The United States Supreme Court agreed on Monday to hear cases against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina challenging the use of racial preferences in college admissions. The cases could lead to the overturning of the Court’s 1978 and 2003 holdings in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke and Grutter v. Bollinger that achieving “student body diversity” is a “compelling interest” justifying the otherwise illegal use of race in the selection process.

The current lawsuits were brought in 2014 by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), an advocacy group representing Asian-American and other students rejected by top colleges that employ racial preferences. The challengers alleged that Harvard’s admissions policies discriminate against Asian-American applicants, and that UNC discriminates against both Asian-Americans and whites, in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits racial discrimination by recipients of federal funds. In addition, the complaint against UNC, a public university, charged it with violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

A federal district court in Massachusetts ruled for Harvard in 2019, and its decision was upheld by the First Circuit Court of Appeals in 2020. Meanwhile, a North Carolina district court ruled for UNC last fall, but the Supreme Court took the unusual step of allowing a direct appeal from that court in order to hear the two cases together.

The Harvard case, in particular, gets to the heart of the problem with the current use of racial preferences, and with the problems that have underlaid Bakke and Grutter from the beginning. That is because it brings into stark relief that, whatever the merits of racial preferences may have been in the largely biracial era when Bakke was decided, in our current multiracial era they now come largely at the expense of Asian-Americans, another racial minority historically victimized by discrimination. Further, Bakke and Grutter were founded on a lie, since they held out Harvard’s “holistic” admissions system as a model of the acceptable pursuit of “diversity,” when in fact that system was put in place to exclude Jews who were stereotyped in much the same way as Asians are today, and now cloaks similar invidious prejudice against Asians.

[Related: “Anti-Asian Discrimination at the Heart of the Progressive Education Agenda”]

Briefs I filed for the National Association of Scholars (the parent organization of Minding the Campus) urging the Court to hear the Harvard and UNC cases stressed these points, and also argued, drawing on NAS research, that in practice, race-based admission has led not to diversity but to “neo-segregation” on campus, featuring separate graduations, separate dorms, and even separate classes. We noted that:

• While, in his controlling opinion in Bakke that was later adopted by the Court in Grutter, Justice Lewis Powell spoke of diversity as fostering a cross-racial “atmosphere of speculation, experiment and creation,” in fact, by placing many black students in more competitive academic environments than they were prepared for, racial preferences actually lead them to retreat into homogeneous segregated enclaves.

• Studies at Harvard and other elite colleges have found that up to 80 percent of slots awarded to African-American and Hispanic students under preferential admissions come from Asian-Americans rather than whites. Harvard’s own Office of Institutional Research found that removing racial preferences for blacks and Latinos would increase Asian enrollment by 45%, but white enrollment by only 15%. This suggests that in deciding who must give up their seats in the name of racial diversity, admissions officers may ironically fall back on the subconscious racial stereotypes of Asians as “textureless grinds.” Thus race-conscious admission, once seen as a tool for combatting racial bias, now provokes it.

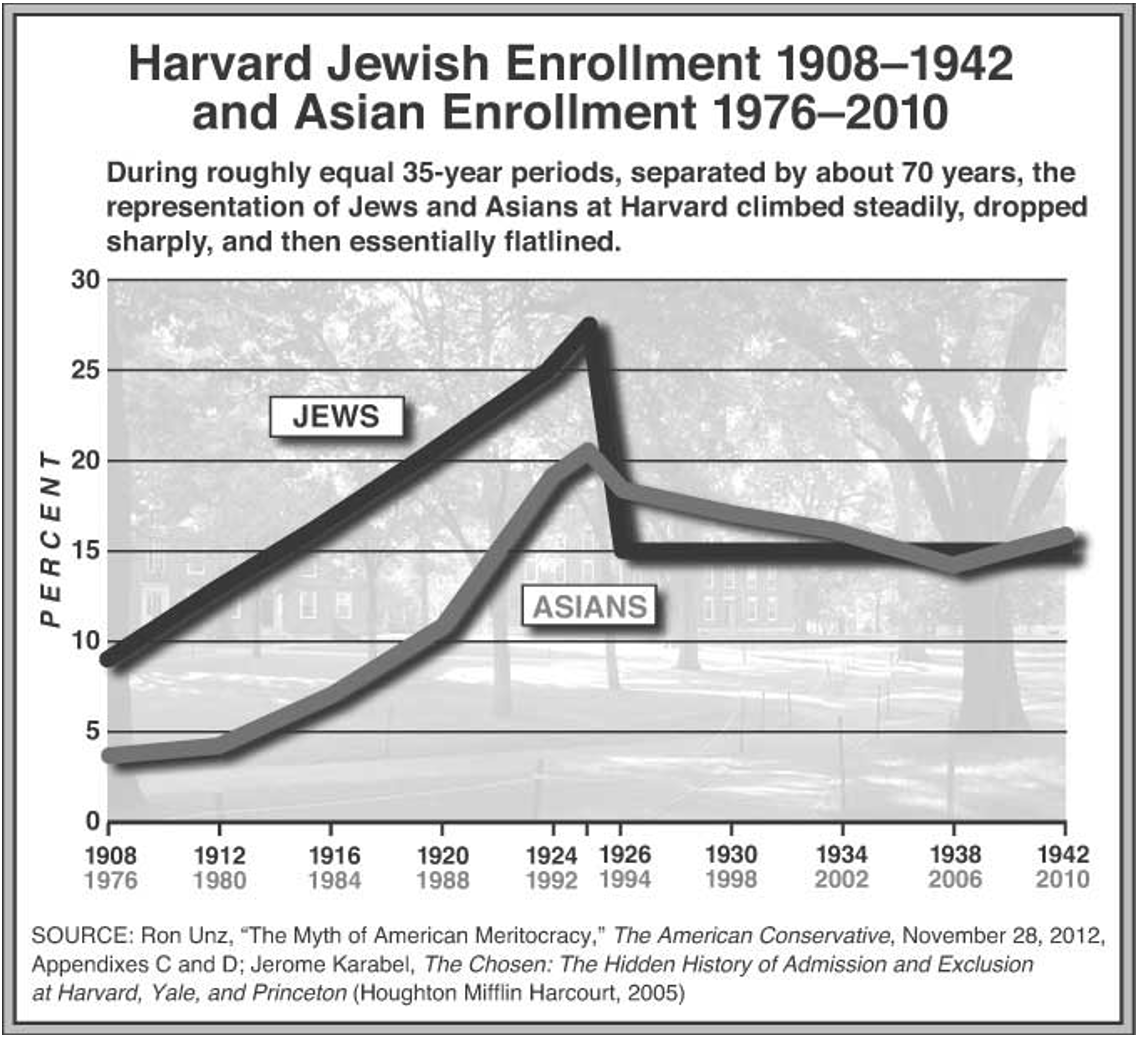

• “Holistic” admissions criteria stressing “character” rather than academic achievement were introduced at Harvard in the 1920’s in a blatant and successful effort to place an informal quota on Jews, whose numbers had grown to over 25% of the student body under the old merit-based standards. The uncanny parallel between Jewish enrollment figures at Harvard in the early 20th century and Asian enrollment over the last forty or so years—starkly illustrated in the chart below—suggests that Harvard now deems another upstart, achievement-oriented minority that has been too successful under objective standards to be deficient in subjective measures of “character.” Evidence in the case that Harvard admissions officials have consistently given Asian applicants the lowest “personal” ratings supports this conclusion.

[Related: “At Foothill College, Equity Collides with Education”]

In her majority opinion for the Court upholding racial preferences in Grutter in 2003, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor noted that it had “been 25 years since Justice Powell first approved the use of race to further an interest in student body diversity” in Bakke, and added that “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.” But, as discussed above, in the multiracial America of 2022, preferences now largely victimize another racial minority group, while contributing to neo-segregation rather than diversity on campus. Racial preferences, the flagship policy of the multiculturalists, have foundered on multiculturalism itself. While the sell-by date set by Justice O’Connor 19 years ago may still be six years off, it’s time to retire them now.

Ummmm…..Bakke won….

The claim that wonderful and glorious benefits arise when the student body is racially diverse is insulting and, like many claims from the left, offered without a shred of evidence. Admitting marginally qualified students who just happen to have the right skin color–i.e., not white–benefits only the diversity, equity and inclusion bureaucracy on campus.

https://www.carolinajournal.com/opinion-article/the-tragic-life-and-death-of-a-poster-boy/

https://www.jeffjacoby.com/10931/affirmative-action-can-be-fatal

Perhaps this time the Court will actually employ “strict scrutiny” rather than lazily deferring to the presumed expertise of the university officials.

The Civil Rights Act prohibits racial discrimination by educational entities that receive federal funds. It doesn’t say “But discrimination is all right if the officials think it is somehow a good thing.” The claim that diversity creates wondrous educational benefits is hollow, but even if it weren’t, that would hardly justify ignoring the nondiscrimination language of the law.