Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Law & Liberty on May 16, 2024 and is crossposted here with permission.

The summer of 2020, when George Floyd’s murder inspired America’s “racial reckoning,” seems a distant memory. Although talk of a right-wing backlash is often overstated, we have witnessed some effective pushback against left-wing identity politics from the right. “Wokeness,” as it is sometimes called, is not defeated, but it has faced meaningful headwinds in recent years. At times, this has gone too far. In response to the left’s recent excesses, many on the right seem eager to embrace their own forms of identity politics. Some elements of conservative media have turned towards a harder-edged right-wing vision, and this development is worth watching closely.

Other voices, however, maintain a principled opposition to our race-obsessed political culture, holding firm to individualist and meritocratic principles. Coleman Hughes has recently emerged as a leading proponent of this vision, and his new book, The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America, is a thought-provoking manifesto. Although it is not the most original work on this subject, it does raise important points that Americans—of all racial and ethnic backgrounds—should seriously consider.

The book is not a work of navel-gazing, though Hughes does provide some autobiographical details to help readers understand his perspective. As the son of an African American father and a Puerto Rican mother growing up in New Jersey, he notes that his childhood was not characterized by racial obsessions. When he transferred to a private school with few black students, he admits he was viewed as something of a novelty, and his classmates were not always paragons of racial sensitivity—he was especially annoyed by their strange eagerness to feel his hair, for example. He nonetheless recounts that their curiosity about him was not driven by malice, and navigating a majority-white environment was not especially challenging.

It was not until Hughes, as a teenager, attended a “People of Color Conference” that he was informed that his racial classification should be central to his sense of self: “My blackness was instead considered a kind of magic. My skin color was discussed as if it were a beautiful enigma at the core of my identity, a slice of God inside my soul.” When he later enrolled at Columbia University, he learned America’s elites were obsessed with race, to the detriment of intellectual life and people’s ability to treat each other as genuine equals.

According to Hughes, American race relations are increasingly poisoned by the ideology he calls “neoracism.” This perspective, he argues, “insists that sharp racial classifications are a necessary part of a just society.” He does not deny that old-fashioned white supremacist attitudes still exist in America today, but he suggests that this older variety of racial animus no longer possesses real institutional power.

Perhaps more importantly—although neoracists have reversed the direction of racial invective, primarily targeting white people in the name of social justice—the two racisms share more in common with each other than with the colorblind ideal: “Neoracists and white supremacists are both committed to different flavors of race supremacy. They both deny that all races are created equal. They both agree that some races are superior to others, and they both agree that not all people deserve to be treated equally by society.”

Readers familiar with how the center-right has approached these kinds of issues for the last several decades will find little here that is genuinely novel. It is hard to make new arguments for colorblindness, or for the virtues of treating each other as individuals and rejecting the politics of historical grievance. This is not a criticism of Hughes. Old arguments, to the extent that they are correct and persuasive, should be regularly restated and updated to reflect contemporary situations.

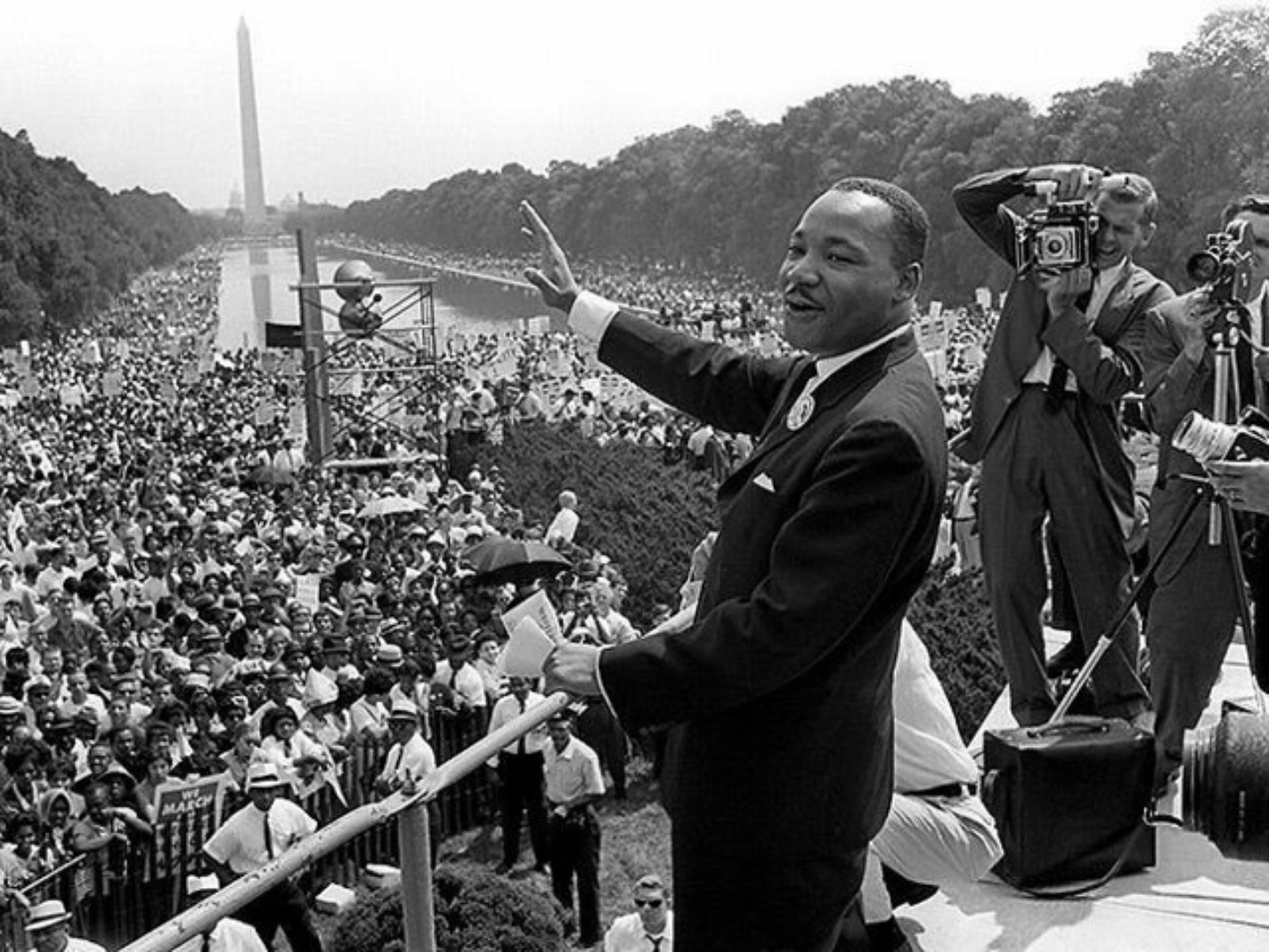

Hughes acknowledges that his thinking is inspired by Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, and other civil rights leaders from earlier generations. As many conservative commentators have noted, the vision King promoted in his most famous speeches and writings was abandoned by his successors, who dismissed the colorblind ideal. I am generally uninterested in debates about what Martin Luther King (or any other important historical figure, for that matter) would think about today’s controversies. This is largely because, when considering very prolific writers, one can find quotes that seem to endorse many different and sometimes contradictory positions. Hughes nonetheless makes a persuasive argument that his position is the one most aligned with the principles early champions of black civil rights promoted.

A few of Hughes’ arguments stand out as noteworthy. His point that race is a crude proxy for disadvantage warrants serious consideration. He notes, for example, that about one-fifth of contemporary black Americans are first- or second-generation immigrants. It makes no sense to treat these black Americans as victims of slavery, in need of restitution. He suggests it is a mistake to treat African ancestry, as such, as synonymous with persecution and subjugation, a mistake that can introduce new injustices and resentments into American life.

So-called racial justice advocates do not follow any kind of consistent principle when it comes to addressing racial disparities.

Hughes also makes a broader compelling argument about the use of aggregate statistics when thinking about our individual circumstances and the different forms of oppression we may suffer. As individuals each living our own lives, nationwide statistics may have scant relevance to us: “We don’t experience our lives in terms of averages. We only ever experience our lives as unique individuals interacting with other unique individuals. If you’re a white employee working for a black boss who exploits you in some way, what good is it to say that, on average, whites are more likely to be bosses?”

Hughes does not deny that, on many metrics, minority groups, on average, suffer more than white Americans. He reasonably notes, however, that so-called racial justice advocates do not follow any kind of consistent principle when it comes to addressing racial disparities. Neoracists express outrage whenever a metric suggests blacks are at a disadvantage, and they insist that the state must intervene to correct this injustice. As thinkers like Ibram X. Kendi argue, any major disparity between racial groups can only be explained by racism. By that logic, however, these same ideologues should be alarmed and incensed by the fact that white Americans have a higher suicide rate than black Americans. Their silence on issues where whites are not advantaged suggests their real agenda: “a program in which all racial disparities must be eliminated except those that benefit people of color.”

Beyond his commitment to colorblindness, Hughes tells readers little about his personal politics. He has stated elsewhere that he is not a conservative. Readers of this book, however, will almost certainly be disproportionately conservative and majority white. From an author’s perspective, the demographics of readers are not the primary concern; writers are happy to sell books to readers from any background. I hope the book enjoys success. Nonetheless, I do wonder if this book’s primary audience could benefit from a similar argument, framed somewhat differently.

In a moving passage, Hughes states, “When I look at the current racial landscape of American society, I feel sick at heart. I dread the possibility of black identity becoming tied to a rehearsed sense of victimhood, and of people of color never allowing themselves to participate fully in the privileges of freedom.” I fear many white conservative readers will nod along to these words, without considering whether many on their own side need to hear a similar message.

I am not an alarmist about the state of the country, or the American right more specifically. I reject the argument that there has been a mass radicalization of Republican voters, for example. I nonetheless see concerning trends among conservatives. Much of the online right in particular has clearly embraced its own version of the victimhood mentality. So many popular accounts on X (formerly Twitter) do nothing but serve, all day long, content designed to stoke outrage and a sense of resentment among conservatives.

The right has too many content creators scouring the country for examples of anti-white hatred and discrimination, violent crime in our inner cities, and people promoting bizarre sexual behavior. To be clear, there are perfectly legitimate discussions worth having about affirmative action, criminal justice, and how (if at all) young people should be exposed to different forms of sexual expression. However, too much right-wing media encourages people to wallow in grievance politics. The tendency among some to look to foreign regimes such as Viktor Orbán’s Hungary or Vladimir Putin’s Russia for inspiration is especially insidious.

I should not downplay the very real hardships, injustices, and tragedies many individuals face in America today, and I realize national statistics will bring hurting people little comfort. If we decide it is worth looking at the data, however, we will find that the dystopian landscape many conservative influencers describe does not match reality. A more honest look at the state of America reveals that the country is not a hellhole, for white people or anyone else.

Like all conservatives and classical liberals, I have many complaints about the left, and I reject the direction progressives want to take the country. Some sense of perspective is nonetheless necessary. For most ordinary people, of all races and religions, there has never been a better place to live than the United States, and no better time to live here than now. People from all backgrounds, all over the world, remain eager to come here, which suggests our system continues to work very well.

The fact that some public libraries have hosted “drag queen story hours,” left-wing academics often promote divisive ideas disconnected from reality, and crime rates remain stubbornly high in too many places does not change this. Even if I am wrong in my optimistic assessment about the state of our country, I see little evidence that right-wing grievance politics represent a viable solution to our problems. Hughes fairly accuses neoracists of stoking “endless ideological war.” I fear many of their opponents on the right seek to do the same.

I hope The End of Race Politics finds a large audience, and that it starts many worthwhile conversations. I additionally hope that sympathetic readers will not just use Hughes’ work as a cudgel against the left, but will instead engage in some self-reflection of their own. We should recognize that Hughes makes a broader point that we could all benefit from considering. We will not move closer toward Hughes’ colorblind ideal unless more people across our racial, ideological, and partisan divides are willing to set aside their resentments, giving up the unwholesome pleasures that the victimhood mentality can provide.

Photo by National Park Service — Flickr