In Part One of this essay, I analyzed the ways in which two contrasting lenses—the liberal lens and the critical lens—affect postsecondary administrative practices and curricular development. I also asked whether there is any defense of the critical lens in education. To read my assessment of those two subjects and to get more background on the lenses, click here. Now, I turn to two other arenas in which these paradigms play out: individual identity and social relations.

Individual Identity

The student’s sense of self, of belonging to the college community—the individual’s identity—is tied to “success.” Success can be academic, athletic, or relational. Administrators with a liberal lens will generally truncate the metric into one of performance and merit; administrators with a critical lens postulate a group-affiliated identity (race, gender, religion) mediating the metric of performance and merit.

Students are often oblivious to how college administrators seek to shape such success. Students are immersed in an educational process, learning about the world and themselves. Here, “success” is more than the external metric (the grade); it is also the internal metric of self-concept. But the educational institution has an interest here as well—whether that is building an identity based on character or based on an intersectional composite.

Generic discussions of identity can be placed in various contexts—the huckster, the inmate, the sailor, the Rosie-the-Riveter—all of which can and have become central to narratives in books, movies, and TV dramas. Religious identity has historically been formed through education in monasteries, convents, madrasas, and yeshivas; secular identity may focus on nationalism and political identity, informing education with an intensive ideological framework from Turkish Kemalism to Russian and Chinese nationalism, as well as the more superficial approach of a daily Pledge of Allegiance in the United States.

Today, if you review any college catalog, discussions of identity are frequently found in ethnic studies, cultural anthropology, sociology, communication, literature, and the like. However, even science classes, as noted in Part One, are incorporating identity, primarily from the perspective of race, ethnicity, and gender.

In my classroom, I discuss the student’s self-concept with the following exercise. I ask the students to list several identities. Their lists vary, having identities from brother or sister, father or mother, son or daughter, student, Christian, veteran, Chicano, American, and so on. I ask them to rank their identities from the least to the most important. I then begin a process of elimination, going around the room asking what identity they have for number four, asking them to discard number four and turning to number three. When I reach their most important identity, I ask them to discard their last identity. “Now, who are you?” The look of puzzlement ends with some saying “nothing” and others saying “human.” That is my teachable moment. From a mystic’s perspective, “nothing” and “human” merge into the mindful practice of focused breathing. It also takes them to the place that the mystic Rumi rhapsodized in his meditation on breathing. Granted, it is difficult to maintain that selfless human moment—the world around us pulls us back into our accustomed stereotypes.

[Related: “Is There a Defense of the Critical Classroom? Part One: Administration and Curriculum”]

This exercise demands no central core identity other than being human; it is organized around students’ individuality; it plays into the various roles they occupy in society as well as their personal life experiences. The exercise is also a prelude to the textbook’s readings on the subjects of race and ethnicity, sex and gender, marriage, kinship, vocation, and the like.

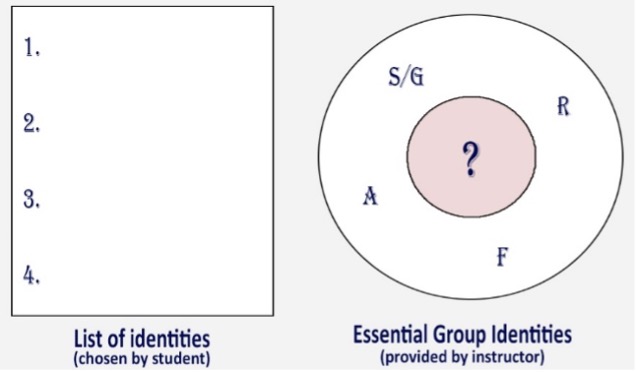

Contrast my approach (see Figure 2 List of Identities) with one that fills the core identity with a race or gender (see Figure 2 Essential Group Identities). The latter preempts the self-selected individuality with a claimed essential authenticity; such authenticity generally emerges from a marginalized and oppressed community, sometimes visualized as an intersectional wheel. The stereotypical white, male identity is generally seen as an oppressor.

Figure 2. Two approaches to the ‘Who am I?’ question in class discussion topics such as race and ethnicity, sex and gender, magic and religious belief, and so on.

Answering the ‘Who am I?’ question directly informs curriculum and pedagogy. Pedagogy that sees identity through a critical lens has resulted in constitutionally grounded lawsuits.

Joshua Dunn’s article in The Critical Classroom highlights this problem. William Clark, a high school senior, was required to take a class in the sociology of change at Democracy Prep in Las Vegas. While he called himself white, having blondish hair and green eyes, he was biracial, with a black mother and a white father. He refused to state he was privileged because he appeared white. Other teachings that he would have acceded to included, “people of color cannot be racist.” He would have failed the class, except that he filed a lawsuit in federal court. The judge advised that Clark’s lawsuit would likely succeed following a strict scrutiny test under a variety of antidiscrimination statues and cases. The school decided to relent and allow Clark to graduate.

Other violations are emerging both from school district and state curricula mandates. Students have demanded that their teachers and peers comply with the new pronoun correctness: a Loudoun County teacher’s refusal to call a transgender student by a preferred pronoun was protected as his constitutional right to free speech in a Virginia court. Likewise, a college professor won a similar action against a transgendered student’s preferred pronouns based on his First Amendment rights, with the court noting in a unanimous decision, “The First Amendment interests are especially strong here because [the professor’s] speech also relates to his core religious and philosophical beliefs.” These lawsuits arise in the context of a critical lens—sometimes embedded in race, sometimes gender.

As I have argued elsewhere, individual protections against discrimination—which are characterized as a “shield approach”—are sometimes transformed into programs that would change society through a “sword approach.” The sword approach can result in constitutional overreach. Such overreach has thus far been fended off under First Amendment guarantees against the imposition of ideological belief. The perceived need to change society often rests on the imperfect metric of perceived rather than actual discrimination. There is a further, more troubling, problem with relying on a critical lens to shape behavior and belief in the classroom—that, according to Ian Rowe in The Critical Classroom, schools “are teaching ideas that weaken student agency, pit children against one another, reduce human behavior to immutable characteristics such as skin color . . . .” To be sure, biology and culture have shaped sex and gender differently than they have race and ethnicity; yet, given the critical lens’ intersectionality framework, Rowe’s critique of reducing race to skin color could equally apply to confounding the sex–gender identity in ways not fully appreciated.

[Related: “A Wicked Inquiry into the National Conversation on Race: Why You Should Read My Book”]

Social Relations

The tension between a liberal and a critical lens plays out in social relations as well. Some argue that people of color should be segregated from white individuals in order to heal. Are racial equity groups justifiable for therapeutic reasons? What would a therapeutic safe space look like?

The rationale for “race-based affinity groups” is straightforward when applying a critical lens. Here are five reasons in support of them courtesy of the organization Unbound:

1. People of color need spaces to grieve, lament, mourn, and share their emotions in community away from white people.

2. White people created white supremacy, so white people need to do the work to dismantle it.

3. White people talking about white supremacy can re-traumatize people of color.

4. People of color are exhausted from teaching white people about racism and white supremacy.

5. Affinity groups help us to live into the feeling [Unbound’s phrase] of being uncomfortable.

“Why are we separated? I feel uncomfortable with this. Seems like we should be doing this work together.” “Why are we segregating?” These are often questions asked when affinity groups based on race are used to do the work of dismantling racism. . . . Living into this uncomfortableness is a stage in dismantling racism and white supremacy … so white people must get used to it.

It is strange how the history of the United States began with slavery, continued to discriminate after the Civil War until new institutions were built with civil rights laws and court decisions, and, now, maintains the logic of discrimination in contemporary thinking. Thus far, the current legal framework makes applying this “logic” unlawful, but we are not without attempts to institute it. This is where accurate historical analyses are important, such as those found in The Critical Classroom. However, speaking as an anthropologist, we still ought to reach beyond the legal framework to understand how the therapeutic apparatus of a safe space unfolds. In effect, we should comprehend the psychological reality that empowers those who view reality with a critical lens.

The Navigating Intersectional Identities Panel discussion (edited) provides us with insight into such a safe space. Arguably, this is the operative language that would be central to a race-based (or gender-based, or race-gendered) affinity group. Here, the group is defined with several intersectional identities: QTBIPOC (queer, trans, black, indigenous, persons of color) within the context of those working in the design industry.

I want people to just be their true selves, no matter what, you know. And I know it’s a lot to ask for, but yeah, because I feel like all of us are still dealing with all these friction points . . .

I can never use my first or last name. I always have to use Robin, Tom something, you know? And that’s, it’s dehumanizing and it’s something so small, you know . . . I never want to say I’m from Hawaii originally.

Cause A I say it with the accent and B they’re like, Hey, do you like to surf? Do you like . . . apples? Do you like that pizza? Oh my God. How do you not punch somebody in the face, especially when you’re having the worst day in your life and somebody just approaches you with these inconsiderate ignorant kind of views and you know, and that heat of the moment you’re like, should I just walk or should I school this person you now?

Will I look proper and will, how will they see me? I don’t give a shit because I’m bringing all of my authorized parts. Intersectionality is all about parts. And when you de-authorize a part and not authorize or de-authorize some of it, but don’t authorize all of it.

You are not living authentically, not your whole self. It’s about my authentic self, all of those parts, how I exercise them, that’s up to me, but I’m authorizing them all when I show up . . .

You know, they can’t force people to learn and unlearn certain things if they’re not willing to begin to do the work. And so that, yeah, I also have a lot of friends who have taken up roles in the DEI space, and it’s just so hard because one you’re the first to get fired if anything goes wrong. . . You aren’t just the DEI person who runs some of the activities you become, the HR person, you become the PR person, you become executive leadership coach. You become this point of intersection that needs to exist for everyone.

So it’s just, again, it goes back to us. BIPOC folks shepherding all of these critical conversations that we’ve already been doing this work and it’s time that other people have to sign.

How many times have you had the conversation with white folks about their whiteness and asking them to interrogate their whiteness, but they’ll ask this BIPOC and queer book to interrogate their otherness, but not interrogate their whiteness.

You asked them to target their whiteness. You get the ‘what do you mean?’ Because all of the other gets located in BIPOCness in queerness, but not in whiteness. If you start to interrogate whiteness white fragility. Yes. If you start to interrogate whiteness, what you end up with are conversations that have been displaced, that they get pushed out.

That they, I got black friends. Oh Lord.

These sentiments shine a bright light on the gulf between the critical and liberal lens. The experience of intersectional fragments make painful interrogations of one another across this divide. Any offer of equality is treated with suspicion, even disdain. In truth, there is no metric to prove that perceived discrimination is not real discrimination—therefore, an unwillingness to accept the legal guardrails against discrimination as sufficient.

[Related: “Truth in Children’s Literature: A Response to Dr. Siu’s American Ogres”]

What makes the therapeutic path of a safe space an unlikely cure, even if it were embraced, is the pernicious aspect of intersectionality: Asians, because of their success, become white-adjacent; alliances within the intersectional framework, such as with the pro-Palestinian BDS movement, have led to antisemitism. Coleman Hughes critiques this intersectional calculus:

Different forms of suffering cannot easily be quantified and compared. Rather than attempt what would be a difficult but interesting comparison, intersectionalists simply assert a priori that black men only suffer from one kind of oppression whereas black women suffer from three. This oversimplified, algebraic approach to prejudice ignores most of what happens in the real world.

The “logic” of intersectionality in a critical paradigm is “illogical” in a liberal paradigm. Understandably, the former prefers narratives while the latter prefers objectivity. These are different approaches to framing the social world.They are static conceptual models. Shelby Steele would ask us to appreciate the process in which change occurs:

The oppression of black Americans is over with. Yes, there are exceptions. Racism won’t go away — it is endemic to the human condition, just like stupidity. But the older form of oppression is gone … Before it was a question of black unity and protest; no more, it is now up to us as individuals to get ahead. Our problem now is not racism, our problem is freedom.

And, we would note, that the practice of freedom is rarely conducted in a safe space.

Conclusion

I admit that my attempt to defend the critical classroom would receive a C+ at best, regardless of the instructor’s lens. I cannot shake the notion that the quest to fix society through the critical classroom is dystopic. As interrogated in this two-part essay, the critical lens of DEI administrators, critical curricula, marginalized identities, and safe spaces seeks to scurry past constitutional protections, trades on a fragmented racial and gender calculus, and cannot risk the growing pains of a reforming liberal society.

Nevertheless, the critical lens plays a part in our educational, governmental, and non-profit institutions, not to mention permeating private business, entertainment, and media platforms. If our society falls apart, it will likely be from the tectonics of a critical lens.

“Ethnic conflict does not require great differences; small will do.” – Daniel Patrick Moynihan

And Hitler did some good things — I view this essay along similar lines. I don’t think you can separate anything from the larger fascism.