The nation’s 250 Anniversary is only 29 months away. The National Association of Scholars is commemorating the events that led up to the Second Continental Congress officially adopting the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. This is the forth installment of the series. Find the third installment here.

Joe Biden — Photo by Gage Skidmore — Flickr

January 6th Crowd — Photo by TapTheForwardAssist — Wikipedia

Merrick Garland — Senate Democrats — Flickr

Alejandro Mayorkas — Photo by Zachary Hupp — Department of Homeland Security

Tucker Carlson — Photo by Gage Skidmore — Flickr

What happens when a politician full of restless malice and disappointed ambition uses his power to inflict dire punishment on his opponents? What if he misreads a populist protest as an insurrection and imposes measures that harm a whole country? This is what happened in the Spring of 1774.

Dissatisfaction with British rule among the American colonies was long-standing, but in 1773 and early 1774, it increasingly broke out in dramatic form. First came the Boston Tea Party in December. Then, in January, Bostonians had tarred and feathered Loyalist tax man John Malcolm. Benjamin Franklin, who had been sent to London to appeal for leniency, was instead publicly humiliated before the Privy Council in London. In February, irate citizens of Massachusetts impeached (and then ostracized) the chief justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court, Peter Oliver, whom they accused of being an agent of the Crown.

Outwardly, March 1774 looked like a lull in the distempered times, but it wasn’t. On March 14, an enraged Prime Minister, Lord North, asked parliament to close the port of Boston. His proposal was the first step in what became a series of reprisals by the British for America’s populist defiance of his tax policies. Parliament passed “The Boston Port Act” on March 31—the first of the so-called “Coercive Acts,” rebranded by the patriots as the “Intolerable Acts.”

Americans had caught wind of North’s revenge before the Boston Port Act passed. Newspapers had been arriving from London all during this period, including one carrying the news from the day after North introduced his proposal to close the port.

This played into the hands of John Hancock, ever eager to fan the flames of rebellion.

In early March, Hancock counseled Americans to fear the “restless malice and disappointed ambition [of] our inveterate enemies.”[1] In that light, he urged creating a “Council of Deputies” representing all the colonies. It would meet to lay “a firm foundation … for the security of our Rights and Liberties; [and a system] for our common safety.” Hancock’s idea had precedents but, in the wake of Lord North’s aggressive action, this time in caught fire. The First Continental Congress would not convene until September, but North had lit the fuse.

Lord North’s proposal also wrong-footed the more temperate patriots.

John Adams, for example, had expected a British reaction to the Tea Party, probably in the form of requiring Massachusetts to pay for the dumped tea. The escalation of closing the port and ruining the Boston merchants appalled the public and gave Hancock’s faction proof that no good would come from efforts to reconcile with the Crown.

Hancock had begun the month with a speech on the third anniversary of the Boston Massacre, which has come down to us as his “Boston Massacre Oration.” In it he speaks of his “hearty detestation of every design formed against her [his country’s] liberties,” and the “duty of every member of society … strenuously to oppose every traitorous plot which its [his country’s] enemies may devise for its destruction.” He says civil government’s purpose is the security of persons and property—a principle so self-evident that attempting to argue it would be like “burning tapers at noonday, to assist the sun in enlightening the world.” He vows his “eternal enmity to tyranny,” but leaves it to a series of rhetorical questions whether the British administration of the colonies is indeed tyranny. That series of questions is the template for Jefferson’s long list of indictments of Britain that would appear 27 months later in the Declaration of Independence.

But my summary covers only the more temperate part of Hancock’s oration. When he gets to his account of the Boston Massacre itself, Hancock lets fly with the vehemence of one of the Puritan forefathers:

Ye dark designing knaves, ye murderers, parricides! how dare you tread upon the earth which has drunk in the blood of slaughtered innocents, shed by your wicked hands? How dare you breathe that air which wafted to the ear of heaven the groans of those who fell a sacrifice to your accursed ambition?

Having reminded his audience of the injustices suffered by the colonists under the British yoke, Hancock recovers in time to express his confidence in the revolution to come: “I have the most animating confidence that the present noble struggle for liberty will terminate gloriously for America.”

His words were no doubt still ringing in Bostonians’ ears when word arrived that Lord North proposed using the British navy to shut the Port of Boston.

Did Hancock exaggerate? Not doubt. And Lord North may not have been all that bad. A friend tells me North was not “activated by restless malice.” He was, rather, “a ditherer oscillating between soft and hard policies.” Hancock needed a well-defined enemy and North met his purpose.

But North’s use of collective punishment really does gall. When President Biden barks at the half of America that didn’t support him in 2020 as the “MAGA Republicans” or Garland prosecutes even the most innocuous “J6ers,” they indulge the genuine Northian impulse. Just as Trump finds his inner Hancock when he declares, “They’re coming for you: I just happen to be in the way.”

John Hancock: A poem by David Randall, Director of Research at National Association of Scholars

John Hancock, Esquire, at your service;

A shipper to ports near and far.

I pay all my duties in daylight,

But less ‘neath the cloud and the star.

That demagogue Hancock! they call me—

It’s true I can speak a fair while.

The poor folk, and me, don’t like redcoats,

Though some fine folk will give them a smile.

Ye murdering, blood-drinking parricides!

Ye rulers by whip and by rod!

Ye red-handed slaves of ambition

Shall be judged at the great bar of God!

Let us work in the struggle for freedom

Which hath full consent of our hearts.

We shall win, for in all causes righteous

God’s providence will play its part.

I wouldn’t say that over supper;

It’s the tone for a public oration.

But a man suits his tools to his labor:

By such words we shall make a new nation.

[1] Quoted in Mary Beth Norton, 1774: The Long Year of the Revolution. Knopf, 2020, p.76.

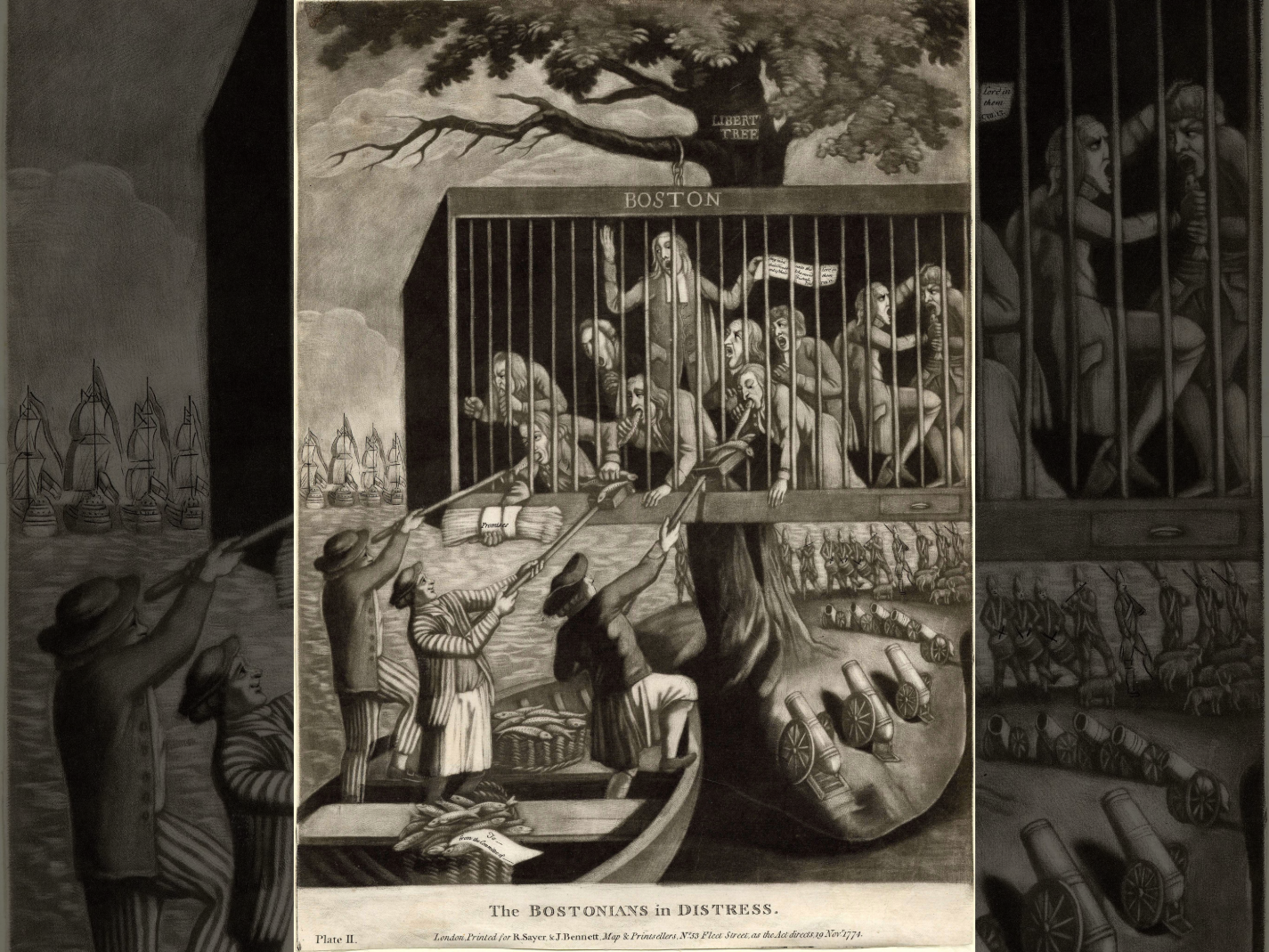

Photo available at Wikipedia — The Bostonians in Distress mezzotint 1774.jpg

“Dissatisfaction with British rule among the American colonies was long-standing”

It’s not that simple – nor as universal. BOSTON had problems that other places didn’t, and they really weren’t as longstanding as one might think.

It really started with the Seven Year’s War (1756–1763) which was a major British victory — Quebec fell to the British in the 1759 Battle on the Plains of Abraham and that essentially was the end of the French in North America. But wars are expensive and the real question was who was going to pay the war debts.

The Crown felt that it had defended North America and hence the people living in North America should pay, while they felt that they had served the King and fought (and died) in the King’s war and hence it was outrageous for the King to turn around and send them the bill.

There was more to it than this, though — wars always stimulate the economy because the military is purchasing food, clothing, and munitions. There is also a multiplier effect, e.g. more sheep are needed to have more wool shorn off them, to be processed into more yarn to be woven into more fabric from which to make more blankets from — with all these people having more money to spend on other things. A war also reduces unemployment by removing young men from the workforce.

The opposite happens when the war ends. There usually is a recession because the military isn’t buying all the stuff it once was, and tries to pay its bills — along with unemployment when the soldiers come home and look for work. That was the situation in Boston, except that it was badly exacerbated by one other thing — off-duty British soldiers were permitted to work for money — mostly as longshoremen. Like the illegal alien of today, because the soldier’s food, clothing, and housing was already being provided by the government, he could afford to work for a lot less than the local laborers and did.

This depressed the wages of the working poor in Boston and is what led to the so-called Boston Massacre. I think that North was trying to punish the longshoremen when he closed the Port of Boston — but the whole thing was incredibly stupid and makes no sense when one looks at the economy of the era (which North probably didn’t know).

The largest import (by volume) was firewood which was cut along the coast of Maine and sailed down to Boston. Fireplaces were (are) woefully inefficient and one would burn 40 cords of wood a winter — a cord is 4′ x 4′ x 8′ — ten of them would fit on a flat-bed trailer truck (8′ x 40′) so we’re talking four trailer truck loads. To put this in perspective, the average home heating oil truck holds 3,500 gallons and few people burn more than 500-600 gallons in a winter.

It was cut along the coast of Maine, which was then all old-growth Oak & Maple, because it was far easier to sail it down to Boston (from as far as the Canadian border) than to lug it in 15 miles over the atrocious roads of the day. And people did this because grains did not grow along the foggy coast of Maine, so they traded for flour and hard currency which they then used to purchase other items (included European goods).

Grain did grow in Massachusetts once you got away from the coast, tobacco is grown today in the Connecticut River Valley, and there wasn’t the same need that there was in Maine — a point John Adams made to Abigail as to why Maine would not support the Revolution, and it didn’t.

What’s inevitably missed here is who had the hard currency in the first place — the British and those who were associated with them. The Revolution was very much an economic revolution as well, the middle class rose up to overthrow the upper class. But it was the British who were unable to buy firewood and more portable goods could be unloaded at a dozen other ports or in the dark of the moon on a beach — Revere and Old Orchard Beaches come to immediate mind.

The people most hurt by the closing of the Port of Boston were the wealthy Loyalists — and that really was a blunder on North’s part.

I am not entirely sure why commemorations of the 250th anniversary of Independence appear at MindingTheCampus, but they are welcome. I am less sure why the author needs to link them to recent events. “MAGA” is used by its leader as a term of pride. Even if some of the rioters have been overcharged, that would be analogous to overcharging participants in the Boston Tea Party, not closing the entire Port of Boston.

They didn’t have they didn’t have facial recognition technology (or even photography) back in 1774, they also didn’t have credit card records or cell phone tower pings. As late as the 1990s, it simply wasn’t possible to tell who the members of a mob had been.

They also didn’t have a DC Jury — in Boston it would have been jury nullification, no Boston jury was going to convict them. (This is why taking accused British officials to England for trial became a practice — and condemned as such.)

The think I always wondered about was International Law which requires any nonbelligerent vessel be given access to a “harbor of safe refuge” and that includes the ability to obtain supplies (water, food) and to make repairs (replace broken masts).