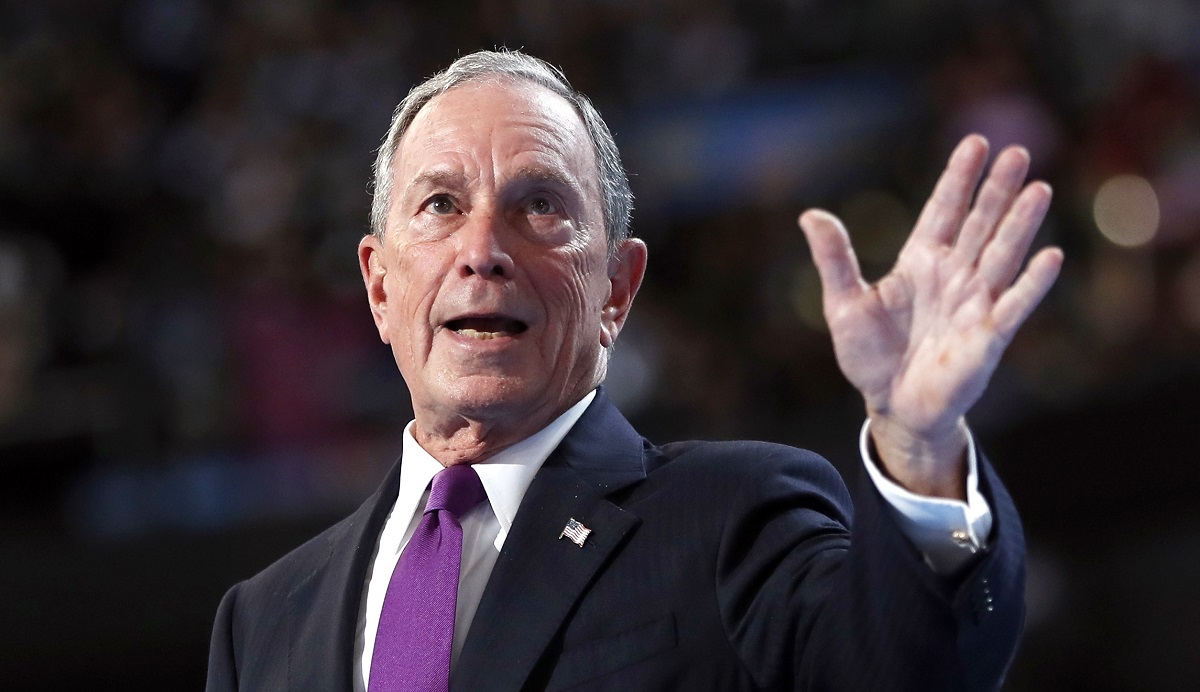

Former New York City Mayor, Michael Bloomberg, made headlines by arguing in a political column that political rage and increasingly polarized discourse are endangering the nation. He said Americans are too unwilling to engage with people whose ideas are different from their own. He added that Americans used to move forward productively after elections regardless of which side won but now seem paralyzed by absolute schism and intolerance.

To put it simply, Bloomberg wrote, “healthy democracy is about living with disagreement, not eliminating it.” He pointed to college campuses as a prime example of the problem, citing Steven Gerrard, a professor at Williams College in Massachusetts. Students declared Gerrard, “an enemy of the people” after he suggested that Williams join other schools in signing onto the Chicago statement, published by the Committee of Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago. The statement calls for free speech to be central to college and university culture.

The anti-Gerrard statement came in a letter in which students called free speech a term that has been “co-opted by right-wing and liberal parties as a discursive cover for racism, xenophobia, sexism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism and classism.”

Bloomberg pointed out that fewer than 70 of America’s 4,000 colleges and universities have endorsed or adopted the Chicago statement.

implicitly labeled as “dangerous”

Sadly, this reprehensible tactic has become quite common after Virginia Tech.

I can’t help but wonder if Berea College has a “Behavioral Intervention Team” as the speed at which this all happened seems to indicate that it was all pro forma — that the top administration (i.e. the BIT) had already reached the decision.

I don’t know about Kentucky, but in Massachusetts I’ve seen male veterans considered “dangerous” because they’ve qualified with a M-16 and often other weapons (e.g sidearm). Knowing how to use a gun somehow inherently means likely to shoot everyone on campus… And somehow this prejudice doesn’t extend to female vets….

As an aside, if you were active duty before 1975, you are considered a “Vietnam Era Vet” and Berea College (which I presume receives Federal funding) well may have violated your protected status under that, it applies to employment. Make sure your lawyer knows this.

implicitly labeled as “dangerous,”

This is perhaps the most obnoxious of tactics, and one which is annoyingly common.

I think the most interesting thing is that it was written by Michael Bloomberg and not Ted Cruz — it shows just how far down the path of the French Revolution we have gone.

I have to disagree with Bloomberg on one point: this isn’t Right versus Left — it’s Left versus Further Left, just like during the French Revolution. And it is folks continually ever further to the Left wielding the guillotines, just like back then. The activists at Williams make no distinction between “right-wing and liberal parties” which shows how far to the Left they actually are.

In fairness, its only been people’s careers and reputations being destroyed (at least so far) but this has been going on for forty years now, while the French Revolution lasted only ten, with the actual Reign of Terror lasting only 13 months. How much longer will we tolerate the carnage of our own Reign of Terror?!?

Is Berea College becoming a “boutique of the banal”?

Dave Porter – Berea College, professor in exile

In 2010, a federal appellate court (that included former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor) asserted the role of free speech in higher education: “Without the right to stand against society’s most strongly-held convictions, the marketplace of ideas would decline into a boutique of the banal… The right to provoke, offend, and shock lies at the core of the First Amendment. This is particularly so on college campuses… We have therefore said that the desire to maintain a sedate academic environment does not justify limitations on a teacher’s freedom to express himself on political issues in vigorous, argumentative, unmeasured, and even distinctly unpleasant terms.” Educational institutions exist to educate and inspire students through the discovery and dissemination of knowledge. Freedom of speech and academic freedom are indispensable components of this mission; they are higher education’s effervescence. In 2010, Berea College was an institution committed to free speech and quality education.

I was born in Berea. My father was a student here at Berea College. He graduated in 1952, the first in his family to earn a college degree. He then earned his law degree at the University of Kentucky. He became an FBI agent; we moved six times before I entered high school just east of Los Angeles. After high school, I attended the Air Force Academy, graduating in 1971, then earned a master’s degree from UCLA in 1972, and completed Undergraduate Helicopter Training in 1973. I served as an Air Force rescue helicopter pilot, and earned qualifications as an aircraft maintenance officer, equal opportunity & treatment officer, and race relations instructor. I became an instructor at the Air Force Academy in 1979 but returned to flying duties two years later. In 1983, I entered Oxford University, and 2 ½ years later, graduated with a doctorate in experimental cognitive psychology. I returned to the Air Force Academy and rose through the academic and military ranks to become the Permanent Professor and Head of the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership in 1996. Our department was diverse and dynamic and our major was one of the most popular at the Academy. Although my relatively liberal religious and political views were not shared nor always appreciated by my military colleagues, I did not doubt that they would be tolerated or that I would have the freedom to teach and conduct research in the behavioral sciences while at the Air Force Academy.

In 2001, I retired from the Air Force and returned to Berea College as the academic vice president (AVP) and provost. When I arrived, the graduation rate for the college had gone from bad to worse, reaching a nadir of 45%. I helped a dedicated and talented administrative staff identify impediments and implement key initiatives. Two years later, for only the fourth time in the college’s history, over 60% of the cohort of students who matriculated six years earlier graduated. The academic staff worked hard to change the system to sustain this exceptional performance; the 6-year graduation rate has remained above 60% for the last 16 years. I coordinated our efforts to prepare for the dreaded SACS Accreditation visit (Berea had incurred nearly 50 negative recommendations during their 1995 visit). We passed our 2005 inspection easily with only a single adverse finding. Also, during my time as AVP, every faculty member recommended for tenure by his/her department was endorsed by the Faculty Status Committee. All this was accomplished without significant increases in the cost of education. Nonetheless, I welcomed the completion of my administrative duties and return to the classroom once the accreditation visit was complete.

Being in the classroom and working directly with students is much more satisfying than administration. I was selected as the college’s Outstanding Academic Adviser in 2007, and in 2008, as the college’s Outstanding Labor Supervisor. Student evaluations indicated that my courses were engaging, inclusive, innovative, and integrative. Questioning Authority; Skepticism as an Antidote for Oppression and An Introduction to the Behavioral Sciences: Anthropology, Psychology, and Sociology were two courses that achieved great success as well as some notoriety. My post-tenure review showed that students rated my teaching in the top 10% of the faculty – more recently, these ratings have been in the top 5%. I inherited our senior research capstone course, and, over the next decade, nearly 30 of my research protégés earned awards for their research at state and regional undergraduate competitions. And yet, a panel of my peers has decided I am too incompetent to continue at the college. Let me explain.

Over the last two years, I’ve observed Berea College slipping down a slope of political correctness and the erosion of its former vitality as an institution dedicated to ideals of inclusivity, diversity, freedom, and providing a top-quality liberal arts education. It began with an ambush of my department chair. A grievance against him alleging discrimination in hiring & promotion, retaliation, and creating a hostile workplace environment led to his removal as chair and banishment to the basement of our building – the only other denizens in this subterranean abode being the 70 some snakes in the college herpetarium. After a cursory Title IX investigation, most of the charges against him were dropped. However, my colleague was found to have created “a hostile work environment”. In the end, there were three violations over a two-year period: telling an inappropriate joke prior to a department meeting, attempting to engage junior colleagues in conversations about the backlash to Chrissy Hynde’s interview on NPR about her rape, and using the phrase “militant lesbianism” during a heated discussion of a student disciplinary problem in one of his classes. He was found to be guilty of being “impulsive”, “aggressively oblivious”, and “erratic”. As it turns out, these are all symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). He received this official medical diagnosis after a subsequent clinical assessment. Unfortunately, this diagnosis arrived too late to influence the administrative decisions to remove him as department chair and banished him to the basement.

These events did not occur in isolation. Over the last decade, evidence of a steady decline has become increasingly apparent. For example, the most recent Institutional Research Report tracks retention rate trends for a variety of demographic subgroups by comparing performance for the current academic cohort (those who entered the college in 2016 in this case) to the three previous cohorts. This report shows declines in the following groups: White Males (-16%); Students from Distressed Appalachian Counties (-14%); Students from Kentucky (-10%); Students from the Top Quintile of the high school graduating class (-8%); and First-Generation College Students (-7%). Many of these students reflect demographic categories that have been central to the college’s traditional mission of providing high quality education for students of great potential but limited financial resources in the Appalachian region. Similarly concerning data can be found in the most recently published 4-year graduation rates. These rates are the lowest they have been in the last decade for certain groups, including: Males (33.1%) in general and African American Males (20.0%) in particular.

My attempts to address my concerns about these negative trends and the lack of due processes in the Title IX case were systematically ignored or rebuffed. While many faculty members and administrators acknowledged the problems, the president and dean were unwilling to address my concerns directly. As a psychologist and researcher with over 50 published studies and several book chapters, I engaged my Industrial/Organizational Psychology classes in developing a survey of community attitudes about academic freedom, freedom of speech, and the perception of hostile work environments. The heart of this survey was a set of scenarios. Respondents were asked to read the scenarios and decide whether each situation reflected a “hostile work environment” then whether the action taken in the scenario would be protected by academic freedom. The use of such scenarios (i.e., situational judgement tasks) is common in both cognitive and I/O psychology. Many of these scenarios related to recent events on campus.

Scientists solve problems by gathering evidence; the main problems I saw with our Title IX Program was that the politically-correct attitudes of those in charge set the agenda with scant attention to evidence of effectiveness or community consequences. Before publication, I shared drafts of the survey with many other faculty members and received feedback from six of them including my academic division chair, the chair of the Institutional Review Board and Director of Academic Assessment, and faculty members with relevant experimental and applied experience. None of them mentioned ethical concerns, potential harm to subjects, or “confidentiality” issues. There was concern about the controversy the survey might elicit by raising issues the administration wanted to conceal. The survey was launched on a Monday in February; by Tuesday, the campus was in an uproar. One of the original grievants against my department chair claimed on social media that she was the subject of “all” the scenarios, and this was an attempt to “retaliate” against and “silence” her and her colleagues. The charge of “false survey” spread like a claim of “false news” at a Trump tea party. The dean publicly requested I withdraw the survey and apologize to the campus community. However, in a subsequent phone call, he promised to forward some of the grievances to me and provide a list of the most problematic scenarios for me to reconsider. However, he never provided this information.

Contrary to the assertions of several concerned “social scientists,” data from the survey’s 120 valid respondents yielded compelling results: Demographic characteristics influence beliefs which, in turn, predict much of the variance in respondents’ perception of the presence of hostile work environments and subsequently, their judgments about academic freedom protection. A large majority of the respondents indicated that they did not express opinions openly because they feared retaliation for expressing views deemed offensive or politically incorrect. Contrary to respondents’ explicit claims of support for both protection from hostile environments and academic freedom, the survey scenarios showed that those who perceived situations as being “hostile” were unlikely to acknowledge academic freedom protection. The results also revealed that most of our current Title IX “training” programs do little to affect attitudes or perceptions. Nearly three-quarters of the respondents viewed the survey itself as being protected by academic freedom. The administration’s interest in suppressing these results was clear and their willingness to pursue this goal zealously was soon manifest.

On Thursday, three days after the survey was posted, I and my academic division chair were summoned to the dean’s office and advised that charges of incompetence were to be brought against me. Stunned, I asked if we could discuss the matter. The dean’s curt reply was that the time for discussion had ended three days earlier. This violated the process prescribed in our Faculty Manual. He later acknowledged that he was just too emotional at the time to discuss the matter with me. Shortly thereafter, he presented the case against me to the Faculty Status Committee. Most of the committee members concurred with the dean that I should be terminated; they simply accepted his assertion that the survey was a weapon of malicious retaliation against my innocent and unsuspecting colleagues. I was not allowed to defend myself before the committee and, to the best of my knowledge, there was no investigation of the case he brought against me. The specification of charges contained factual errors and omitted significant exculpatory evidence concerning the use of situational judgment inventories in I/O research, the prior review of the survey by other tenured faculty members, and the extensive assistance provided by the Chair of the Institutional Review Board & Director of Academic Assessment in preparing the survey for posting. Shortly thereafter, I was summarily suspended from the college; my classes were re-assigned; I was prohibited from communicating with students, implicitly labeled as “dangerous,” banished from campus, and through a distorted post hoc, in absentia application of published IRB procedures, prohibited from using or sharing data from the survey. In my 34 years of military service, I had never been treated so unfairly.

My attempts to discuss the situation or understand the nature of my alleged transgressions detailed in the charges against me were consistently rejected by the administration. Efforts by the Student Government Association to award me their annual Student Service Award were stymied by a message circulated by a junior faculty member making defamatory claims about my former department chair, me, and my research. Just as the spring semester ended, a small group of my colleagues were persuaded by the dean that “my personal conduct had demonstrably interfered with my professional responsibilities,” that my tenure should end, and I should be dismissed from the college. The college’s explicit promises to protect faculty teaching, research, and freedom of speech were ignored. The testimony of several concerned female social scientists was given more weight than the expert testimony of a leading national expert in I/O Psychology and two Berea College graduates recently completing doctorate programs in Quantitative Psychology. Raw testimony presented only in written form by the aggrieved was afforded great weight by the committee despite not having been cross examined. At the dean’s insistence, and over my objections and AAUP Guidelines, the panel adopted the “preponderance of the evidence” standard and provided me with only a single day to present my defense rather than the two days I requested. The dean, who directly supervised all members of faculty panel (as well as all faculty witnesses appearing before it), persuaded them to recommend my ouster, and the president, who had already implied in his messages to the campus that I was a danger to others, agreed with them. I was given two weeks to resign or be fired. After a subsequent review of my case, the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees supported the president’s decision and my employment at Berea College ended on September 30th, 2018.

I am grateful for having had the opportunity to contribute to Berea College and its distinctive mission and wonderful students. The Faculty Appeals Committee found that the survey I had prepared with my students was not an act of retaliation and that it was, in fact, an academic endeavor, with an academic purpose related to the content of the course I was teaching. However, I was also found to have breached my professional responsibility to maintain confidentiality. However, “confidentiality” is not defined in our Faculty Manual and is not assured or required by the sections on Title IX standards or proceedings. This was a case of post hoc persecution, plain and simple.

I believe my “incompetence” and alleged violation of my “professional responsibilities” were pretexts. The administration’s final offer of an alternative separation settlement revealed the real issues in this case. The college offered me a year’s severance pay (something recommended for all dismissed faculty members by the AAUP guidelines) and the opportunity to earn retiree status after a year. All the administration asked of me was that I sign perpetual non-disclosure, non-disparagement, and hold-harmless agreements, withhold publication of my study for a year, and stay away from campus for a year. They later amended this to include an agreement that I never enter a “classroom building” without written permission from the college provost. They simply wanted me to shut up and go away; they wanted a sedate campus, one that creates a “safe space” veneer by squelching dissent, avoiding controversy, and the authentic disagreements characteristic of a liberal arts education and its “marketplace of ideas”. I did not accept their terms. I intend to seek justice, not only for myself but for all members of the college community, through an external judicial appeal. This process is now underway.

“Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything” – Colin Kaepernik. Or in the words of Winston Churchill, “Success is not final; failure is not fatal; it is the courage to continue, that counts.” I will continue…