In 1753, English writer Samuel Richardson has his main character proclaim, “Women must not encourage Fops and Fools. They must encourage Men of Sense only.”

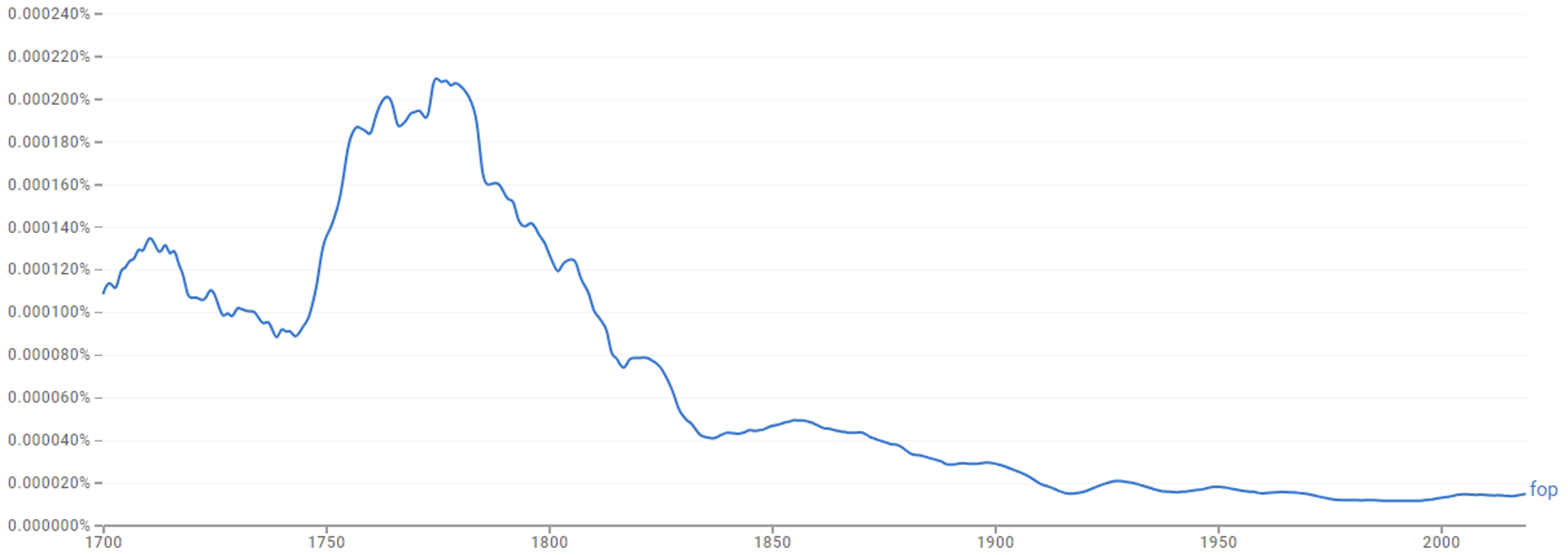

While “fool” belongs to most English speakers’ lexicon today, “fop” likely does not. According to Google Ngram (below), “fop” has seen about a 95% decline in relative usage since its heyday in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. That is a shame. The fops are still with us, and they have found a comfortable living in academia.

Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary defines a fop as a person of “much ostentation; a pretender.” A 1759 dictionary states that this ostentation appears in “dress, speech, and behavior.”

People disapproved of such “foppery” on several grounds. First, it was deceitful. David Hume wrote of politeness in his day that it “runs often into affectation and foppery and disguise and insincerity.”

It was also delusional. Shakespeare had Edmund in King Lear say, “This is the excellent foppery of the world that, when we are sick in fortune, (often the surfeits of our own behavior) we make guilty of our disasters, the sun, the moon and stars.”

It was often detrimental to one’s aims. “Picking up choice words, and clothing a sentiment in tinsel foppery” produces that which would have been “more forcible if left naked and unadorned.”

It was frequently destructive to the self. “While the body is decked in all the fantastick modes of foppery, the mind is insensibly withdrawn from all glorious operations.”

Based on these views, foppery was seen as a grave moral defect, a sin. It was listed among lust, drunkenness, envy, covetousness, ambition, anger, idleness, and pride.

Today, academia may benefit from imitating those in our intellectual heritage who strongly opposed foppery—specifically as it applies to writing.

The Teachings of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres

In writing, foppery took several forms. For example, it often showed flowery French influences or used bombast and jargon. Its character was that of trying too hard to appear profound, creating illusions of greatness.

Reforms can be found in the seventeenth century among leaders of the English scientific revolution. Thomas Sprat observed in 1667 that The Royal Society of London adopted a “resolution to reject all the amplifications, digressions, and swellings of style: to return back to the primitive purity, and shortness, when men deliver’d so many things, in almost an equal number of words.”

The society sought “positive expressions; clear senses; a native easiness: bringing all things as near the Mathematical plainness, as they can: and preferring the language of Artizans, countrymen, and Merchants, before that of Wits, or Scholars.” In this anti-scholarly manner, these emergent “scientists” humbly subjected themselves to scrutiny and therein achieved the unimaginable: making the scientific method (as an approach to truth) palatable.

The reforms continued in the eighteenth century, especially within the internationally renowned Scottish universities where a decidedly new teaching of “rhetoric and belles lettres” took place. Gone were tropes and literary gadgets. In were natural expressions, exactness, conciseness, and simplicity.

Adam Smith and Hugh Blair, in particular, gave influential lectures on the subject. Smith warned against writing foreign, stiff, perplexed, and off-putting text full of “dungeon[s] of metaphorical obscurity.” Blair advised against text with ornament and complexity, which “required a peculiar turn of genius to pursue.”

The most important goal of academic writing was comprehension. A text should be “easily apprehended by all.” Better yet, it should be “understood with ease … even by the most negligent and inattentive.”

The Foppish Tower

Contemporary instruction certainly bears resemblance to these prior teachings. It regularly advocates for clarity and advises against jargon. Yet foppery is something beyond these. It is what the great Deirdre McCloskey is takes aim at in Economical Writing and The Rhetoric of Economics. It is the subject of Nobel Prize winner Friedrich Hayek’s The Counter-Revolution of Science. Foppery combines the vices of conceit, vanity, and deception. When complexity contains foppery, it becomes a nest for pedants, a pond for narcissists, and an oil for grifters.

In contemporary academic writing, complexity is a known problem, but a perusal on any given day reveals plenty of foppery as well.

For example, on the great novelist Jack Kerouac, I find an oft-cited paper chock-full of statements such as, “Preceding the postmodern literary and cultural advent it delineates, Kerouac’s work clarifies the postmodern cusp.”

This would have undoubtedly been called foppish writing. It garishly overdresses a simple and ultimately mundane point.

On the effects of fair-trade coffee, I find a paper with the claim that research has produced “a long catalogue of cases documenting the rough incursion or intensification of capitalist relations into new spaces.”

Here are “foplings” (fops of a “second order”) in action. They are using overdramatic language instead of providing conceptual clarity and exposing their ideas to broader scrutiny.

Finally, on a state university’s new general education requirements, I find this learning objective: “Students will examine notions of justice amidst difference and analyze and critique how these interact with historically and socially constructed ideas of citizenship and membership within societies, both within the US and/or around the world.”

These authors, I dare say, are “fopdoodles.” While they may have an honorable goal, like their doodle-dandy cousins (of Yankee fame), I wonder how many readers can intelligibly navigate this pedagogical landscape of notions interacting with constructed ideas amidst differences (their words, not mine).

Sadly, in none of these examples can I properly judge the merit of the ideas. The writing, to use Blair’s description of foppery, is “frivolously rich in Style, but wretchedly poor in Sentiment.” The authors come across as academic versions of the ridiculous seventeenth-century character, Sir Fopling Flutter, who carefully tended his “exactly curl’d” periwig and affected French lisp.

An Institutional Agenda

Can we fight against foppery? While impenetrable writing may betray a deficiency of skill, foppery is perhaps better understood as a deficiency of character—a moral flaw. The former may respond to training; the latter almost certainly needs something more. Adam Smith had some ideas for reform.

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith proposed that social interaction was often the correct means for moral teaching. “An amiable action, a respectable action, an horrid action, are all of them actions which naturally excite the love, the respect, or the horror of the spectator.” When the spectator reacts to these natural “excitements” and expresses approval or disapproval, “general rules” of moral behavior tend to emerge.

Smith’s observation may be a simple sociological point today, but it is still worth contemplating for a moment. It leads to the following directive: If you find foppery horrid, express your innate horror. We are advisors, mentors, friends, colleagues, committee members, peer-reviewers, and administrators—the impetus for change comes through these connections, by our bravery to both spectate and speak.

Simply said, when you see a bad actor, identify that actor in moral terms. To this end, I make the small contribution of a word—fop. It is not a bad choice. It is a simple three-letter word that enters the brain with almost immediate intelligibility to label something vicious to our virtuous pursuits. It is time to start talking of fops again.

Quote: “…the impetus for change comes through these connections, by our bravery to both spectate and speak.”

Sounds kind of fop-ish to me.

Kidding

Hey, that portrait at the top is of Samuel Richardson, right? He looks like a fop to me!

Right click the image and click google search the image and you’ll get the name Adam Smith, not Samuel Richardson. You must have a modern university education. [What did you censors do with my previous comment? Kevin]

How sad to learn that Adam Smith looked like a fop!

And yes, the modern university skimps on google, yes indeed!