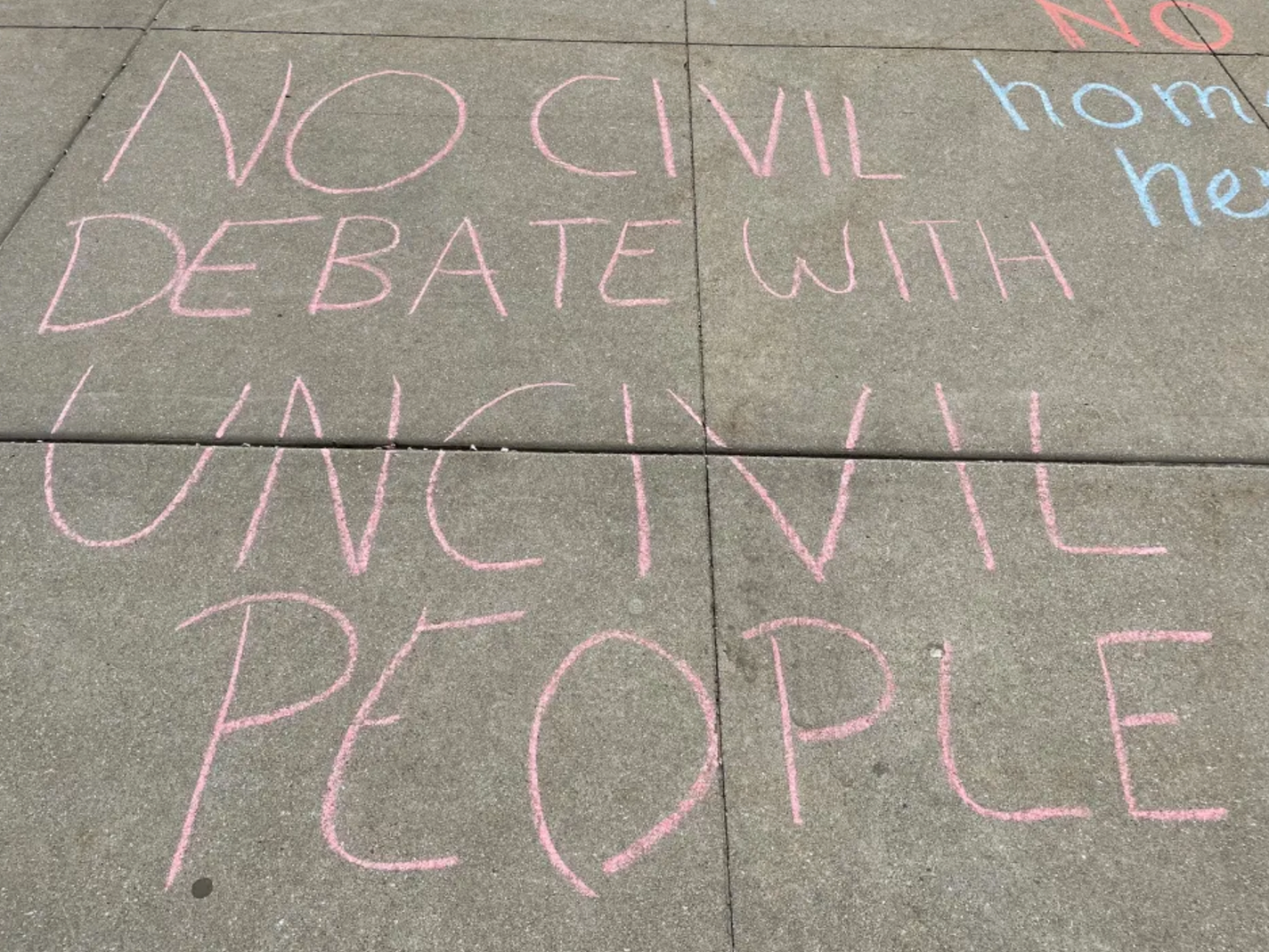

Law students at the University of Chicago recently used colored playground chalk to protest a conservative speaker. This raises the question: are they maturing adults or regressing adolescents? Perhaps philosophy has some lessons for how to understand the problem, and where to look for a solution.

One of my favorite philosophers is Robert Hanna. He specializes in the writings of eighteenth-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant and is a former professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. He now runs his own philosophy education and opinion site called APP (Against Professional Philosophy), as well as an online community called PWB (Philosophy Without Borders). Bob’s main argument, simplified here, is that philosophy is something with which all of us should engage; that all of us can “do” philosophy, and that it can be just as good, or even better, than what goes on in university philosophy departments.

Bob also holds strong opinions on what it means to think rationally, and how easy it is to fall into a number of intellectual and emotional traps that lead us away from mature, independent thought. We must address difficult questions without “fear or favor.” One of Bob’s best insights is that philosophy should deal with real problems. Problems always have a “philosophical” element, but they also provide the “vital substrate,” in the words of Karl Popper, without which we tend to be led astray by abstractions.1

We recently discussed the lack of mature thinking at American colleges and universities. I told Bob that, in my view, Kant has much to say about this, especially in how personal rights and freedoms must be linked to personal responsibility, and to our own “internal court of conscience.” This speaks to one of the biggest problems in higher education: the development of what might be called the “virtues,” which Aristotle and others spoke to centuries ago, and how they seem to be a distant ideal in academic culture.2

[Related: “You Are the Constitution”]

Here, Kant was perhaps among the first modern thinkers to address the free speech debate in terms of personal integrity. As Hanna puts it, Kant was a “dignitarian”: a human community is non-sectarian, sufficiently respectful of everyone’s human dignity, non-coercive, and non-authoritarian. “In the worldwide ethical community advocated by Kant, no one is ever treated as a mere means or a mere thing, or told that X is right just because the government says that it’s right & controls the means of coercion.”3

In addition to dignity, Kant provides two other critical, complementary ideals to which our colleges and universities should aspire, and which also provide a reasoned basis for asserting rights: they are duty (which I’ll speak to by way of an example, in a moment), and reciprocity (in a technical or network sense). Hanna elaborates: “Kant’s notion of reciprocal action = reciprocity is originally worked out in the first Critique, in the Third Analogy of Experience, which postulates simultaneous mutual causal determination as a fundamental structure of the real world. Some distinctive kind of causal structure is needed to hold the natural world together.”

Violating this three-part aspiration of rational behavior (prevalent in politics), creates many of the problems we see in higher education, because it leaves students (and faculty) without any kind of explicit mental and emotional model, and thereby leaves them detached from the realities of a functional society, which is central to the purpose of higher education. Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) is an example of this violation. It is one of many coercive “isms” that can distract us from critical thought. DEI, like critical theory, is essentially a psychological problem centered on adolescent thought patterns, which, if extended into adulthood, can manifest in an irrational obsession over personal identity, like a child fixated on his image in a mirror.4

Some of this problem for students (and many professors) goes back to Popper’s “vital substrate,” which must anchor their attention to real problems and real responsibility.5

In the history of the United States, it may be instructive to consider generations before us who were “grown up” by the age of 21. For example, an aircraft commander in World War II was at this ripe age the captain of a ten-man bomber aircraft, and often a group or even squadron leader, responsible for hundreds of lives and the conduct and performance of dozens of crews. Men and women who fought in or supported the American Revolution were also fully grown up, because they had to be. They were often supporting a family, growing their own food, tending to business matters, and otherwise fighting to survive.6

[Related: “Political Insanity on Campus”]

Perhaps that is part of the problem with many college and university students (unfortunately, it also extends into the military): a degraded sense of purpose and duty, and an aimless or confusing mission. This, too, goes back to leadership. Surely, it can’t be inspiring to hear America’s Joint Chiefs of Staff talk about race and identity, often as apologists who are more concerned with their careers and pensions than with leading and taking risk (and who are led, putatively, by a civilian commander who meets 25th Amendment criteria).

Edmund Burke, in his 1775 Speech on the Conciliation with the Colonies, described an American culture radically different than the one today. Burke observed the “untractable” spirit of the early colonists, who possessed the law as part of their powers of liberty and who were willing to actively advance these powers toward mature, productive ends.

America’s revolutionary mind is an expression of a moral law that flows from what John Adams called “the real American Revolution”; Jefferson called it “the American mind.” Is this mind still intact? If it is not, then it has fallen asleep after decades of comfort, complacency, and cultural decay: A mature, living law cannot stay alive in a dormant host or thrive in permanent adolescence.

1 “Genuine philosophical problems are always rooted in urgent problems outside philosophy, and they die if these roots decay.” – Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations.

2 Classical Greek philosophy’s virtue ethic of character development is based on self-determination, and the balancing of logos, pathos, and ethos, leading to telos (full potential and inherent purpose). That is, the strengthening of reason, or the “life of the mind” (logos), with compassion and a spirit of community. Those values stem from autonomous, self-directed judgment, not from institutional control.

3 Kant is appropriated by both the political Left and Right. In my view he speaks more in a “classical liberal” spirit. It may be wishful thinking to interpret his language with prescriptive progressivism (Nussbaum).

4 “The most dangerous allure concerns not just some personal nostalgic fantasies, but the past ages of unreason that humanity had only recently outgrown; a recidivism all too ready to regress to pre-Cartesian puerility. Though La Motte would like to believe that it is impossible for the modern world to fall back into the Homeric ‘imbecility of infancy,’ and though he scoffs at the idea that one might ‘claim to amuse grown men by the same fictions that would have charmed children,’ he knows that in reality adulthood slips easily back to infancy’s grip.” (Discours 22–23), in L. Norman, The Shock of the Ancients (173).

5 A philosophical solution to excessive abstraction in many higher education settings may be American pragmatism: Chicago’s Dewey, Peirce, James, and Mead, and Harvard’s St. John Green, were focused on tough economic-development problems in their local communities in the rough and tumble of early-twentieth-century America.

6 It is interesting to compare this example of leadership with Kant’s bases in duty, and his similarities with the Stoics. See J. Visnjic, Kant and the Stoics, in The Invention of Duty.

The problem is so many kids nowadays arrive at college not knowing why they are there. (I graduated from high school. Now what? Well then, might as well go to college…)

It’s not just law students. This cohort of undergraduate students is the most immature, coddled, and ungrateful of any in recorded history. They feel entitled to have their every whim addressed. The problem is we have woke cowards running these universities who absolutely refuse to tell these petulant children to go pound sand or find some other school. Until this happens, things are only going to get worse.

We desperately need to repeal the 26th Amendment. It ranks up there with the creation of the EPA as one of the most foolish things ever done.

The 26th Amendment is not the problem by itself. The problem is that the age of adolescent behavior rose; if it keeps rising, we will be in trouble no matter what the voting age is.

But what is acceptable when a speaker is thought to be contemptible? Shouting them down is not correct but signs are perfectly fine. You are not allowing for reasonable dissent.