This notion, albeit oversimplified and somewhat fallacious, suggests that individuals generally favor one side of the brain over the other: either the “logical and analytical” left side or the “imaginative and abstract” right side.

Nevertheless, not everyone from this time period had lost sight of “the art of science.” Isaac Asimov evidently understood this concept deeply, evidenced by the following quote from the chapter entitled “Art and Science” in his book The Roving Mind:

How often people speak of art and science as though they were two entirely different things, with no interconnection. An artist is emotional, they think, and uses only his intuition; he sees all at once and has no need of reason. A scientist is cold, they think, and uses only his reason; he argues carefully step by step, and needs no imagination. That is all wrong. The true artist is quite rational as well as imaginative and knows what he is doing; if he does not, his art suffers. The true scientist is quite imaginative as well as rational, and sometimes leaps to solutions where reason can follow only slowly; if he does not, his science suffers.

For those of you who don’t know, Asimov was a 20th-century biochemistry professor and science fiction writer. He co-founded the highly respected Asimov’s Science Fiction literary magazine, which remains one of the most prestigious publications for science fiction writers.

Today, the interface between art and science seems to be regaining traction, with boundaries between these disciplines once again softening. And the re-fusion of the two disciplines is manifesting in unexpected and fascinating ways. The advent of STEAM—STEM with an added “A” for art—is evidence of this renewing interest. Medicine is exploring art-related therapeutics. Architecture continues to lean into the interface of beauty and function. And stunning electron microscope images are making their way into art museums.

The journey of “the art of science” is not just cultural. It becomes a personal identity among those who lean into it. I speak from experience.

I was inspired to create this Substack to explore the interface between beauty and technicality because I live this life every day. I am a biomedical science master’s student with dreams of becoming a scientist and academic. And I am also a journalist, a science fiction writer, and a former preprofessional ballet dancer.

I read scientific articles and find art in the figures. I observe artistic craftsmanship and discover mathematics, or the science of the human mind. I infuse technical concepts into my science fiction. And I bestow a literary voice on my scientific work.

Moving forward, I hope I am able to share with you my passion for “the art of science,” demonstrating the beauty of integration between these two seemingly distinct fields. I am looking forward to this journey with all of you!

Visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Photo by Jared Gould of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings, taken at the Leonardo da Vinci art exhibit at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C., June 2023.