Academia is best understood as a social institution that thrives on what the French-American polymath Rene Girard called mimetic desire. According to Girard, humans are born with biological drives that steer us towards what we need to survive and procreate; however, beyond subsistence, our desires are shaped by the culture and models around us. The models, also called mediators by Girard, demonstrate the desirability of things as diverse as foods, clothes, cars, publications, peer citations, and even political and religious beliefs. In other words, we often learn that something is desirable because we see other people desiring it.

Girard outlines two distinct ways in which our desires are mediated: external mediation and internal mediation. In the case of external mediation, we draw our desires from models that we have little chance of interacting with because they are distant from us in time, space, or social prestige. This is why advertisers hire famous people to endorse their products and services; the odds that their consumer base will ever meet these people are slim to none. People can purchase the endorsed goods or services without risking a rivalry with the celebrity. Internal mediation, conversely, occurs when people in the same social world strive for the same ends using the same means. The result is, predictably, rivalry and conflict.

Girard calls the step beyond rivalry produced by internal mediation “metaphysical desire.” This arises when mimetic desire intensifies to the point where a person no longer just wants what their model has, but wants to become their model. For instance, it is one thing to seek scholarly recognition like a professor, but quite another to want the authority to decide who is worthy of such recognition. The shift is from imitating the professor who writes the papers to aspiring to be the gatekeeper who grants the awards. Girard warns that metaphysical desire is especially destructive: it breeds resentment, which in turn fuels quarrelsomeness and conflict.

All of this seems fairly straightforward, but it has profound consequences when one considers institutional neutrality and the politics of higher education.

[RELATED: The Trouble with Our Founders]

As I wrote previously, our academic training prepares us for a career in an echo chamber. We are trained in the specifics of a discipline, and then we choose a smaller area within the discipline to specialize in. At this point, we select a dissertation chair who oversees a research project that closely mirrors their own approach. Given the difference in academic experience, the dissertation chair can act as a mediator for the graduate student’s desires. However, once the graduate student graduates and becomes a professor, the potential for rivalry and conflict increases. This is more likely if they are in the same department, competing for the same research funding, graduate assistants, and scholarly publications. One way academic departments avoid such conflicts and rivalry is by prioritizing the hiring of faculty who were educated at other institutions and whose research and teaching specializations complement existing departmental strengths.

Increasingly, some professors and former administrators have taken it upon themselves to push universities to take a public stance on the geopolitical issues of the day. Arguably, the intellectual class does have a responsibility to engage with cultural and geopolitical questions. Yet in recent years, they have undermined any credibility to do so: the administrative and professorial class has eroded its own authority by marginalizing dissenting perspectives, leaving much of its public engagement suspect and often taken lightly. While complete institutional neutrality is impossible, expecting universities to issue public statements taking sides in geopolitical matters courts disaster. It transforms the university from an external mediator above politics into an internal mediator actively involved in it. Political struggle operates under very different rules than the study of politics, and unsurprisingly, universities are not built to withstand an all-out political conflict—as the many concessions to the Trump administration demonstrate.

Universities similarly court disaster when they institutionalize values in the form of policies that are at odds with federal law. This is precisely what the University of California system did in the 2010s, when it decided to require an “equity, diversity, and inclusion” statement (EDI) in all hiring searches. This change was soon accompanied by a system-wide requirement that EDI be considered in all tenure and promotion decisions as well. Interestingly, the motivation for instituting these requirements appears to be mimetic desire. According to UCLA’s website, the motivation for requiring these statements in hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions was:

Much like a candidate’s CV, research statement, or teaching statement, an EDI Statement provides the hiring committee with relevant, useful information about a candidate’s qualifications and potential for future success … Ultimately, as peer institutions increasingly adopt these practices, failing to require an EDI Statement may signal tepid commitment to these values, which could put UCLA at a competitive disadvantage.

One may be forgiven for wondering how an EDI statement helps a search committee determine a candidate’s potential for future success. How does an EDI statement tell you about a candidate’s potential for effective teaching, garnering external funding, or internationally prominent research? It does not, but it does signal fealty to the value orientation the university system has adopted—and there cannot be success without this submission. The EDI value system has become literally institutionalized with the creation of EDI centers on California system school campuses. These centers now seek to remake the university in their own image. The EDI center at UCLA advertises as much, stating:

We work with the UCLA community and partners to advance an inclusive excellence framework for EDI through the following four dimensions,[inclusive leadership, education, engagement, and accountability] aiming to intentionally incorporate our values into UCLA’s mission, priorities and culture.

The EDI office at UCLA is, from Girard’s perspective, animated by metaphysical desire—it desires to be “the model” that all internal mediators look to. The result is that the EDI office is internally mediating campus offices, departments, professors, and staff. EDI is not another category employees are evaluated on; it is the framework through which the UC system evaluates all scholarship, teaching, and service. True, the system has revoked the requirement that applicants submit an EDI statement, but the requirement remains in place for tenure and promotion, which effectively means that new hires will be forced to engage in scholarship, teaching, and service that aligns with EDI.

[RELATED: Say ‘Yes’ to the First Amendment]

Here is an example from UCLA of how EDI statements might be evaluated. This rubric clearly shifts attention away from genuine interest and competence, directing students and faculty to focus instead on activities that advance EDI goals, since those are what matter for promotion and tenure.

Rather than upholding the dignity of all, as these centers purport to do, these changes to the university’s mission actively politicize academia, shifting the internal mediation from publications, teaching, and service to leftist political activism. Moreover, EDI is not politically neutral; its tenants are all leftist, meaning moderates and conservatives do not share them. To use EDI as the internal mediator for desire at the university is to incentivize the hiring and promotion of progressive activists—the more outspoken the better—and to categorically discriminate against conservatives and moderates. It is also to encourage intense conflict between colleagues based on identity differences and aspects of their identity that they cannot control, such as their race, sex, or the social class into which they were born, because these factors are considered when the university decides how to allocate its resources.

Under such a system, the result would be a deep sense of resentment towards those whose ascribed characteristics were valued more highly. Perhaps this is necessary to bring about the goals of EDI, but one is left to wonder if such an environment is conducive to the search for and communication of truth.

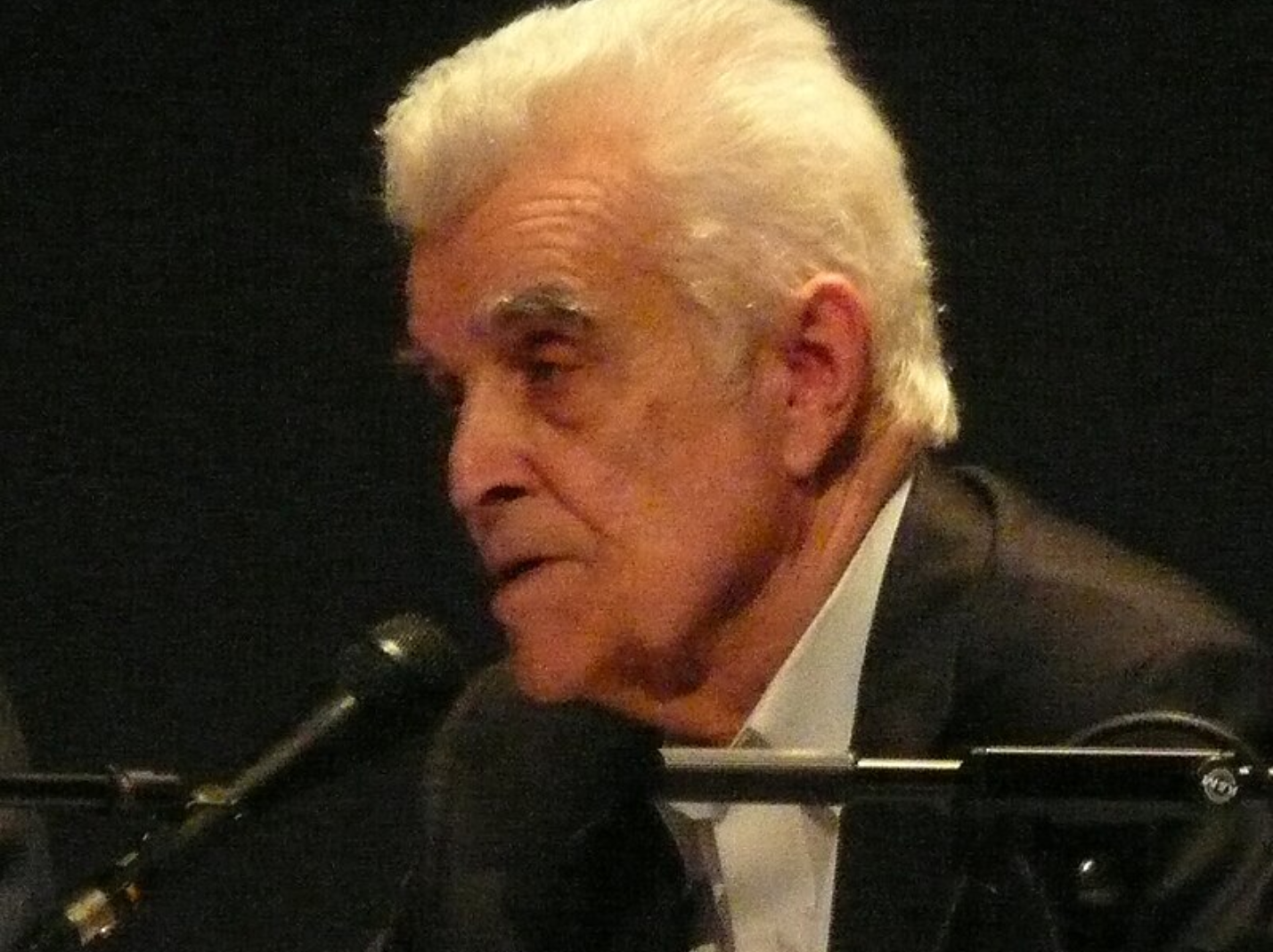

Image: “René Girard during a colloquium in Paris ‘End of war and terrorism'” by Vicq on Wikimedia Commons