Miseducation and the Law in America, Part I

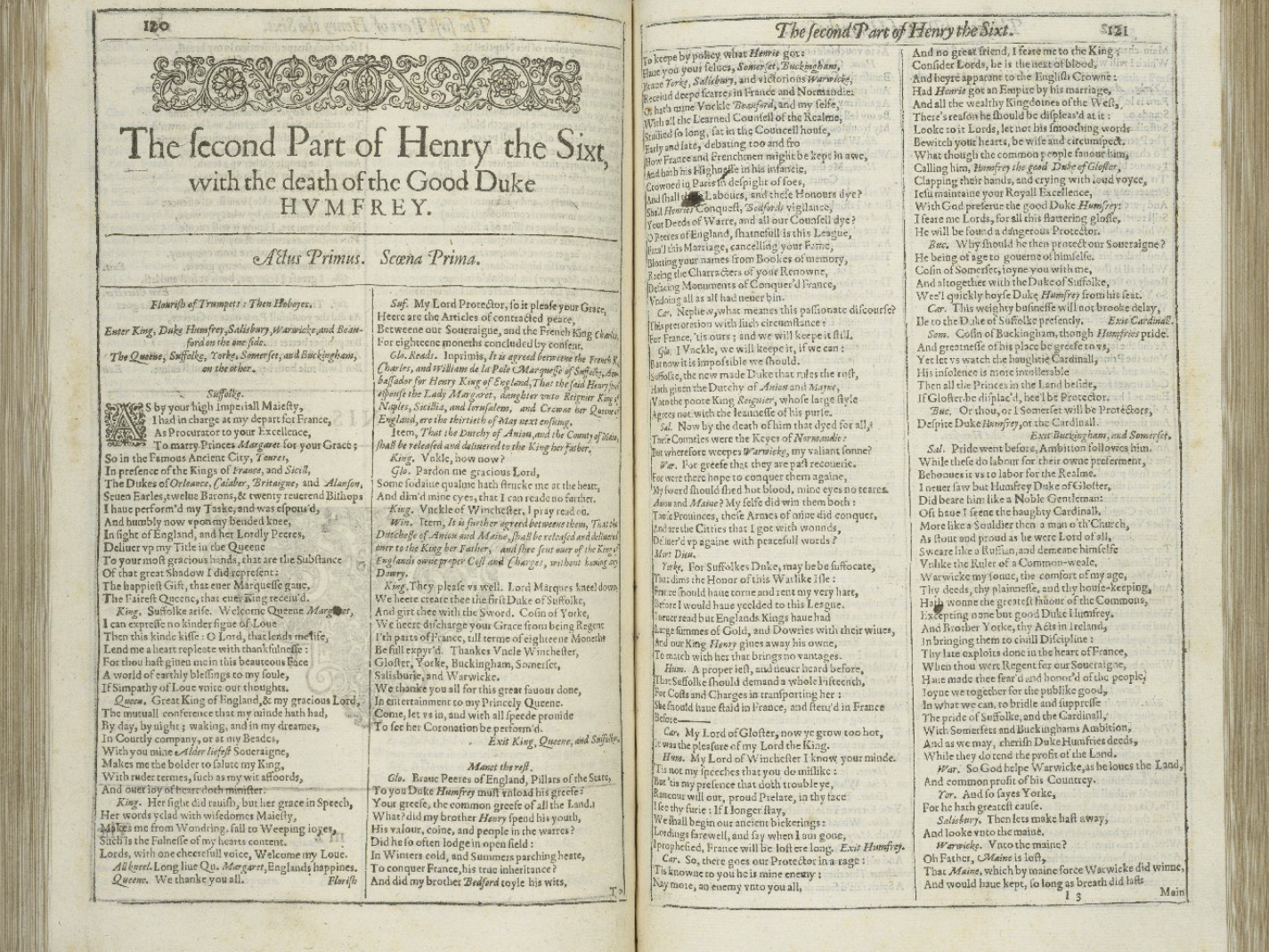

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.”

– Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 2, Act 4, Scene 2

America is litigious. Many will roll our eyes at the thought of the creatures that make it that way. Jokes learned in childhood deprecate them in titanic fashion: “What do you call 100 lawyers at the bottom of the ocean?” Answer: “A good start.” This may not seem so funny in 2022. On the bright side, we’re still a long way from killing all of them.

Near the end of volume one of Democracy in America (1835), in an ominous chapter—“What Moderates the Tyranny of the Majority in the United States” (1.2.8)—Alexis de Tocqueville claims that a free society emerges from its legal profession. A transduced aristocracy of lawyers assumes the role of opposing majority rule. Searching for civil society’s new saviors, the French count and magistrate projects himself onto men like Jay, Hamilton, Madison, and Jefferson:

The lawyer belongs to the people out of self-interest and birth but to the aristocracy by customs and tastes; he is virtually the natural liaison officer between these two and the link which unites them.

In all free governments, whatever their make-up, lawyers will appear in the leading ranks of all parties … This same observation is true of the aristocracy. … I am saying that in a society where lawyers unquestionably hold the high rank which naturally belongs to them, their attitude will be dominantly conservative and will prove antidemocratic.

In addition to harboring repugnance for lawyers, most Americans recoil from anything deemed “antidemocratic” or “aristocratic.” If we weren’t the focus of Tocqueville’s most important book, we’d rank among those least likely to appreciate it. This can be remedied by studying him in the context of (1) Shakespeare, (2) history, and (3) the U.S. Constitution.

“Kill all the lawyers” is Dick the Butcher’s call for regime change. Tocqueville is even more precise than Shakespeare: “All sovereigns who have wished to draw the sources of their power from themselves and to control society instead of letting it control them, have destroyed or weakened the jury system. The Tudors used to imprison jurors who decided not to convict and Napoleon had them chosen by his agents.” But unlike Shakespeare’s Dick, Tocqueville advises against attacking a legal system, especially if majority rule is at hand:

The prince who sought, in the face of an encroaching democracy, to destroy the power of the judges in his states and to lessen the political influence of lawyers would be committing a great mistake. He would let go the substance of power to lay his hands on merely its shadow. I am quite clear that he would find it better to bring the lawyers into the government. Having entrusted to them a violently achieved despotism, he might have received it back from them looking like justice and law.

History also clarifies Tocqueville’s concerns. The French Revolution spawned Napoleon, who left 3.25 to 6.5 million dead after sacking Europe’s Ancien Régime in 1803–15. Given the carnage, and given Tocqueville’s precarious status as landed gentry and jurist at Versailles, we might tolerate his attribution of a certain nobility to the law. Revolutions can spread freedom but they often collect heads in the process.

[Related: “How to Be of Two (or Three) Minds About Critical Race Theory”]

We also see how majority rule can go wrong reflected in those American political structures that guard against majorities who want both the right to enact laws and the right to break them. For Tocqueville, the legal caste’s mediation echoes the U.S. Constitution. Which brings us to a monstrous, paradoxical truth: antidemocratic bodies and institutions are needed to save democracy from itself. America applies Montesquieu’s idea of divided government as a preventive, a kind of social temperance: “suppose you had a legislative body composed in such a way that it represented the majority without necessarily being the slave of its passions, or an executive authority with its own independent strength, or a judiciary independent of the other two, you would still have a democratic government but with hardly any risk of tyranny.” And the legal class assists the operation: “When the American people become intoxicated by their enthusiasms or carried away by their ideas, lawyers apply an almost invisible brake to slow down and halt them. Their aristocratic leanings are secretly opposed to the instincts of democracy.”

Ultimately, Tocqueville is making an institutional argument, albeit a big one that reads as might a Möbius strip. The democratic society from which it emerges functions in real time thanks to its own spontaneously evolving legal framework:

Lawyers in the United States constitute a power which is little feared and hardly noticed; it carries no banner of its own and adapts flexibly to the demands of the time, flowing along unresistingly with all the movements of society. Nevertheless, it wraps itself around society as a whole, is felt in all social classes, constantly continues to work in secret upon them without their knowing until it has shaped them to its own desires.

A particular type of personality emerges too: “Men who have made the law their special study have learned habits of orderliness from this legal work, a certain taste for formalities, a sort of instinctive love for a logical sequence of ideas, all of which make them naturally opposed to the revolutionary turn of mind and the ill-considered passions of democracy.” By allowing reason to outwit emotion, a legal system salvages freedom from radical egalitarianism. And like the Framers and senators (not representatives), Tocqueville saw the many tortured, mixed, and divided aspects of American government as “a potent barrier against the excesses of democracy.”

That a healthy society should fight for its legal system owes to their imperfections. A perfect legal system would be as ominous as a perfect society; nobody would fight for anything or we would all fight constantly for everything. A major story from the Revolutionary Era is John Adams’s defense of British soldiers and their commander in a Boston courtroom. It signals that Americans are ready for self-governance. Yet, in 1798 Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts, not exactly models of legislation. The War of Independence was all about bad laws (taxes without representation, obligation to house troops, etc.). The Civil War was fought over even graver legal matters; the North imposed the idea that blacks were not property and had the same rights as other citizens. After the war, constitutional amendments enshrined the idea. Tocqueville notes at one point that the Framers—35 of whom studied law, including Adams, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, and Jay1—were more respected than loved. Perhaps only a well-considered crisis lays the proper grounds for a nation to move forward.

We expect negative checks on democracy’s excesses from an aristocratic lawyer. But Tocqueville’s final argument views his profession as a social good that can contribute positively to democratic freedom. In a deeply utilitarian sense, liberal democracy works its magic foremost as a pedagogical exercise centered on juries: we learn about republican democracy through “citizens chosen randomly and entrusted temporarily with the right to judge.” A jury system is republican in logic and process; the sovereignty of the people is affirmed according to a specific voting pattern and all manner of advice of counsel, much of it contradictory and dishonest.

[Related: “A Tribute to History’s Thinking Men of Action”]

Tocqueville often discloses the darker side of what many consider the heroic aspects of America, or else he finds a secret happy melody in an otherwise horrific symphony. Here, his best defense of the democratic legal order has little to say about its ability to resolve cases. Thinking juries are an instrument for determining guilt or innocence misses the forest for its trees. No, what juries do is disseminate republican principles among an otherwise dangerously democratic people.

Anglophone people have established a range of political systems—monarchy in England and republics overseas—but they have “uniformly advocated the jury system.” Tocqueville explains the significance of this:

A judicial institution which has thus commanded the approval of a great nation over centuries and has been copied enthusiastically in every stage of civilization, in every climate and under every form of government, cannot possibly be contrary to the spirit of justice.

The jury is, therefore, first and foremost, a political institution and must always be judged from that point of view.

A jury is the ultimate campus at which we learn our own political science: “it tends to establish magistrates’ influence and to spread legalistic attitudes.”

A jury offers experiential learning about how republican government works and why. Our society rests first on the principle that someone is not guilty just because some majority says so. This antidemocratic reasoning grounds the right to a trial by jury. No mob of Bostonians wanting to lynch British soldiers, no mob of white Southerners wanting to lynch a black man, not even a mob of theologians wanting to lynch Judas can be allowed to proceed. As Madison put it: “Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob” (Federalist 55). Moreover, the right to trial supposes the presumption of innocence. The accused never carries the burden of proof in America, and in serious cases one juror out of twelve can acquit someone. Otherwise, no evidence would be needed, and a judge or a simple majority of jurors would convict, in which case justice would reflect too much the opinion of the powerful, i.e., tyrants and mobs. By colonizing juries with rules and the presumption of innocence, we are just as Tocqueville saw us: a supremely antidemocratic people.

1 Brown, Richard D. “The Founding Fathers of 1776 and 1787: A Collective View.” William and Mary Quarterly, 3.33.3 (1976): 465–80.

Image: Folger Shakespeare Library, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.