The nation’s 250 Anniversary is only 29 months away. The National Association of Scholars is commemorating the events that led up to the Second Continental Congress officially adopting the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. This is the second installment of the series. Find the first installment here.

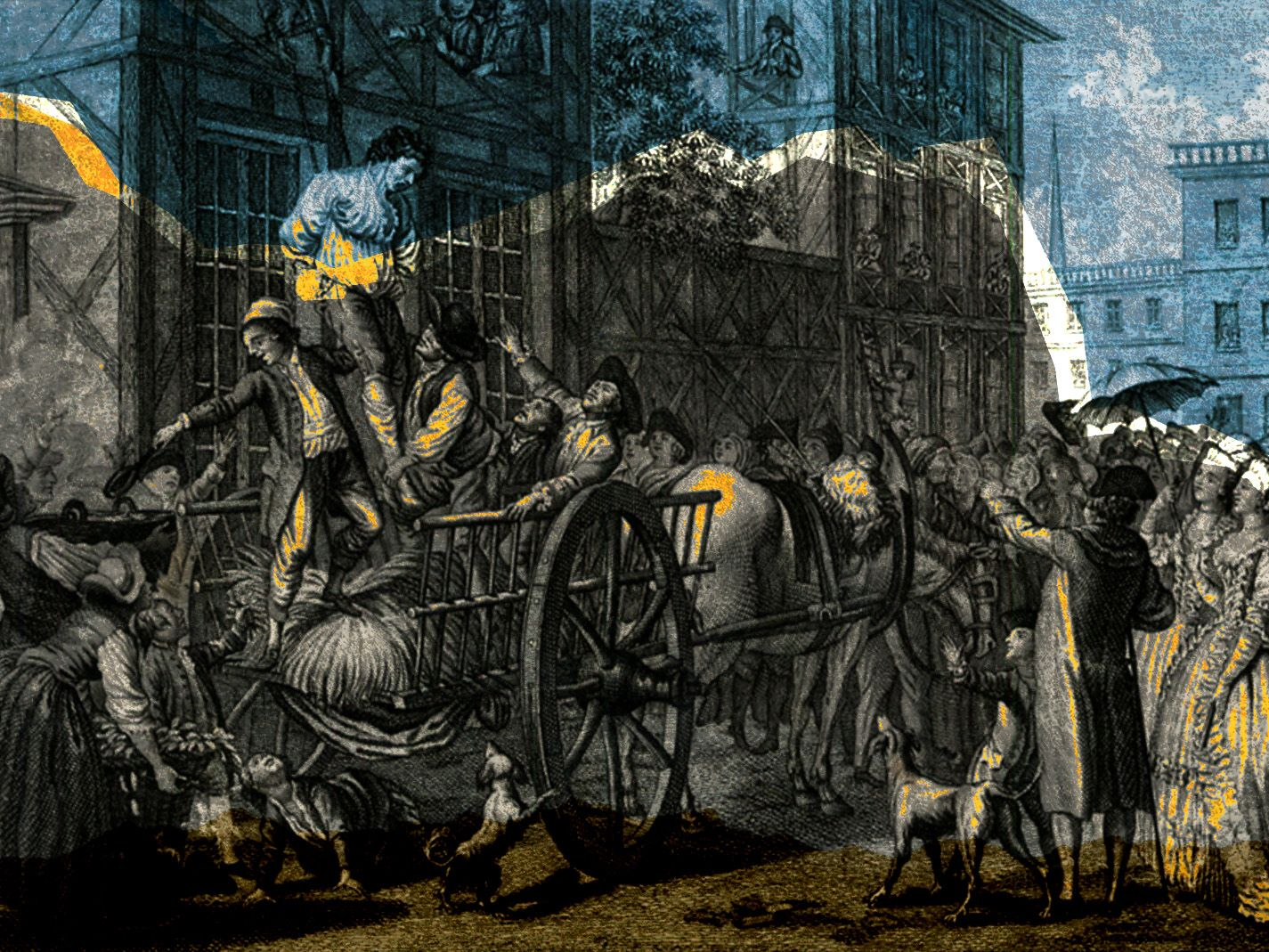

Last month, we celebrated the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. This month, we return to Boston for the anniversary of an event that Patriots are a little less proud of: the tarring and feathering of Loyalist John Malcolm.

Gallery

Hunter Biden — Energy Expert and Entrepreneur — Wikimedia Commons

Merrick Garland — U.S. Attorney General — Wikimedia Commons

Rachael Rollins — Soros-backed district attorney for Suffolk County, Massachusetts, 2019-2022 — Wikimedia Commons

Alvin Bragg — New York County District Attorney — Wikimedia Commons

Chesa Boudin — District Attorney of San Francisco, 2020-2022 — Wikimedia Commons

Kim Foxx — Cook County State’s Attorney of Chicago, 2016-2023 — Wikimedia Commons

John Malcolm

Are some people above the law? Able to get away with crimes because of their connections to powerful officials? Are some officials inclined to turn a blind eye to crimes committed by favored individuals? Or ready to condone the misbehavior of their subordinates if that behavior advances their political agenda?

If unequal justice becomes too common or too flagrant, the public eventually loses patience. Vigilante justice is one response, and such vigilantism is an early warning sign of revolutionary fervor. Why support a government that is through-and-through corrupt?

These considerations had become so clear to people in Boston in the weeks following the Boston Tea Party that they took matters into their own hands on the evening of January 25, 1774.

Earlier that day, the Loyalist tax man John Malcolm knocked George Hewes on the head with a cane, leaving him unconscious on the street. Hewes, a shoemaker, was a well-known adherent of the Patriot cause and had been among the “Indians” who had thrown chests of British tea into Boston Harbor on the night of December 16. But that’s not why Malcolm attacked him.

What provoked Malcolm was that Hewes had intervened when Malcolm was about to strike a child with his cane. They argued, Malcolm, telling Hewes that he shouldn’t interfere with the “business of a gentleman.”

This was intended and received as a class distinction. Malcolm was a sea captain and British officer; Hewes, the shoemaker, was merely a tradesman.

But Hewes knew a few things about Malcolm, whose reputation as a zealous enforcer of the hated tea tax had spread through the colonies. In November, sailors in Portsmouth, New Hampshire had seized Malcolm and tarred and feathered him. Hewes replied to ‘gentleman’ Malcolm something to the effect that at least he, a mere shoemaker, hadn’t been tarred and feathered. At that point, Malcolm struck Hewes on the head with his cane, knocking him out cold. Malcolm then went on his way, confident that the law could not touch him.

The law couldn’t, but the Patriots could.

They knew full well that British officials could literally get away with murder. They knew that four years earlier, customs officer Ebenezer Richardson shot and killed a twelve-year-old boy, Christopher Seiders. Richardson was tried for murder and found guilty by a jury, but the judges delayed passing a sentence and the matter was hastily referred back to Britain with the result that Richardson received a royal pardon. What hope had the Patriots that Malcolm would be held accountable before the law?

In any case, they showed up at Malcolm’s house that evening, seized him, stripped him to the waist, tarred and feathered him, and then took him to the Liberty Tree, forced him to drink a lot of tea, threatened to hang him, and proposed to cut off his ears. The last threat broke his defiance, and he mouthed the anti-royal words they demanded he say. A Boston newspaper two days later reported the crowd demanded he renounce his commission and “swear that he would never after hold another inconsistent with the liberty of his country.”

So, his is a story of torture by a mob in an instance where the public had lost confidence in government-dispensed justice. The story was widely reported and amplified the passions on both sides.

Fortunately, today no American fears that we live under a two-tier justice system. No one harbors misgivings about how the Attorney General of the United States conducts business. No one thinks our district attorneys are refusing to enforce the nation’s laws. Well, maybe not no one.

What’s Next?

In 1774, Benjamin Franklin, as Postmaster of the Colonies, sought to persuade the British government on the Massachusetts petition against Governor Hutchinson and Lieutenant Governor Oliver. With mysterious sources, Franklin exposed their intentions through leaked letters, sparking public furor and a petition for removal. Facing character attacks, Franklin stayed composed, but the petition was rejected, leading to his firing and transformation into a revolutionary. Learn how personal slights fueled the American Revolution in the upcoming article set to be released on January 29!

Editor’s Note: In the weeks and months to come we will post on Revolutionary events large and small, and we will do so in a high-spirited manner appropriate to the men and women who liberated America from the tyranny of the British crown.

Art by Beck & Stone

There is more to John Malcolm — the Colonial Society of Massachusetts have some interesting details at https://www.colonialsociety.org/publications/4959/reconvening-general-court-and-tarring-and-feathering-john-malcolm and https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/638

It appears that he had been dismissed from a customs position at Currituck, North Carolina because of corruption, returned to Massachusetts and then was appointed as a deputy customs position at what is now Portland, Maine — Maine then being part of Massachusetts.

In that capacity, he seized a ship in the Sheepscut River for some minor discrepancy in its registration paperwork. That would have been Wiscasset, which is about 40 miles further north by road. While the ship was released from Portsmouth (New Hampshire and on the Piscataqua River), it was “the Sailors at Sheepscut River” who tarred & feathered him, and I’m inclined to believe that happened in Wiscasset.

This makes more sense because the Royal Governor in New Hampshire — John Wentworth — was way more reasonable than Massachusetts Governor Hutchenson and hence there wasn’t the revolutionary fervor in Portsmouth that there was in Boston and some parts of Maine. (It was Wentworth who understood that a lot of the tall trees reserved for Royal Navy masts were in places where they could never be gotten out of the woods intact, so he reported them as “damaged in a storm” and let people cut them down for lumber.)

What’s not mentioned about Ebenezer Richardson and his shooting of the 12-year-old boy is that it took place in the midst of a riot. A mob was attacking Richardson’s house, breaking his windows (which were very expensive at the time) and he fired his blunderbuss from inside the house in an attempt to defend it — as the law permitted at the time. Said 12-year-old boy was in the process of picking up a rock when he got shot — a situation remarkedly similar to the shooting of Ashli Babbitt on January 6th…

What was it that President Biden said about firing a shotgun to defend your home?

And what’s rarely mentioned about the American Revolution, at least in Massachusetts, is that it was way more complicated than a lot of people realize. Only a third of the population supported the Patriot cause, a second third supported the British, and the remaining third wished it would all go away — sort of like politics today. January 6th was remarkedly similar to a lot of the things that were happening in Boston prior to the Revolution — with both sides viewing the other as somewhat less than human, a situation we also are dealing with today.

What is it that George Santana said about history???