The Continental Congress appointed George Washington Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army on June 19, 1775. Washington did not think he was qualified for the job. It’s not like any other part of the Patriot resistance was ready for war.

Washington was off to lead a bunch of Massachusetts farmers who trained part-time. There were a lot of them, and they’d beaten the over-confident British at Lexington and Concord, but they weren’t much better than a rabble in arms. And there was no way to be certain they wouldn’t slouch back to their fields whenever it pleased them.

Congress authorized a new Continental Army along with commissioning Washington. That would be a few hundred riflemen from Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. They might be sharpshooters, but there weren’t many of them.

[RELATED: Before the Flag, the Fight]

Not that Congress could pay for a vast army. It authorized spending two million dollars, backed by their IOU. Washington had Congress’ commission, a store of funny money, and marksmen and militia he maybe could make an army of. He need not have dwelled on his own shortcomings as a leader.

His modesty was indeed a good reason to make him general. But Congress had other good reasons as well.

Washington hadn’t just been an officer in the French and Indian War. He’d been an officer of the Virginia Regiment, recruited hastily from the usual riffraff from 16 to 60, as well as more public-spirited volunteers. But Washington’s experience leading and training a motley of raw soldiers was especially useful as he headed to take command of the militia besieging Boston.

Then, too, Washington’s personal wealth was an extraordinary boon to the war effort. Washington said he would serve for no salary, merely asking for reimbursement for his expenses. But “reimbursement” actually was another gift from Washington to the Continental Congress—he paid out of pocket, to be reimbursed at a later point by Congress. Washington’s expenses in his first month included the first payments to set up America’s espionage network behind British lines. Washington, perhaps the wealthiest man in America, probably had better credit than Congress. Congress was literally in debt to Washington for his military services throughout the War of Independence.

Washington himself remarked that he was a politically useful appointee. This is true—a Virginian, a representative of the largest and richest colony, was a sensible political choice. It also eliminated squabbles about military merit: other would-be commanders-in-chief could comfort themselves that Washington owed his position to politics. Of course, this meant that Washington still would need to prove himself as a general—but that would have been true of his rivals as well.

Washington’s excellent character impressed all his fellow delegates to the Continental Congress. He looked a general. He did have as much military experience as anyone in America. But Congress ultimately had to gamble that he would grow in the job. Thank heavens the gamble worked out.

[RELATED: One Hill Sold, a Revolution Gained]

The billionaire Trump has some parallels to Washington. Certainly it helps that he had deep enough pockets to resist persecutors lawfare by his opponents. But I think the truer heirs to Washington are all the recruits to his administration.

These, after all, are the outsiders who never have been part of the bipartisan establishment. They are not raw recruits—those are the MAGA millions—but they are outsiders, colonial officers never allowed to command British regulars, sometimes wealthy men who stake their private riches for the nation’s good. By their thousands, they are ready to serve weary years, often far from home.

We have many Washingtons in Washington. Some also need to grow in their jobs. I think they will.

Follow David Randall on X, and for more articles on the American Revolution, see our series here.

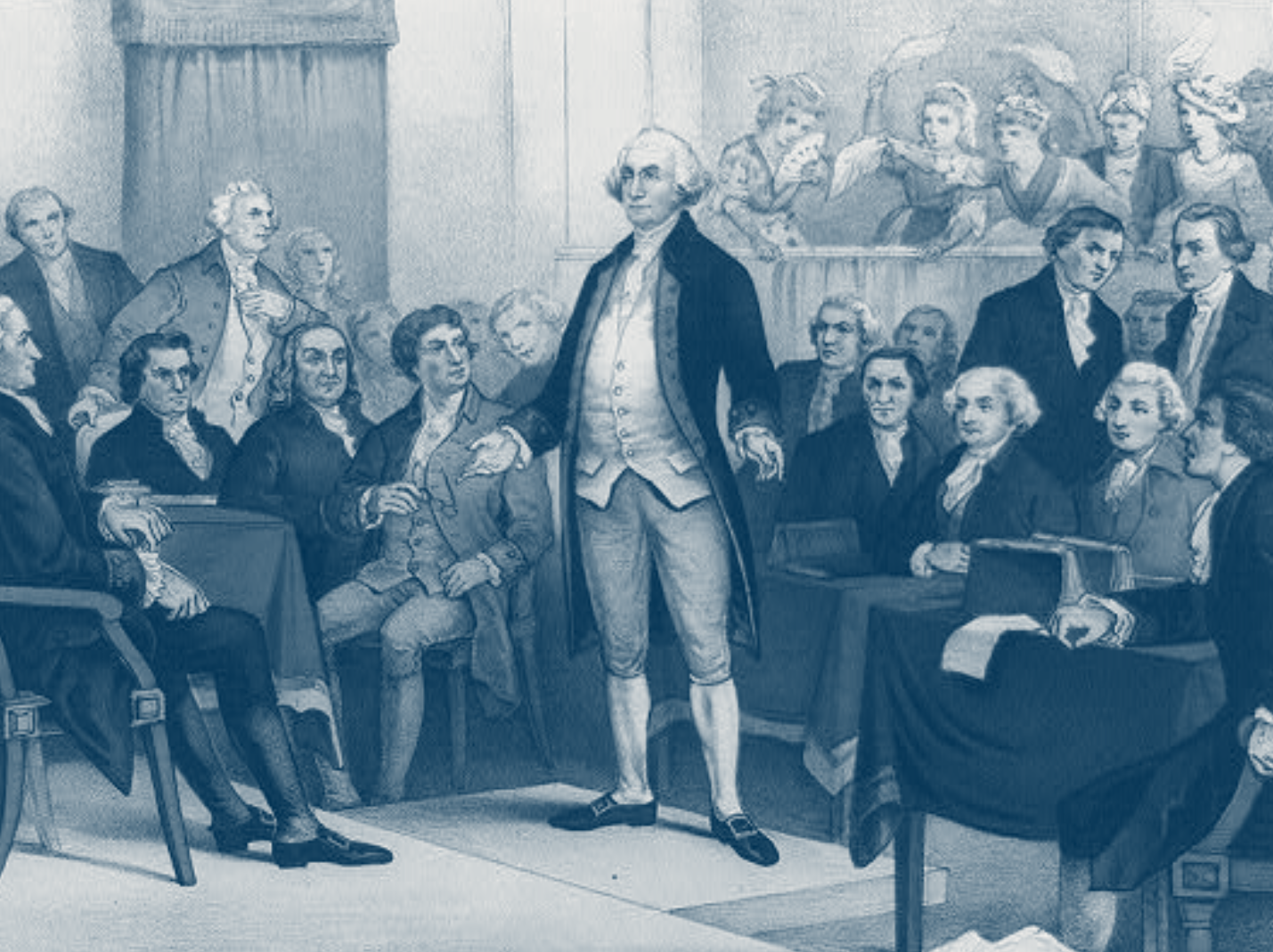

Image: “Washington, appointed Commander in Chief” by Currier & Ives on Picryl

“Washington hadn’t just been an officer in the French and Indian War. He’d been an officer of the Virginia Regiment, recruited hastily from the usual riffraff from 16 to 60, as well as more public-spirited volunteers. But Washington’s experience leading and training a motley of raw soldiers was especially useful as he headed to take command of the militia besieging Boston.”

Ummm…. This is outside my area of expertise but weren’t there some serious questions asked about Washington’s service in the French & Indian war, including the allegation that he actually started it with the Battle of Jumonville Glen? And then Washington and his unit getting captured by the French Canadians?

Again, I don’t know all the details but I have heard that Washington really wasn’t that good a military commander during the French and Indian War. By contrast, the New England “rabble in arms” (who weren’t just from Massachusetts) did pretty well at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Lexington and Concord were a cluster-bleep by quite overconfident British forces, and then the Americans adopted “sniper” tactics that were not part of European warfare. But Bunker Hill was classic European tactics on both sides.

Four days from the shortest night of the year, in Boston there is only about seven hours of actual darkness which limited how much of a redoubt they could build before first light which came about 4:30 AM. They successfully repelled the first two British attacks and would have held the position if they hadn’t run out of ammo. And even then, they successfully evacuated the position with only 30 being captured, 20 of whom were so seriously wounded that they subsequently died.

That’s pretty damn good — and while Joseph Warren died there, they still had Joseph Prescott and Israel Putnam, capable commanders. And as to “sharpshooters”, they’d done pretty well with the British retreating through Arlington.

IMHO, Washington’s strengths lay in diplomacy, not military tactics. Like Eisenhower during WWII, Washington more kept his generals from fighting with each other than anything else. Dealing with Congress, dealing with 13 different sovereigns, bringing in foreign support and creating a national army, those were diplomatic victories.