I head an organization, the National Association of Scholars (NAS), that is often accused by its critics on the academic left of nostalgia for days when higher education was an exclusive club for the privileged. The accusation is false. NAS focuses on the enduring principles of the university: rational inquiry, liberal learning, and academic freedom. True, there have been points in the past when these principles have been better observed than they are today, but our interest is in the future of the university, not its past.

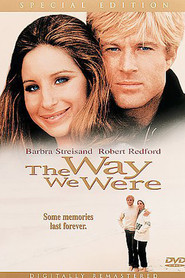

Thus I was eager to learn more when I heard that a group of professors had come forward to promote an ambitious “Campaign for the Future of Higher Education.” Alas, my excitement proved premature. It turns out that the Campaign is mostly reactionary. It was put together by an alliance of groups, mostly unions, fearful of current trends and desperate to halt developments that may well lead away from a recent epoch in which higher education was indeed “an exclusive club for the privileged.” The “Campaign for Higher Education” might be better titled, “The Way We Were.”

In January the California Faculty Association (CFA), a faculty union, convened a meeting of seventy faculty members, representing several other unions and other organizations, including the AAUP, the American Federation of Teachers, and the National Education Association. The Chronicle of Higher Education reported under the headline, “Faculty Groups Gather to Craft a United Stand on Higher-Education Policy,” that the attendees agreed to take back to their memberships a document drafted by the CFA that “outlines a set of principles it believes should undergird higher-education policy over the next decade.” AAUP president Cary Nelson indicated that the principles would be presented publicly in April in a series of teach-ins.

In mid-February, Jason Jones, writing on the Chronicle’s Profhacker blog, clarified that the key date is April 13, which has been designated “Take Class Action Day.” In case the radical intent is insufficiently clear in the double entendre “class action,” the event comes with its own bright red Marx-oid poster, showing a left-hand chalking up the slogan, Take Class Action!” Jones kindly explains that the image “was developed by the CFA and is free to use.” Well, OK.

Last week the AAUP wrote to its members urging them to participate in the April 13 extravaganza and also listing the seven principles that the CFA proposed and the AAUP apparently endorses. I am starting my teach-in a little early. Here are the seven principles and my comments.

Campaign for the Future of Higher Education: Guiding Principles

- Higher education in the twenty-first century must be inclusive; it should be available to and affordable for all who can benefit from and want a college education.

This is wish fulfillment. I would be glad to see higher education open to all who can benefit from it, provided that it is closed to those who can’t, and that we eliminate the loophole of offering so-called “higher education” programs that are remedial or consist of a congeries of intellectually feeble courses. If the “Take Class Action!” folks really mean by “college education” some form of post-secondary training that is “affordable to all,” there might be room for a broader discussion, but the only way “college education” can be fit to this demand is by hollowing it out.

As to those who “want a college education,” the phrase is curious. A great many students “want” a college education because they are the recipients of good marketing. They think, often wrongly, that it is their best option for a prosperous future. Many might “want” something else if they understood more clearly their options, the risks, and the balance of costs and benefits.

Any real plan for the future of American higher education will have to be grounded in economic reality. Insisting that it be “inclusive” and affordable for all is profoundly inconsistent with state and national public finance; with the ratio of college costs to personal income; and with the underlying cost structure of contemporary higher education.

- The curriculum for a quality twenty-first century higher education must be broad and diverse.

We would be better served by college curricula that are intellectually rigorous, coherent, focused on the most important bodies of knowledge, and fostering genuine intellectual inquiry. Our long-running experiment with “breadth” has in all too many cases devolved into over-specialization, the teaching of mere trivialities, and a turn towards ideological salesmanship. We could of course have curricular breadth in the more wholesome sense of curricula that aimed to give all students a secure foundation in Western civilization, world cultures, history, science, higher mathematics, books of lasting worth, disciplined writing, and command of the spoken word.

But I suspect that is not what the Take Class Action! folks have in mind. For one thing, to achieve that kind of breadth might well mean redeploying educational capital in a manner that favors the long-term interests of the students. Take Class Action! is about defending the status quo for faculty members by trying to prop up a system that is manifestly in financial trouble.

As to “diverse,” to the extent the word isn’t just a redundancy (“broad and diverse”), it points to the ethnic and special interest balkanization of the curriculum. The familiar logic here is that every identity group deserves its own cabined piece of the curriculum. It is perfectly understandable why people who have built their academic careers based on corralling students into identity groups based on their supposed history of victimization would want to keep that kind of “diversity” in place. If we are thinking about how best to serve the students in the twenty-first century, however, this sort of curriculum is a dead end. Majoring in group identity is preparation for a life that combines tokenism and resentment. We would be wise as a nation to retire this failed experiment.

1.Quality higher education in the twenty-first century will require a sufficient investment in excellent faculty who have the academic freedom, terms of employment, and institutional support needed to do state-of-the-art professional work.

Principles 3 though 7 each begin with the ad-copy truncation of the subject, “quality of higher education,” which ellipses “high quality,” and builds on an implicit metaphor of higher education as a consumer good, e.g. “Quality tobacco products on sale today!” The phrase is sadly revealing about the underlying attitude of the Take Class Action! folks.

Do we need a “sufficient investment in excellent faculty?” The idea is tautologically true. The question is, what level of investment would be sufficient? The evidence is pretty strong that it is an amount far below the current total paid to America’s 700,000 or so full-time faculty members, many of whom come nowhere close to “excellent” and many of whom teach in areas that could be eliminated tomorrow without any adverse consequences to the education of America’s college students.

I doubt, however, that the CFA, the AAUP, and their congeners are really calling for such a housecleaning. Rather, they are trying out a rhetorical appeal to increase the level of public financing for a special interest. The appeal may warm the passions of those who are worried about their personal prospects in a field of employment that faces significant retrenchment, but it seems unlikely to move the general public, which has drawn its own conclusions.

- Quality higher education in the twenty-first century should incorporate technology in ways that expand opportunity and maintain quality.

“Quality”—oh, never mind.

“Should incorporate technology.” Yes indeed. But the Take Class Action! folks hardly need to urge this development. If they are talking about distance learning and other electronically-mediated forms of instruction, they are happening on their own, and they will clearly “expand opportunity.” Anyone eager to learn can find an abundance of good curricular material and books for free or at minimal cost on the Internet right now. Those who are eager to acquire college credit for such study likewise have a range of low-cost opportunities as well as more expensive ones.

The hitch is in the CFA’s three-word phrase, “and maintain quality.” This might mean simply the benevolent wish that online courses be as good as in-person courses. More likely, it means, “and do this in a way that doesn’t threaten our employment.” If so, it won’t wash. Online higher education is, for better or worse, certain to displace large numbers of faculty positions in the bricks-and-mortar sector, even when it is carried out by the bricks-and-mortar institutions themselves. Some of the online courses, perhaps even many of them, will be of marginal value to students, just like some of the in-person instruction is now. The transition to a form of higher education in which a great deal more is accomplished online, however, won’t be impeded by the availability of junk courses. The market will sort itself out. And I expect that will happen with very little assistance from faculty unions and the AAUP.

- Quality higher education in the twenty-first century will require the pursuit of real efficiencies and the avoidance of false economies.

We need some additional detail to decipher this. “Efficiency” is a possible goal of higher education, though seldom understood as one of its highest. Harvard president Charles Eliot promoted the idea in 1909 in his little essay, Education for Efficiency. Eliot wrote that teaching needed to be judged by standards if was to be anything more than “trial and error,” and to make “teaching a rational profession,” we need measures of “personal culture and social efficiency.”

It is a telling indication of the mossback conservatism of the “Campaign for the Future of Higher Education” that it has turned back the clock more than one hundred years to find a rhetorical appeal against the progressive spirit of our times. Americans are asking for education that provides access to things of lasting value through forms of study that are reasonably affordable. The Campaign direly warns against “false economies.”

What might those false economies be? Would shutting down women’s studies departments at state universities be a false economy? How about eliminating the superstructure of diversity provosts, deans, assistant deans, and directors? Would phasing out post-colonial studies be a false economy? Or are all these off the table because they offer “real efficiencies”?

- Quality higher education in the twenty-first century will require substantially more public investment over current levels.

Really? What if “public investment” has already maxed out because the states are faced with massive unfunded pension liabilities, the federal government is trillions of dollars in debt, and the Chinese may be disinclined to keep lending to us just so that we can continue to live beyond our means? Just because we want something doesn’t mean we have the money to pay for it, or that the public is going to be willing to trade one of its other priorities—say, Medicare prescription medicine benefits—for a faculty union’s vision of “quality higher education.”

Of course, we can have a very good system of higher education in the United States without “substantially more public investments over current levels.” Those current levels, driven by the delusion of mass higher education, have had the paradoxical effect of driving down academic standards and luring millions of students into unnecessary debt. I don’t expect the federal government to extract itself from this mess anytime soon, but I do think it unlikely that Congress will substantially increase the public funds it currently squanders on higher education.

- Quality higher education in the twenty-first century cannot be measured by a standardized, simplistic set of metrics.

No one of course, favors “simplistic” metrics. The phrasing is tendentious in its implication that standardized measures are by their nature simplistic. In truth, some measures are simplistic, while others are sophisticated. The CFA crafted this list before Arum and Roksa’s book, Academically Adrift, reported on the dismaying results of their analysis of the Collegiate Learning Assessment. They showed, among other things, that 37 percent of college seniors failed altogether to advance their intellectual skills during their years of college study. But CFA no doubt caught at least some of the emerging scholarly discussion of evidence that college as we know it just doesn’t accomplish very much for a substantial portion of those who enroll.

I share the worry that we could as a nation stumble into using measures that run roughshod over some areas of inquiry. The liberal arts are vulnerable to crude utilitarian devices (often called “student learning outcomes”) for figuring out what students know. The Collegiate Learning Assessment, however, whatever its imperfections, is certainly not a crude device. I would welcome the emergence of something like national voluntary exams for college graduates who want to demonstrate true subject mastery. The college degree itself is now a notoriously unreliable indicator of student achievement, and grade inflation being what it is, student transcripts aren’t much better. But I rather suspect that the Take Class Action! folks aren’t especially eager to see the emergence of any form of testing or credentialing that could call into question the value of the current curriculum.

The Mis-Guiding Principles

The Campaign for the Future of Higher Education is, in short, a campaign to maintain the privileges and the positions of members of an occupation that faces a degree of historical obsolescence. The members of the occupation do not form a “class” in any meaningful sense. The “new class” of knowledge workers that sociologists such as Peter Berger used to write about doesn’t map neatly onto unionized faculty members. Rather, the faculty members are behaving more like pampered Detroit auto workers devoted to maintaining a system that produced overly expensive, low-quality cars that grew less and less competitive in the world market. Americans are awakening to the reality that we have a system of higher education that does, on average, a poor job at very high expense. We are looking for alternatives and the chances are very good we will find them. That has the unions scared.

April 13 is in effect their Halloween. Their members will dress up in costumed urgency and attempt to frighten Americans into supporting their program. Be kind. Throw them some candy. Just don’t get drawn into their nostalgia-fest.

To Peter Wood:

I just wanted to thank you for your six-month series of columns for the Chronicle of Higher Education, which were a refreshing antidote to the prevailing liberal orthodoxy that grips higher education today. Your insights and analyses have been spot-on and I commend you for your courage under fire. I trust more and more academics come to see that the road we have been headed down in recent decades is a dead end. Thank you for your role in articulating the pressing problems inherent in today’s university.

Best,

Dr. Richard Rankin Russell

Associate Professor of English

Baylor University