Statesmanship has fallen on hard times. Modern social science cannot make sense of this once-popular category of classical political philosophy, and the virtues commonly associated with the statesman today are equated with toxic masculinity or worse.

Fortunately, in his new book, “The Statesman as Thinker: Portraits of Greatness, Courage, and Moderation,” (Encounter Books) professor emeritus at Assumption University Daniel J. Mahoney revives the study of statesmanship, profiling eight pivotal leaders in the history of Western civilization. Using the template Plutarch provided in his “Lives,” Mahoney highlights individuals who utilized a rare combination of cardinal virtues and philosophic insight to save their respective nations from destruction.

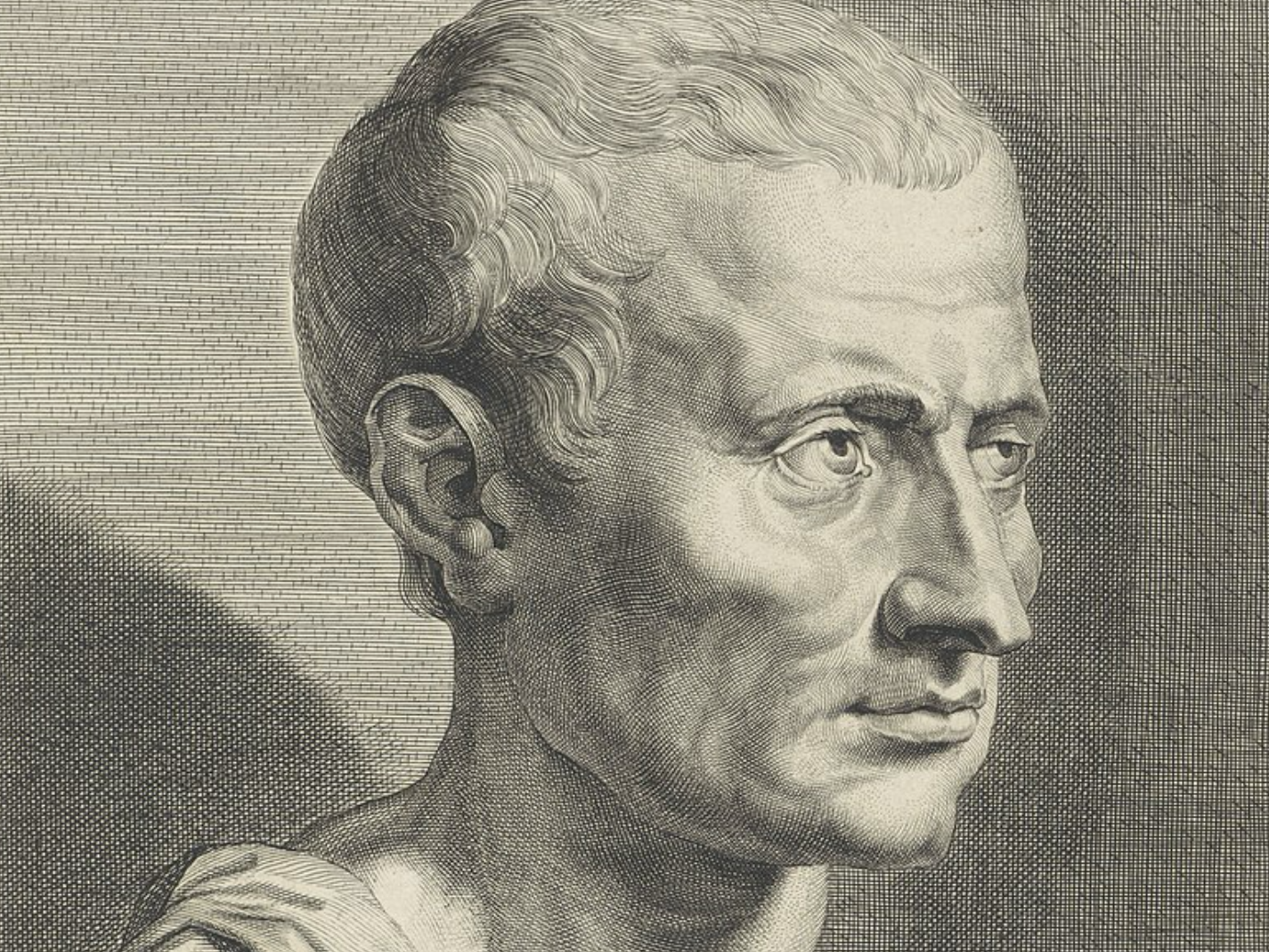

Mahoney’s chapters examine the Roman orator and senator, Cicero; the well-known member of Parliament and conservative political thinker, Edmund Burke; the friendly French critic of America, Alexis de Tocqueville; the greatest American president, Abraham Lincoln; the prime minister who led Great Britain against Hitler, Winston Churchill; the great French World War II general and later president, Charles de Gaulle; and the anti-communist dissident and Czech president, Václav Havel. Though some might be surprised at the absence of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan or Margaret Thatcher, Mahoney chose these particular statesmen because they were exceptional thinkers in addition to possessing the full complement of moral and civic virtues.

Each portrait is built around a discussion of major works by and about these statesmen, including classics such as Aristotle’s “Constitution of Athens” and Cicero’s “On Duties” as well as important recent books such as Robert Faulkner’s “The Case for Greatness” and Gregory Collins’s “Commerce and Manners in Edmund Burke’s Political Economy.” At the end of each chapter, Mahoney includes a short bibliography featuring helpful observations and a listing of the books discussed, complete with page numbers of key sections.

Mahoney argues that in their fight against “rapacious and destructive regimes and ideologies” such as Caesarian despotism, Jacobinism, Naziism and Soviet communism, each statesman possessed virtues such as magnanimity, courage, moderation and restraint, as well as Christian virtues such as charity and humility. By moderation, Mahoney does not mean a mealy-mouthed centrism but instead an understanding of their own limitations and what was possible given the circumstances they faced.

[Related: “‘Heroes of Liberty’ Highlights Key Statesmen, Thinkers”]

Statesmen of this caliber put aside private gain and self-aggrandizement, Mahoney writes, to exercise “commanding practical reason” (in the words of French political theorist Pierre Manent) to achieve the common good of the nation. As Robert Faulkner has argued, they harkened to the well-formed judgment of “decent people [who] have an eye in particular circumstances for the fitting or correct thing to do.” Rejecting abstractions untethered to reality, they stood for prudence over an ideological anti-politics – which, in the 20th century in particular, has left nothing but carnage in its wake.

In light of the U.S.’s troubles in the Middle East and the ongoing Russian–Ukrainian War, understanding the role of prudence in foreign policy is vital. As Mahoney argues, “Not every moment is a repetition of Munich 1938. Sometimes good sense and prudential reasoning demand restraint, especially if one is dealing with a sane regime informed by civilized values.” A prudential statecraft should be guided by considerations of how to secure national interests given present realities rather than utopian claims that have too often resulted in disaster, especially in recent times.

What’s needed today, Mahoney says, is a conception of statesmanship supplied by Aristotle and Cicero in which political action is “informed by political philosophy” that’s good both “for the soul and good for the city.” He continues: “This model of reflective statesmanship, judiciously melding thought and action, greatness and moderation, and humble deference to the divine and moral law, rivals contemplative philosophy as an enduring peak of human excellence.” Mahoney, however, breaks with Aristotle’s view of magnanimity, preferring Cicero’s “improved account,” because it includes a “concern for justice and for one’s fellow men and citizens,” along with the maintainance of a “free and dignified political life” rather than an austere self-sufficiency.

In contrast to modern political elites who regularly show their contempt for average Americans, these statesmen never looked down on common people. Mahoney notes that despite Churchill’s aristocratic upbringing, he was “no crude snob”; instead, he had a deep “respect for the dignity of ordinary people, in their simple ‘cottage homes.’” And leaders like de Gaulle understood that the “truly great man was a ‘born protector’ and not a tyrant and a destroyer of bodies and souls.” With a greatness of soul that included genuine patriotism and a love of country, these statesmen worked to defend “the inheritance that is civilization itself.”

Though each stateman possessed the complete range of moral and intellectual, martial and civic virtues, he also recognized what de Gaulle characterized as the role of “contingency, chance, and choice in the unfolding of human affairs.” Events are the means by which statesmen harness their private virtues in service to great causes – as the Civil War was for Lincoln and the Cold War for Havel.

[Related: “Can We ‘Long March’ Back through the Institutions?”]

In perhaps the book’s best chapter, Mahoney highlights Edmund Burke, the first statesman to “discern the true nature of ideological despotism” in the trappings of the French Revolution. Mahoney, of course, writes against the backdrop of an American cultural zeitgeist infused with a quasi-religious Jacobinism that seems intent on eliminating all traces of the past. Like today’s cultural revolutionaries, French radicals of the late 18th century gave primacy to the untutored will and attempted to subvert any connection to their country’s history. Ultimately, they dethroned God and placed “man with his free will . . . on the vacant seat,” as the Dutch statesman and theologian Abraham Kuyper once said.

Mahoney describes Burke as “a friend of liberty, a caretaker of a tradition of liberty that required prudent statesmanship and, at times, a tough-minded conservative reform.” In standing against the revolutionaries – whom he accurately called a “mischievous and ignoble oligarchy” – Burke appealed to a Christian prudence grounded in nature that was aimed at preserving civilization for posterity. As Burke wrote, “This is the true touchstone of all theories which regard man and the affairs of men – does it suit his nature in general – does it suit his nature as modified by his habits?”

While Burke was a great friend of traditionalists, Mahoney shows that he also kept a place in his political thought for human reason (distinct from rationalism) and an understanding of rights and natural law, though an abridged version as Yuval Levin has shown. And though Burke was an admirer of the market economy, Mahoney contends that he was nevertheless a “critic of the effort to reduce the whole of human life to economic criteria.” Burke was no two-dimensional figure, with nothing to teach Americans about political life.

Another virtue of the book is Mahoney’s avoidance of hagiography while showing that human greatness remains possible in a fallen world. He candidly points out Tocqueville’s infidelity, Churchill’s blunders while in public office – which include continuing the military operation in Gallipoli after March 1915, the disastrous Norwegian campaign of 1940, and his decision to remain prime minister after his 1953 stroke – and Havel’s affairs and eccentricities. Despite such failures, statesmen of this elevated rank are always needed in human affairs.

Mahoney concludes by calling all Americans – and citizens of the West more broadly – to “open ourselves to excellence in all of its forms” and reaffirm the “spirit of gratitude for what has been passed on by our forebearers as a precious gift.” The outstanding examples of human greatness that Mahoney profiles should fire the imaginations of future statesmen looking to preserve our civilization.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by RealClearBooks&Culture on July 13, 2022 and is crossposted here with permission.