America’s colleges and universities are in trouble: falling enrollments, declining public support, even the beginnings of a decline in our dominance in international rankings. While many factors are at work, here are the top ten things I think are destroying America’s colleges and universities.

First, going to college is too costly. Tuition fees have roughly doubled, adjusting for overall inflation, in the last generation. They have risen faster than people’s incomes –a rarity in a country which has had economic growth almost continuously since its first European settlement in 1607. Total spending per student on colleges is significantly higher in the U.S. than almost anywhere else in the world.

Related: Five Reasons Why Students Loans Are a Looming Disaster

Second, the federal student financial assistance program is completely dysfunctional. The rise in tuition fees has accelerated, confirming the hypothesis of former Education Secretary Bill Bennett that universities raise their fees aggressively knowing students will simply borrow the money from the federal government –creating some $1.5 trillion in loan debt for well over 40 million Americans. Academic research shows Bennett was right – rising tuition fees funded through federal student aid has financed a destructive academic arms race that has given us fancy buildings and lots of high-priced academic bureaucrats. Meanwhile rising prices have led to a lower proportion of recent graduates coming from low-income homes than in 1970 –before federal loan and grant programs became large.

Third, student learning in the college years is very modest. The evidence here is less conclusive, largely because colleges collect little-standardized data on their main “output” – student learning. Yet Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, among others, have demonstrated that college graduates are not much better at reasoning or writing capabilities than newly matriculating students. Grade inflation is rampant –the average grade in the 1950s was about a C+; today it is approaching a B+. Why study if you are going to get high grades anyhow? No wonder the average student today spends fewer than 30 hours weekly on studies, compared with 40 hours around 1960.

Fourth, universities are infected with massive administrative bloat that raises costs and reduces the emphasis on “Job One”: teaching and research. At a typical school today, more individuals hold some type of non-instructional administrative role than are teaching. The “instruction” share of university budgets has fallen from around 40 percent in 1970 to below 30 percent today. As administrative power has grown, less emphasis is placed on creating and disseminating knowledge and more on politically fashionable objectives like reducing global warming (promoting sustainability) and achieving “diversity.”

Related: 900,000 Bureaucrats Work on Campus Today

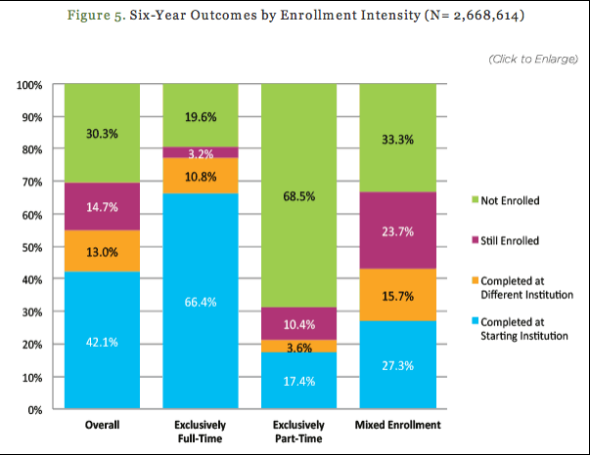

Fifth, a large proportion of students never graduate or take more than the expected four years. The six-year graduation rate among full-time students at all American universities is perhaps 60 percent, and more entering students fail to graduate in four years by far than ones that do. One reason is that many students are admitted to college with abysmal academic preparation (partly the fault of a mediocre system of public K-12 schools). The notion that “college is for all” contributes to many students failing to graduate –acquiring more debt than marketable skills.

Sixth, once bastions of free expression and uninhibited but civil debate, universities today often stifle dissent, discouraging lively dialogues about contemporary issues. Speech codes, “trigger warnings,” small free speech zones, disinviting or even shouting down speakers, and simply not hiring professors who deviate from the prevailing mostly leftish ideology are blights on many (but not all) campuses. Feckless university administrators sometimes are bullied by groups promoting the suppression of viewpoint diversity that is the traditional hallmark of a college education.

Seventh, good consumer information on student learning and performance are lacking, and the accreditation system is a national embarrassment. One reason for high failure rates is many students attend a school inappropriate to their aptitudes or interests. Do seniors at college X know more or earn more after graduation than those attending college Y? Who knows? Accreditation is broken: it is ridiculed with conflicts of interest, provides little information to consumers, concentrates on inputs rather than outcomes, is excessively complex (multiple institutional accreditors with varying standards, for example), and is too costly.

Related: Race and Gender Studies Kick Shakespeare Out of Class

Eighth, incentives to improve outcomes and utilize cost-saving technology are weak. In the private sector, we get ever better and often cheaper products like smartphones and quick delivery of purchased goods, and providers are richly rewarded. In higher education, we still teach largely the way Socrates did 2,400 years ago (and probably not as well). There are no big rewards for good performance, and, indeed, it is even difficult to know who is doing well and who is doing badly. The lack of market discipline and rigorous price competition and the protection of mediocrity by government subsidies adds to costs and detracts from qualitative improvements. Who are the Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs of higher education?

Ninth, facilities and other resources of universities are vastly underutilized. Academic buildings are mostly empty around four months a year. No one teaches on Saturday, and few even on Fridays anymore. We take months-long summer breaks, ostensibly to plant and tend the crops, reasonable perhaps in 1818 but not 2018. Professors are in the classroom fewer than 10 hours weekly for perhaps 30 weeks a year. Students spend less time on academics then they spent as young teenagers in middle school.

Tenth, intercollegiate athletics has become extremely expensive, exploitive, and often a moral cesspool at many universities. At some schools, over $1000 is spent annually per student to subsidize ball throwing contests thrilling alumni and the public but have little to do with learning. Talented football and basketball players earn a fraction of their worth in a free labor market, with the surpluses going largely to their coaches who often earn far more than the university president. Academic and even sex scandals are fairly frequent, lowering the reputation of American universities.

Other than that, things are fine!

“Ninth, facilities and other resources of universities are vastly underutilized. Academic buildings are mostly empty around four months a year.”

There is a lot of maintenance done in the summer. Entire systems — steam, water, electric, & computers — are shut down not only in entire buildings but often whole sections of campus. This is work that has to be done, and what surprised me was that steam is somehow necessary for air conditioning.

A university also must always be doing a lot of recruitment to replace not only those students who graduated but those lost to attrition, and some universities have a freshman attrition rate exceeding 30%. The dormitories and other student-service facilities are needed for this (and it has to be juggled around the maintenance schedules).

“No one teaches on Saturday, and few even on Fridays anymore. We take months-long summer breaks, ostensibly to plant and tend the crops, reasonable perhaps in 1818 but not 2018. Professors are in the classroom fewer than 10 hours weekly for perhaps 30 weeks a year.”

A college credit was once defined as one 50-minute class for 17 weeks, with a subsequent final exam. Classes were once taught on Saturdays, with those classes subsequently compressed into the 75 minute Tuesday & Thursday classes. And the 17-week semester has been compressed to what is sometimes only a 12-week semester!

That is 30% less teaching time than there was in 1918!

Worse, professors used to teach “4&4” — four classes each semester, or eight a year. By 1980, it had largely shrunk to “3&3” or six a year, and by 1990 it had shrunk even further to “3&2” or 5 a year — and now to “2&2” or four classes a year. This isn’t true everywhere, but at a lot of institutions, professors are teaching only 70% of the time and half the classes that they taught in the 1960’s!

This, not the summer breaks, is the issue — and the pressure for the months-long summer breaks is coming from the tourist industry. The students are needed not to plant the crops but to serve as cheap labor for the hospitality industry. At least in New England, very powerful political interests make it impossible to have an academic year that extends beyond Memorial Day, or which starts before Labor Day — hence the occasional 12-week fall semester.

And when you look at expenses, building space is cheap when compared to faculty time. The loss of faculty teaching time is the real problem…