Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Real Clear Wire on March 20, 2024 and is crossposted here with permission.

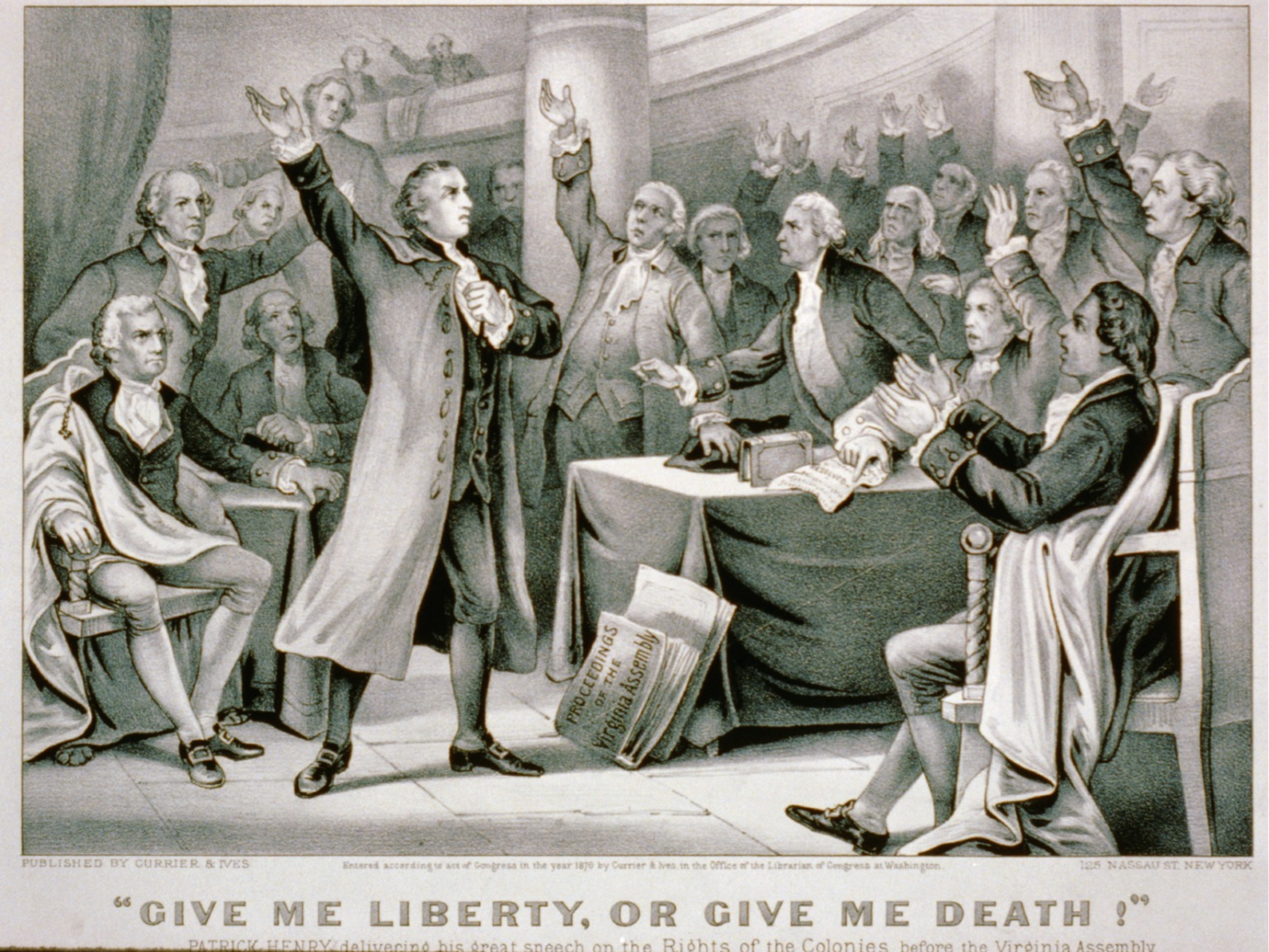

On March 23rd in 1775, Patrick Henry rose at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, to urge his countrymen to arm themselves for the Revolutionary War. Four weeks before the battle of Lexington and Concord, Henry saw the future: “The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms!”

Most Americans remember the stirring ending of Henry’s speech: “give me liberty, or give me death!” But in this election year, it is useful to be reminded of the beginning of that speech.

When Henry rose to speak, he knew he would be called a warmonger and disloyal to the still well-loved King George. He knew that even many patriots would oppose arming as premature and provocative.

But facing such a momentous decision, he decided he must speak, whatever the risk. “Should he keep back his opinions at such a time, through fear of giving offense, he should consider himself guilty of treason toward his country.” The question that the Virginia Convention faced could lead to war. At such a critical juncture, it was “no time for ceremony” but time for a lively debate in which everyone openly voiced their concerns.

He reminded the gathered delegates that “we have done everything that could be done” to seek a peaceful solution with Britain. “We have petitioned – we have remonstrated – we have supplicated – we have prostrated ourselves before the throne” of King George. But now, with no other options for redress, the delegates elected by their neighbors needed to decide if they should take a drastic course of action.

This is a critical point. When Henry announced his commitment to “liberty … or death” he was not attacking all government regulation or control, demanding personal liberty regardless of society’s interests or needs. He was not some mad libertarian chafing at the decisions of his elected representatives.

The problem the colonists faced was that they had no vote in Parliament. In more familiar terms, the problem was not simply taxation – but taxation without representation.

Now the people’s representatives must decide for themselves and their constituents what to do.

We know the rest of the story. As Henry’s speech rose to a crescendo, he asked in an almost accusatory tone, “Is life so dear; or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains, and slavery?” His final remark would reverberate across America as the king’s former subjects rose to demand the rights of citizens: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”

Today, we enjoy the liberty for which Henry and his colleagues fought. But Henry did not see it as liberty to do whatever one wants, but liberty to join with other citizens to make laws and ensure freedom for the whole community.

This was never more clear than in Henry’s final political campaign in 1799. He had been a leading Antifederalist who had warned that the new Constitution would create a government too powerful and distant from the people. But he came out of retirement at George Washington’s behest to defend the Constitution against the radical idea of state nullification of federal laws.

Henry insisted that since “We the People” had adopted the Constitution, opponents of federal policies must act “in a constitutional way.” Go to the ballot box, he told his supporters. The alternative was “civil commotions and intestine wars” ending in “monarchy.”

Today, our nation faces enormous challenges. I think Henry would repeat his admonition from 1775 and urge us to speak up, to join the debate. I am confident, too, that he would repeat his warning from 1799 that we must act with other citizens to seek reform “in a constitutional way;” the alternative is “monarchy,” which he had come to dread.

When Henry died a few months after that final speech, a piece of paper was found with a message to the citizens of the United States. He reminded Americans of his Stamp Act speech that, according to Thomas Jefferson, gave “the first impulse to the ball of the revolution.” But Henry understood that it would take work to keep the nation afloat. A monarchy was, after all, easy: You just do what the king says. But as Benjamin Franklin reportedly said after the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, the United States has “a republic – if [we] can keep it.”

Photo by Currier and Ives — Wikipedia

The difference between a “republic” and a “democracy” was illustrated in Danvers (not Salem) Massachusetts back in the 1690s. We can get into all the underlying stuff that was involved, including the fact that Danvers (“Salem Village”) didn’t want to be part of Salem anymore — but that Salem wanted their tax dollars and unpaid service as nite watchmen in Salem — and not in Danvers, where they owned property.

Forgetting all of this, the “Salem” witch trials (which were held in Salem) is a classic example of democracy run amuck — it only ended when they accused the Royal Governor’s wife of being a witch — at which point the Governor abolished the court system and replaced it with the one that exists to this day.

I was at UMass when they were chanting “Fuck the First Amendment” — I’ve seen what mobs are capable of and it is scary. The French Revolution had an engaged electorate and that didn’t turn out so well — what I am trying to say is that “a just and moral people” can be trusted with democracy — but I am not so sure we have such a populace anymore.