Editor’s Note: The following is an interview with Minding the Campus contributor Joe Nalven, published initially on Harald Johnson’s Substack, Create or Die, on August 20, 2025. With edits to match Minding the Campus’s style guidelines, it is crossposted here with permission.

Joe Nalven is a creative, artist, instructor, and writer based in San Diego. He covers a wide range of visual creative fields, including photography, digital art, video, and more. Harald caught up with him recently to get his thoughts on the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and the creative process.

HARALD: You’ve been an advocate of using digital tools for art since the early 2000s. Can you talk about how things—for the creator—have changed? And show us some examples of that in your own work?

JOE: I began as a self-taught, cut-and-paste collage artist using magazine materials. That was the late 1960s. Much later, I used my own photos in my collages. It was not until the end of the 1990s that the service bureau I used to enlarge and print my collages on poster board finally refused to scan and print my small collages into large posters. They told me, “You are the artist. You have to learn Photoshop.” That was the impetus to learning how to use Adobe’s photo-editing software. I was not fully aware that the evolution of Photoshop ran parallel to learning how to print images on evolving inkjet printers. It was an amazing time for digital artists.

In the early 2000s, I joined other computer art enthusiasts and joined our nascent Photoshop User Group in San Diego. This proved to be a way of sharing new techniques. And from there, several of us formed the Digital Art Guild. We wanted to exhibit our digital art—even if it was only one percent digital. We did not just want to learn new techniques. From time to time, invited guests would demonstrate something new. Jack Davis gave us free workshops, energizing us to try new technology. Once, after showing us his digital camera that he converted into taking infrared photos, I immediately went online to B&H Photo to buy a new camera and had them mail the camera off to Life Pixel for conversion. (See Eilat Aquarium Attendant below.)

Since I am an eclectic artist, I look for possibilities. I am opportunistic. Part of what I look for is new technology, sometimes traveling to distant lands, and it is also how I process the image (primarily image editing tools) and then, if the image is compelling, expressing it with different media—paper, metal, lenticular, glass, and video.

A sampling of Joe’s images before using AI:

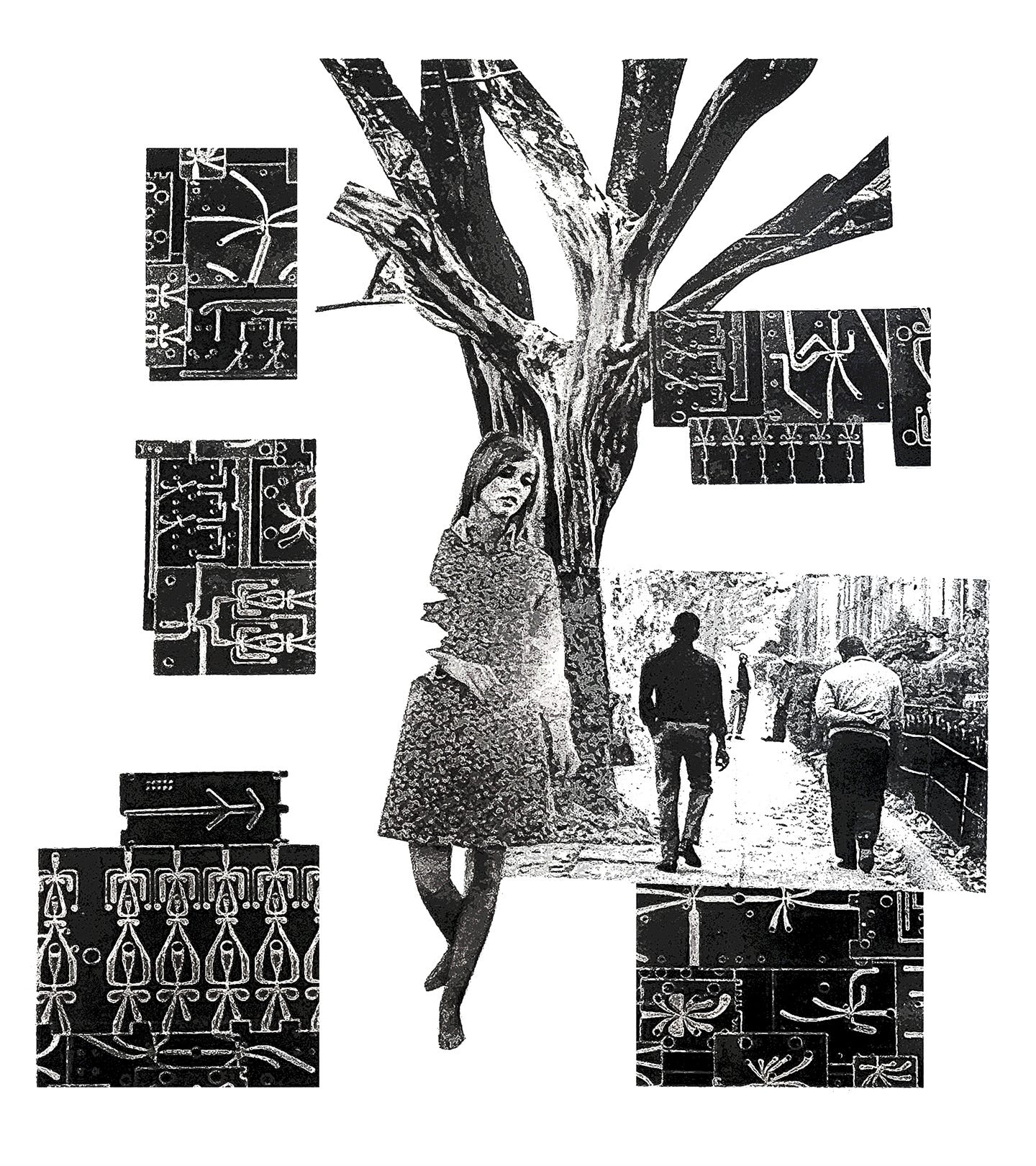

Late 1960s, cut-and-paste collage using magazine materials:

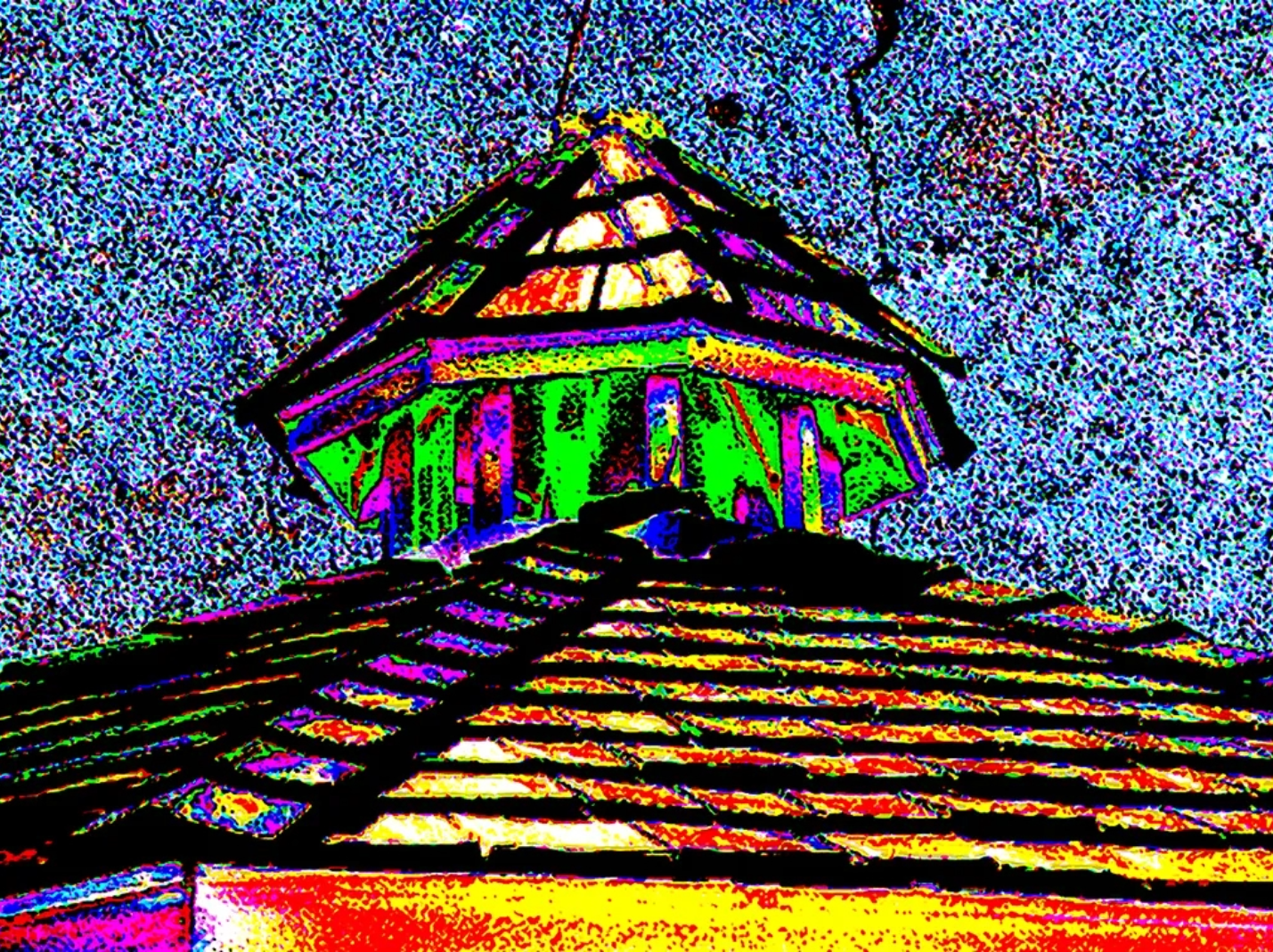

Early 2000s collage with personal photos, heavy use of the Photoshop curves tool:

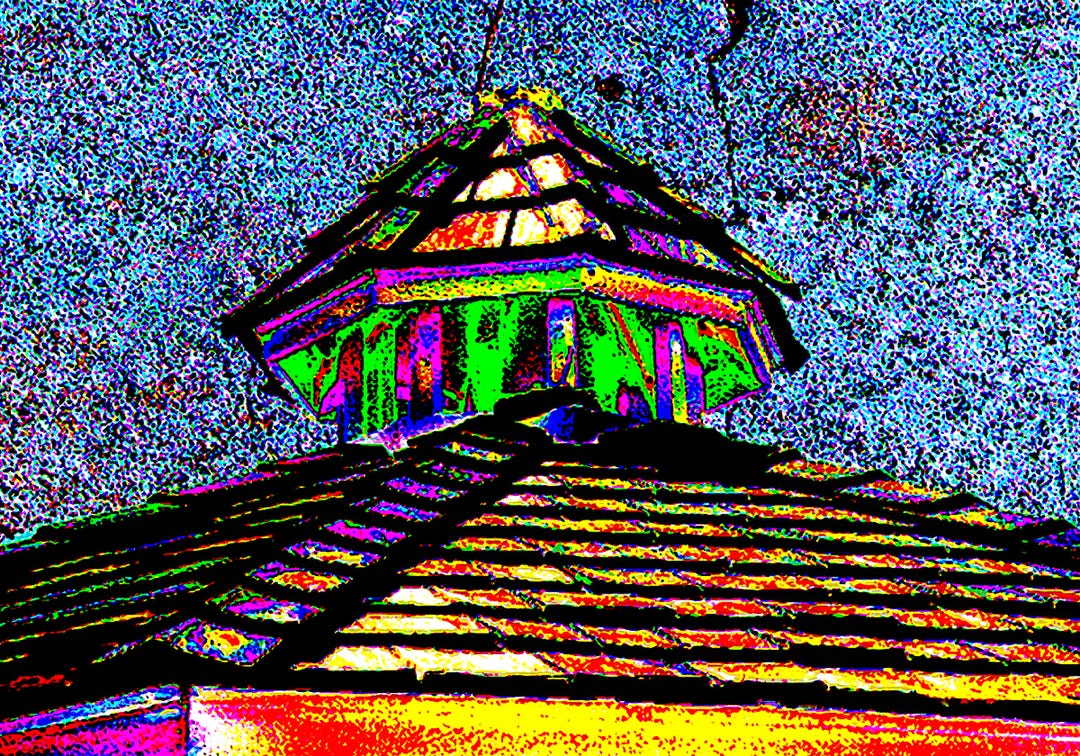

Crack in the Sky (Art Journal, 2009). My first photo collage using Photoshop: a gazebo with the sky from a photograph of a painted sidewalk.

SIGGRAPH Art Gallery (2007): Immigration theme, collaged in Photoshop:

Digital infrared photograph (2007) edited in Photoshop:

Eilat Aquarium Attendant

Mid 2010s – Stylized photography with Photoshop:

Screenshot from music video (2015) that was repurposed several years later with fused glass:

Joe: Both. We are in a period of transition with this new technology. And it’s not just about making art. There are problems of short-circuiting the creative process, de-skilling, and being trained on the work of others, past and present. At the same time, there is so much investment that one can only imagine how it will infuse so many aspects of our lives, as well as what we call creativity.

I have no control over these cross-currents, but I can experiment with generative AI as part of my workflow. I have a user perspective with scant knowledge of what goes on inside the AI black box. I’m trying to get a sense of how it can lead me into unexpected images. The challenge is getting past the too-cute, the too-glam, and the too-perfect.

Joe: Opinions about art and artists can trip over how we define and validate art and artists. I have encountered many curators and other artists who have said that digital art was simply a matter of pushing the button on a computer. That’s how many see AI art. The issue is further complicated by how art and artists are understood in different cultures, historically and across the globe. I have no good answer to this question.

However, AI does help craft an interim answer. We, humans, want to be unique. We share emotion, perception, mobility, and being in the world with other sentient beings. What makes us different or unique is somewhat tautological. Art is a human endeavor because humans do it. AI has humanity in its inner workings. AI has been trained on human words and human art. So, when we use AI, we are using it against the backdrop of all of humanity on which it has been trained. This is quite different from the other tools we use—the paintbrush, the camera, the chisel, and even software. With generative AI, the puzzle is how human artists keep themselves in the loop, making oneself and the AI elements part of a workflow that is tailored to a specific artist. As with all creativity—following Arthur Koestler in his book The Act of Creation, 1964—it is about informed play; that is, an individual’s maturity within a field—be it mathematics, physics, or art—and being able to play with the concepts and elements that exist in that field. That’s a bit long-winded, but it’s a tough question. What do they say about creativity—it’s one percent inspiration, 99 percent perspiration. That’s the same with using AI in making human art. By the way, AI doesn’t perspire; it is organized around data and algorithms. That is the black box for me.

Joe: There are different ways that AI can be used as an enhancement to human creativity, including art. An important caveat to this discussion is the continued evolution of AI models and the growth in applications to real-world activities. So, replacement of human creativity may be incremental. Something we don’t notice. I am especially concerned about K-12 education as well as higher education. The AI tutor may be the path to replacement unless we educate students about enhancement versus dependence.

Let’s talk about art. If the artist uses text to generate an image, we might ask to look at that text and its various edits; if the artist uses one image with a clip interrogator to generate the text, we might look at the original image, the AI text description, any human edits and then the new image; if the artist is generating an AI image and then superimposing it over an earlier image as another layer in Photoshop, we might examine the montaging of AI and the other image; if a painter has generated an AI model that is based on his own prior paintings (i.e. David Salle) and he prints an image and then paints over parts of that AI version, we might look at the conflation of the two versions. And so on.

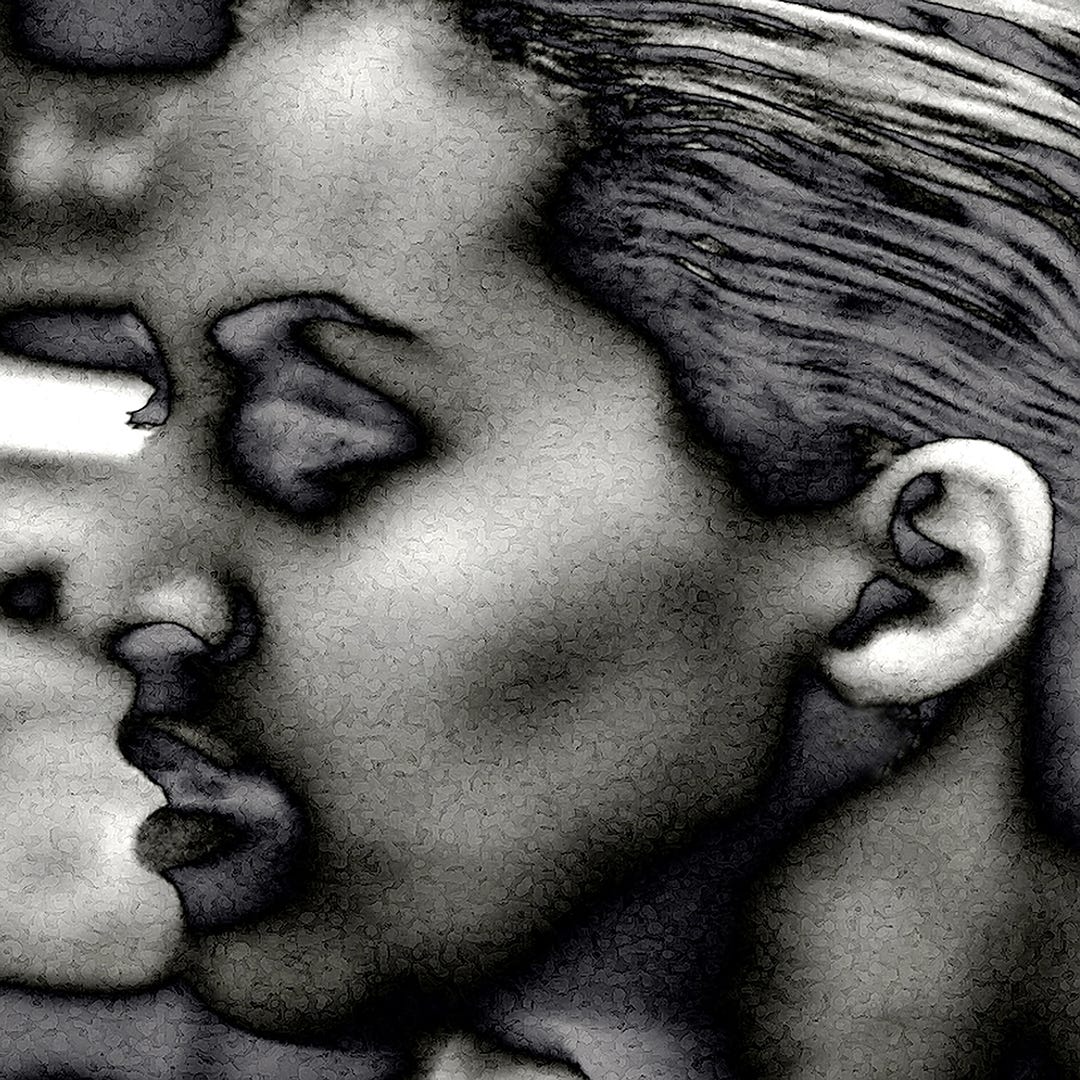

We often get stuck on the process of text-to-image iteration rather than other craftier ways artists can use AI in their workflow. The text-to-image process is generally transactional and likely to be used as a substitute for creativity. In a fast-paced commercial setting, that may not really matter. The more complex workflow requires a human to drive the artmaking process; it is generally transformational and more worthy of the creative label. That might well apply to how we see human creative efforts in general, not just with AI. Here are some examples from my own experience with AI:

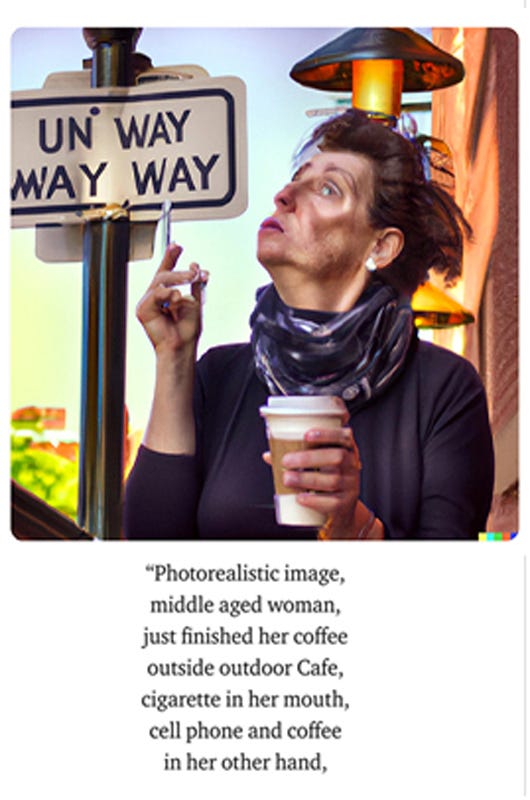

- A transactional image (October 2023) using OpenAI’s DALLE 2, which the company has since abandoned for DALLE 3. Text prompt is at the bottom.

Prompt: Since my experiments with DALLE 2, text prompts have become more complex, often by using an AI clip interrogator that “reads” an image provided to it. That AI text can then be used as a prompt in the same or a different AI model. Such improvements in AI-created text prompts has led me to include greater detail in the prompts I fashion myself. Also, the photorealism in AI images has significantly improved (if that is the objective). Embedded text is near perfect.

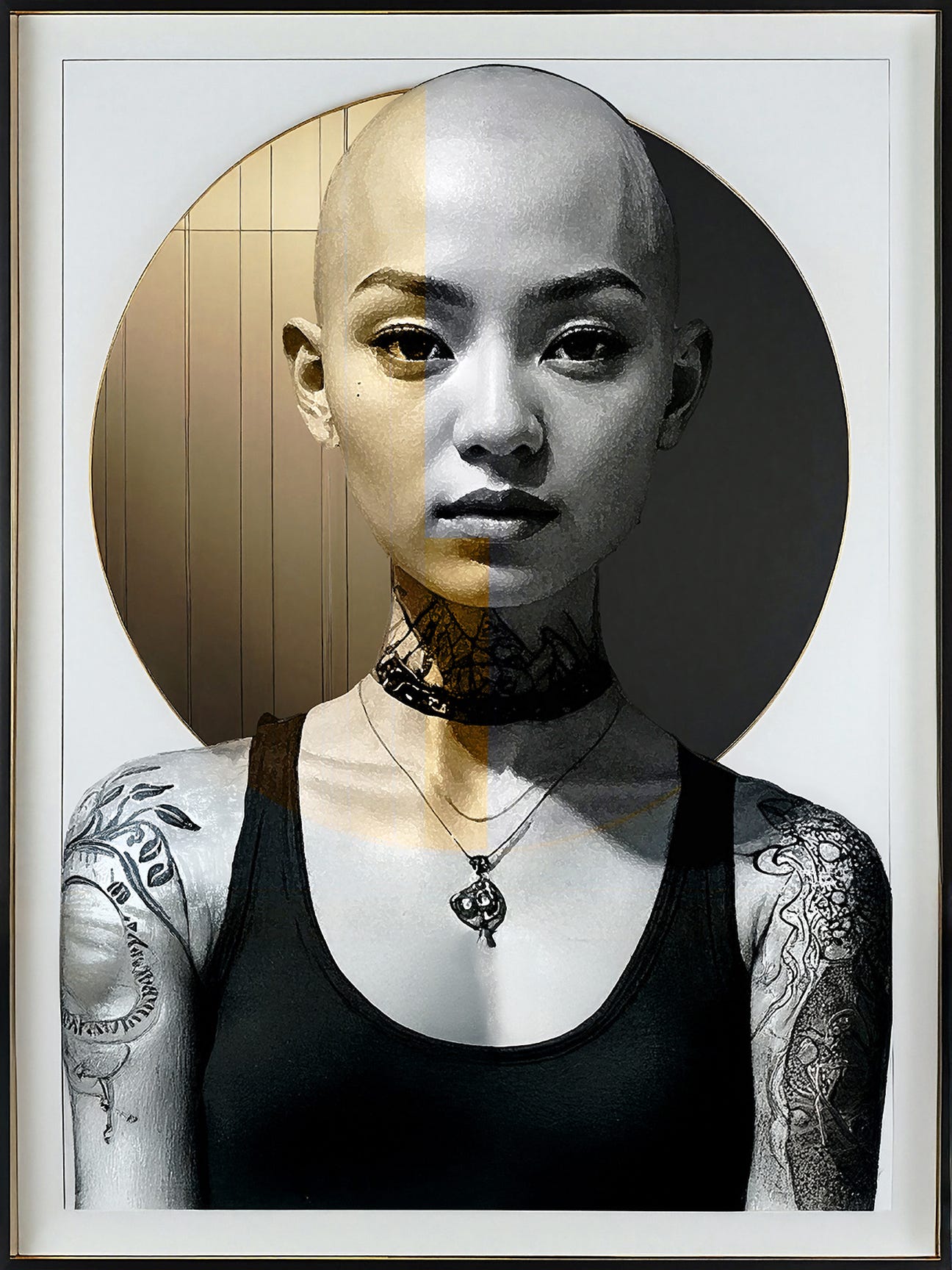

2. A newer transactional image, combining AI text and my edits. OpenArt AI, August 2025.

Prompt: Perched atop a flat roof, dancers and a weathered metal structure exude a sense of neglect and age, showcasing a patchwork of rust and peeling paint in hues of gray and copper. Surrounding and atop the metal structure are modern dance individuals creating an environmental dance. The boxy design, with a slanted roof, features an opening on one side revealing a glimpse of tangled wires and machinery within, hinting at its former utility. Surrounding it, the flat roof is a muted gray, contrasting with the textured surfaces of the structure, which implies exposure to the elements over time. The overall composition captures a gritty, industrial aesthetic, evoking feelings of urban decay and the passage of time, as this forgotten utility waits silently on the rooftop.

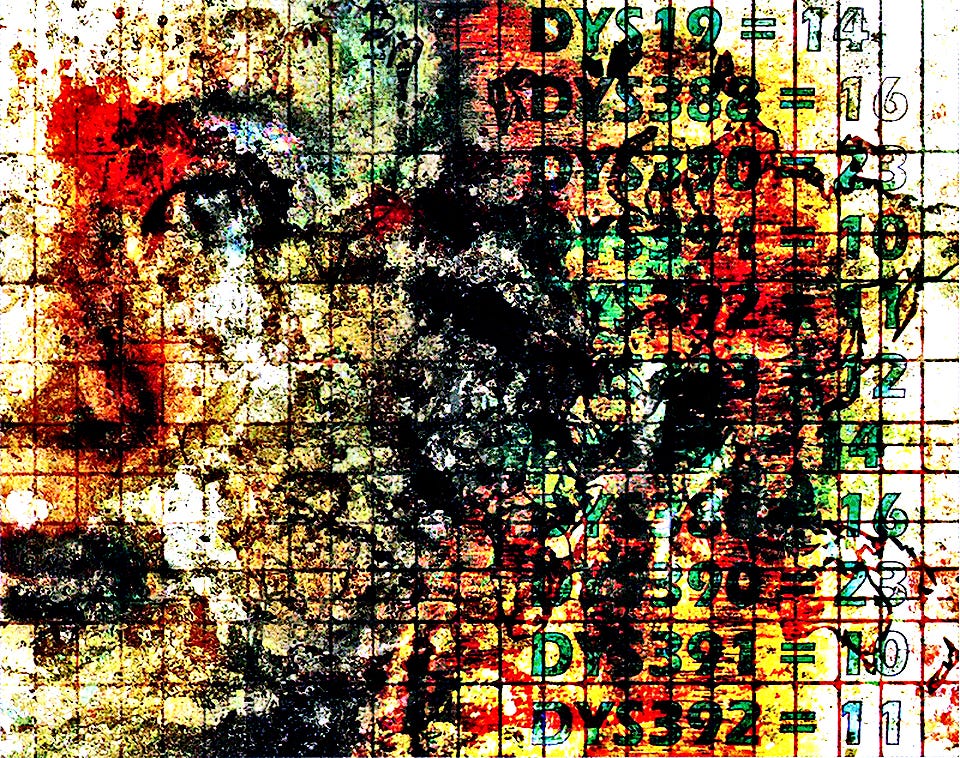

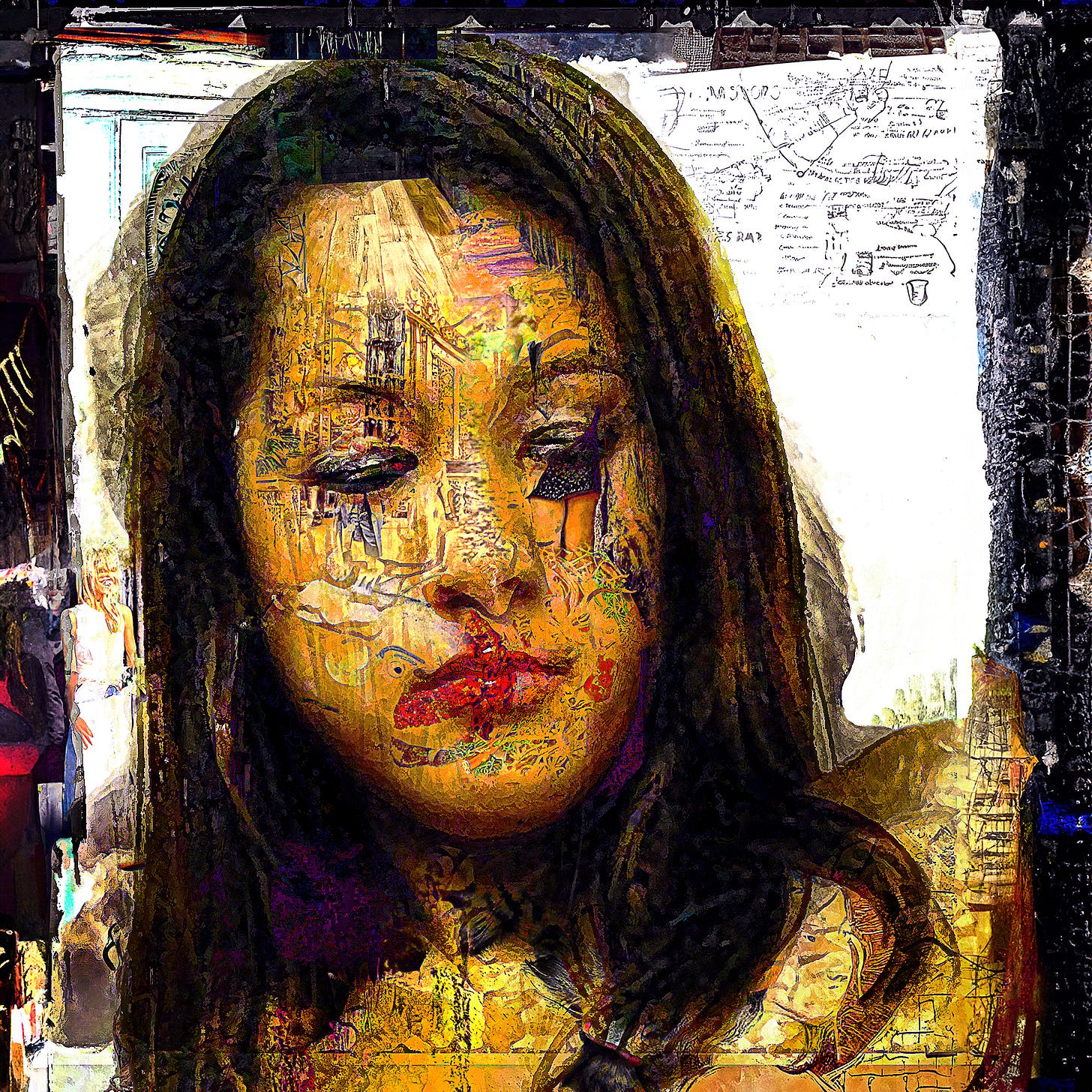

By comparison, the next image is transformational. I wanted to repurpose my original photograph in some way. Instead of using Photoshop filters to make it look painterly, I opened the image in Stable Diffusion, which I had downloaded to my desktop. There are any number of algorithms that generate different “stuff” as well as image variations. I copied one resulting “stuff” and superimposed it over the original photograph in Photoshop. In effect, I created a filter that was tailored to my original photograph. It would make little sense for anyone to copy this particular stuff since it would not be tailored to their own image. Perhaps viewers might see this as uglifying the image, preferring the original portrait. However, reimagining portraiture in the 21st century with AI tools can take the artist and the viewer into unexpected styles.

3. Original photograph montaged with AI oddments or stuff (Stable Diffusion) layered in Photoshop, early 2024. Transformational use of AI.

Joe: Transparency is key. If we let the viewer know how much AI has been used in the artwork, they can decide for themselves the artistry and ethics on which it is based. This may not be a sufficient framework, but so much is up for grabs in determining these questions. It might just be something that the viewer can decide if it was fair. Recall that Picasso used African art styles in his artwork (Les Demoiselles d’Avignon); he also said that good artists borrow while great artists steal. Stealing ideas is not copying; it is taking a style or concept and repurposing it for a new purpose. This is not quite the same as using AI that has been trained on the art of others, but it asks us to consider how much we stand on the shoulders of others, how creativity is about reworking longstanding ideas and materials, and how difficult it is to step away from jealousy in criticizing new techniques and new tools.

Joe: Let me start with the unexpected. I occasionally sit with my two granddaughters, three and five. They tell me a story that I input into an AI model on my mobile phone. “The lion is jumping on the bed with a toilet on its head.” And presto. Several responding images pop up. They laugh and want me to send it to Mom. I find this more satisfying than playing with Barbie dolls. And it is different than reading a story or playing Uno. The point is that AI technology has untold applications that can be used in novel ways.

Explore, try it out. I’ve written about a dozen articles (for Minding the Campus, Times of San Diego, and other outlets) that explore the boundaries of using this technology, as well as its potential to lead to unexpected consequences. Sometimes it is rejected by others. Fairly or unfairly. Take the San Diego County Fair with its photography and digital art exhibition. The lead staff rejected any AI images, even if it was labelled as experimental. They feared litigation if a direct connection could be found between an AI image and one that it had been trained on. They also acknowledged being technically unable to evaluate what was AI and what was human across different edits. By contrast, the Escondido Arts Partnership was open to AI-generated images—so long as the artist was transparent about his or her use in describing the media used to create the image.

Here is an image from EAP’s “Summation” exhibit last year:

Joe: I enjoy collaboration in putting together and participating in group shows. And also discussing art making. However, I go solo when it comes to making art—it’s about being in the zone, about not being interrupted, about getting lost in time.

Joe: Getting the image from the computer onto media is a different experience. Very analog. Putting an image onto fused glass became a multi-step process. Just printing the image on glass and then putting it into the kiln wouldn’t work since the inks would burn off during the firing process. Yes, there is a printer that can use ferrous oxide to print an image (a sepia result); and I’ve heard of printers that use ceramic inks but these were not available to me. Instead, I used a reference image below the glass on which I placed fritz, stringers, and other objects that could be placed in the kiln. (I did not do the actual firing.) When that piece of glass was fired, I took it to a print shop that had a flat-bed printer. The glass was turned over, and the image was printed in reverse on the back. When the glass was turned over, it looked as if the image was part of the fused glass. An analog workaround—trompe l’oeil. Putting images on distressed metal was equally arduous. And unique.

I also like to cook. Very analog.

Joe: I’d rather say moved or inspired to create rather than compelled. For me I feel compelled when I put together an image catalog. Then, I am working with product expectations and a timeline. However, being moved to create lands me in a time and space that is flexible and permeable, without the pressure of real-world boundaries. I suppose I could call being inspired as being compelled by my own interests. I would like to separate that personal drive from an outside requirement to create. Good question. When you ask about the no-matter-what situation that comes about when I get some notion, something that bugs me. I let it percolate. It may be a few hours, a few days or a few weeks. I think about the detective novel I wrote. It took me thirty years to publish. Once I settle on a reasonable endpoint to my imaginings, I lay out a game plan. I might have to figure out the materials and process. And my ideas might change in the process. There’s a flow that begins, a slippery slope that doesn’t end until I finish whatever I had first imagined.

Yes. It is easier with AI models on my phone. These images are mostly about fun and experimentation rather than more complex images that I create on my desktop. By the way, my seduction into AI led me to buy an Alienware computer with a gaming processor. I may not use it that often, but I am prepared.

Harald: Thanks, Joe!

Art by Joe Nalven