One of the best parts of the higher ed portion of the reconciliation bill being pushed in the House of Representatives is a shift from cost of attendance (COA) to median cost of attendance (MCOA).

What is the Cost of Attendance and Why Does It Matter?

COA is the total cost of attending college, including tuition and room and board, but also less obvious expenses like transportation, dependent care, and study abroad costs. Each college sets its own COA. COA is important for two reasons—it provides an estimate of how much money students will need to attend a particular college, and it also factors into how the government determines eligibility for federal financial aid. Maximum federal financial aid is equal to COA minus the government’s estimate of how much a family can afford to pay (formerly the Expected Family Contribution, now called the Student Aid Index).

Benefits of changing to the median cost of attendance

The direct link between a college’s COA and federal aid eligibility leads to a number of problems that could be mitigated by using the median cost of attendance. MCOA takes the COA among all colleges and then finds the median. Aid eligibility for all students is then determined using MCOA rather than each individual college’s COA. Technically, this is done at the credential and academic field level—e.g., a bachelor’s degree in business would have a different MCOA than the master’s degree in anthropology but the mechanics of finding the MCOA are identical. As I described in a 2019 paper, this would have several benefits.

To begin with, it would improve accountability. For example, under the current system, “an inefficient college that wastes money can simply raise its cost of attendance to cover the higher costs, automatically giving its students access to more aid.” However, under the MCOA, this would no longer be the case because raising tuition doesn’t automatically lead to more aid for its students. This would begin to hold colleges accountable when they are inefficient.

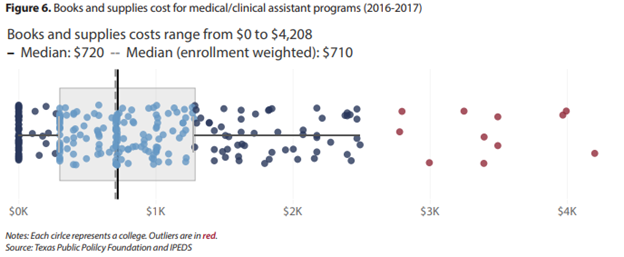

MCOA would also lead to better cost control by colleges. For example, many colleges have let textbook costs climb to obscene levels. Consider the books and supplies component of the COA for medical/clinical assistant programs shown in the reproduced figure below. These costs range from $0 to more than $4,000. Does the college with $4,000 books and supplies costs suffer any ill effects? Not under COA, since that just means their students get $4,000 more in aid. But under MCOA, extravagant textbook costs don’t simply add on to the student’s aid; they displace aid available for other expenses, like tuition.

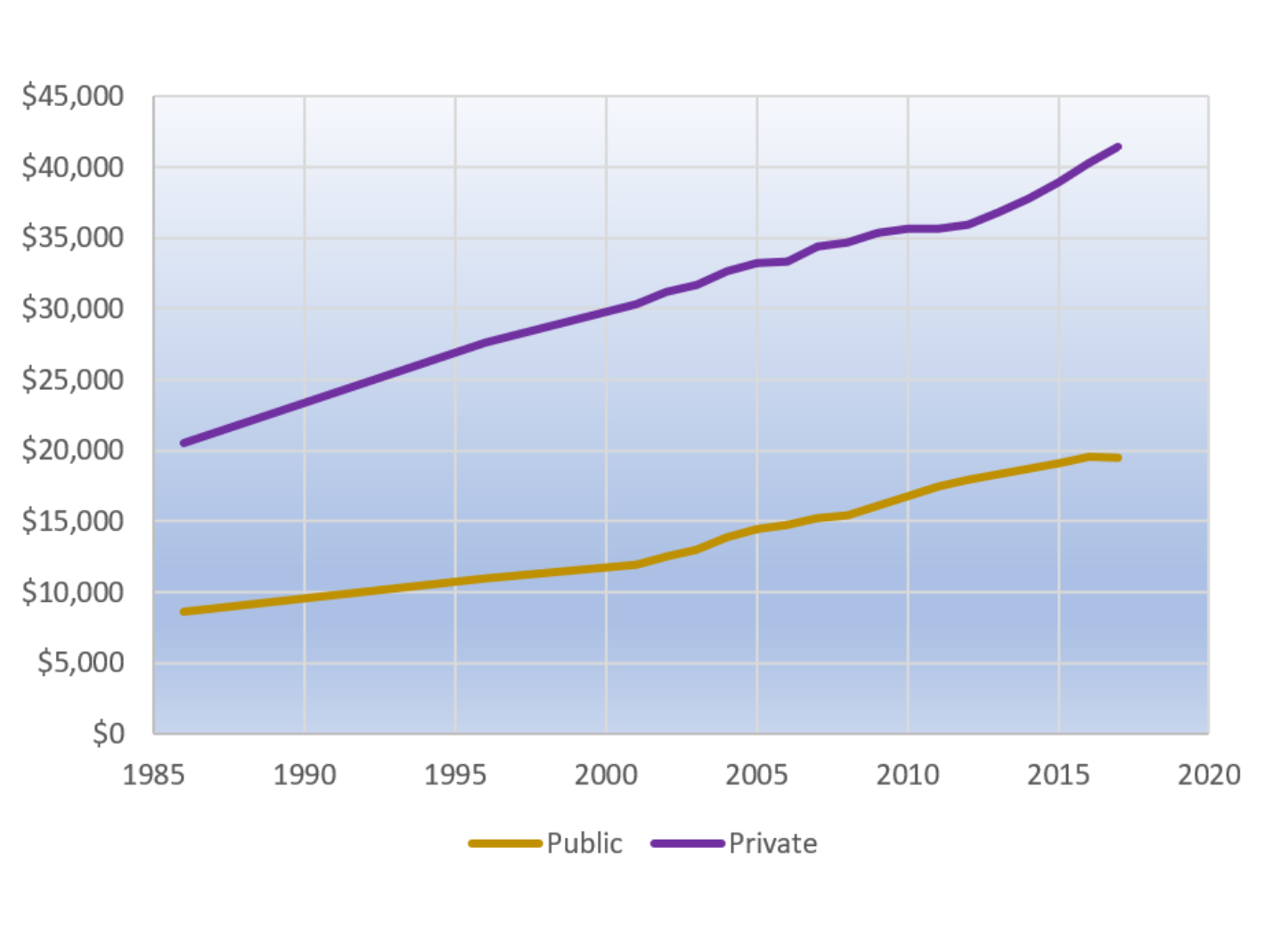

MCOA would also neutralize the Bennett Hypothesis, the idea that the availability of financial aid causes colleges to raise tuition. High-quality studies usually find that the Bennett Hypothesis is real—that colleges tend to raise tuition to exploit students’ access to financial aid. But this undesirable behavior is not a law of nature written in stone; it is driven by bad policy design. The primary driver of the Bennett Hypothesis is that a tuition increase automatically leads to more aid. But when eligibility is determined by MCOA rather than COA, the link between higher tuition and more aid for students is severed, which would neutralize the Bennett Hypothesis since colleges could no longer harvest financial aid funding by strategically setting tuition.

There are a few other benefits of moving to the MCOA, as detailed in my paper, but I want to address some recent objections to MCOA.

[RELATED: Trump’s Cuts Are Exposing Academia’s Biggest Myth]

Rebutting critiques of changing to the median cost of attendance

MCOA has mostly flown under the radar given how many big changes are happening in Washington DC right now. But writing for New America, Rachel Fishman does raise a few objections to MCOA. Her critiques can be grouped into four buckets.

Objections that are wrong

Two of Fishman’s objections are either wrong or overstated. The first is a worry about whether the Department can handle making the calculations:

a functioning Education Department is needed to execute it. And President Donald Trump just gutted it, leaving just three employees in the office that would establish the MCOA, the National Center for Education Statistics.

This is a bit ridiculous. If 3 employees working in a statistical office can’t figure out how to find a median, then we’ve got bigger problems. For writers this would be the equivalent of worrying that after recent layoffs, journalists at the Washington Post won’t be able find the exclamation point on their keyboards. Finding a median is trivial for anyone with some experience working with data. Indeed, just one line of R code would get you all of the MCOA by credential and field of study: “data %>% group_by(fieldofstudy, credential) %>% summarize(medianCOA = median(COA)).”

Fishman also worries that MCOA would cause colleges to increase tuition:

Republicans assume that the policy will make institutions cut costs. But institutions could artificially inflate their COAs in shorter-term credentials, for example, to boost borrowing limits and suck up those dollars.

This is wrong for a subtle reason. As I noted in the study

the price effects are likely to be asymmetric—high-cost programs could be incentivized to lower their tuition and fees, but it is less likely that low-cost programs will be incentivized to raise their tuition and fees. The reason for the asymmetry is that the median cost of college adds a constraint for high-cost programs—they can no longer count on higher aid eligibility for their students. In contrast, low-cost programs face no new constraints or options. For low-cost programs, under both the current system and the median cost of college method, they could raise tuition and have some of the consequences partially offset by aid. So while their students may actually be eligible for higher aid amounts under the median cost of college, other factors that drove these programs to keep their tuition relatively low would still be in effect, so it is unlikely these programs would respond to the new system by raising tuition.

Objections that are not unique to MCOA

There are also some objections that are legitimate, but that aren’t much different under MCOA or COA. For example, Fishman asks “What happens if a student exhausts all of their aid in the middle of their academic program?” While this could be a problem, it is a problem under both COA and MCOA. And in both cases, the primary driver would be loan limits as opposed to COA vs. MCOA.

[RELATED: Higher Education Reforms Could Finance Half a Trillion Dollars in a Reconciliation Bill]

Objections that are unique to MCOA and good

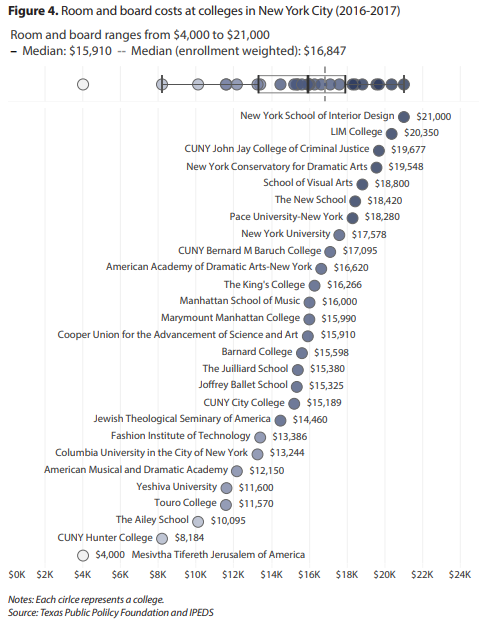

There are some objections that are unique to MCOA, are portrayed as a bug, but that are really a feature. For example, Fishman argues that “colleges calculate cost of attendance in wildly different ways, and that living costs vary widely depending on city, state, or region of the college.”

Calculating COA in “wildly different ways” and then passing the cost along to taxpayers is not a good outcome. Consider room and board costs for colleges in New York city, which range from a low of $4,000 to a high of $21,000 as shown in the (reproduced) figure below. MCOA would replace this vast disparity with a uniform amount around $16,000, a must more egalitarian approach.

But what about differences in costs between cities or states? Costs indeed vary, but it is not true that that is a good reason to provide more subsidies to high-cost areas. For example, it costs a lot more to grow oranges in Alaska than in Florida. The appropriate response to this is to stop trying to grow oranges in Alaska, rather than arguing that it means we should increase subsidies for orange growing in Alaska. If being in New York City provides educational benefits that justify the additional cost, that’s great. But those extra costs are real, and they should be paid by those receiving the benefits, not college students in Nebraska.

Objections that are unique to MCOA and bad

There are also some objections that are unique to MCOA and are probably bad. For example, Fishman asks about “students who transfer mid-year between programs with different median costs.” The COA method doesn’t need to worry about this because COA is set at the credential level, but MCOA, which is set by credential and academic field, does need to deal with this. The easiest way of addressing this would be to mimic how the current COA system handles students who transition between credential levels.

Overall, switching from the cost of attendance to the median cost of attendance would be beneficial, and I certainly hope to see their provision survive the reconciliation bill process.

Follow Andrew Gillen on X.

Image: “Median tuition, public and private schools” by Stilfehler on Wikimedia Commons

Good Information

Regards, PTS Terbaik

How does shifting from the Cost of Attendance (COA) to the Median Cost of Attendance (MCOA) improve accountability and cost control in higher education? https://bte.telkomuniversity.ac.id/pengenalan-internet-of-things-iot-dalam-telekomunikasi/

Simple — it shifts financial aid from paying a percentage of cost to percentage of average price to a percentage of average cost regardless of what your actual cost is.

Let me give some hypotheticals, keeping the math simple:

You are accepted at three schools, which charge the following a year:

Dreary Cunderblock School — $100

Flagship State University — $200

Fancy Private School — $300

The way it currently works, you are going to pay the first $100 regardless, with FinAid paying the rest — the incentive is for you to go to the fancy school because it has nicer buildings and won’t cost you any more than Cinderblock U.

This is why we currently have the amenities arms race — colleges and universities building ornate (and quite expensive) campi to attract students who aren’t the ones paying for it,

Now let’s change to the situation where you get the *average* cost — $200 — in financial aid. Your costs would now be:

Cinderblock U — $0

Flagship Univ — $0

Fancy Private — $100

And then let’s say that your $200 in FinAid was broken down to be the first $100 in Pell Grant and the second $100 in loans — that wouldn’t be forgiven. Hence your costs (now/total) would be as follows:

Cinderblock U — $0/$0

Flagship Univ — $0/$100*

Fancy Private — $100/$200*

*In both cases, the $100 in loan will wind up being $200 with interest included.

Hence if you decide to go to the fancy private university with the lazy river ride on the roof and the rest, it’s going to cost you $100 now and you’ll have another $100 in loans to repay later — but if you go to Cinderblock U, you won’t have any loans at all.

The incentive is to go to the cheaper school, which then forces schools to compete on price.

There is one thing that will need to be addressed — the discrepancy between the off campus housing and dormitory costs at IHEs that have a significant fraction of their students living in the local community.

What some universities do is artificially deflate the costs of living off-campus which does three things.

First, it allows them to increase the costs of the dorms (money they get) without increasing their average cost of housing because they are claiming that the students who are living off-campus are paying less than they actually are.

Second, it serves to incentivize students to purchase a lower quality/less desirable dormitory bed than off campus housing. This is particularly true in terms of non-cash value, i.e. the ability to avoid the politicized purgatory that the dorms often are.

Third, it victimizes applicants unfamiliar with the area who rely on the university’s figures and budget their off-campus housing costs on these false figures.

The solution is simple: Use HUD’s Section 8 “Rent Reasonableness” figures which are published by the local housing authority and have to be in some HUD database somewhere. Hence either pull the data from there, or ask each IHE to quote the local HA figure.

Instead of Oranges in Alaska, the better analogy would be Bobsled teams at UCLA or Baseball at U-Alaska, Fairbanks where the snow doesn’t melt until late April, with fields muddy after that. Yes, if you spent enough money, you could build (and heat/cool) an indoor stadium to play the sport independent of season, as the Toronto Blue Jays did — but it costs lots of lots of money, and it’s far cheaper to play baseball in warmer locales.

Forcing colleges to use honest off campus housing costs would direct college students to areas with lower-cost housing, which are usually areas with chronic high employment.