“What Is Replacing DEI? Racism” is the title of a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education by Arizona State University professor Richard Amesbury. It is provocative, for sure, but also comes across as ignorant since racism is to many people a feature of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) itself. How can abolishing DEI be racist if DEI is itself racist?

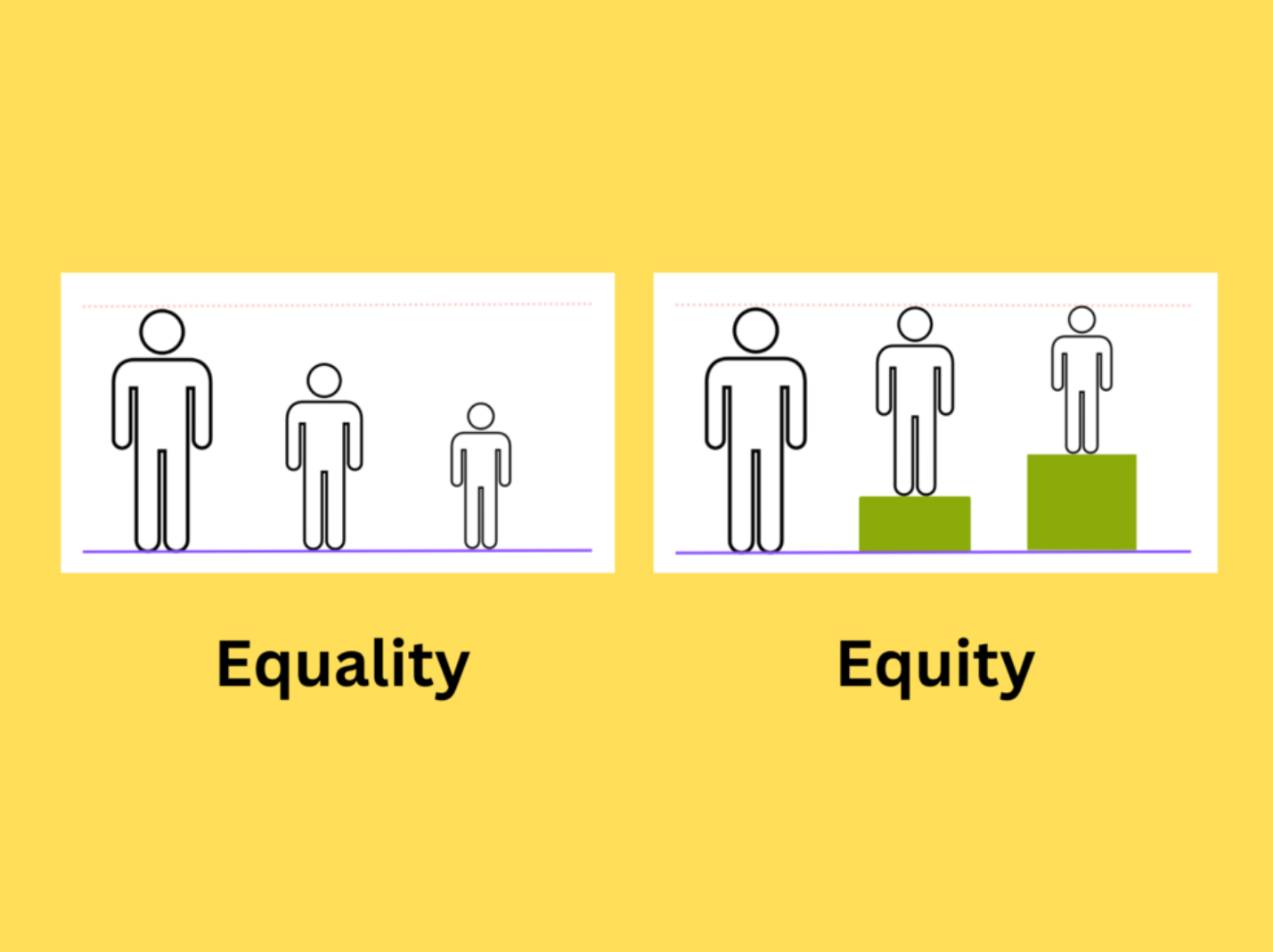

After all, DEI demands equity—equal outcomes. Equity refers not just to individuals but to averages. So, equality of outcomes is demanded from a human population that is enormously variable in its interests and abilities. Given the existence of immutable group—think racial—differences, equity can only be achieved by treating people differently, such as through racial discrimination. DEI is, therefore, intrinsically racist.

All groups are not equal, physically or mentally, which Amesbury sees “as something to be overcome … With such a view, there can be no compromise.” Really? Are short people to be stretched, brunettes to be bleached, and the smart forced to view the world through the wrong end of a telescope?

Nonsense, of course, and this real diversity is the reason the law favors colorblindness: an applicant “must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race,” as Supreme Court Justice John Roberts, quoted by Amesbury, has said. “Students are to be treated as ‘individuals’ and not on the basis of race,” he adds. Yup, sure doesn’t sound racist to me.

Yet, somehow, it is according to Amesbury.

[RELATED: Just Say No to Discrimination]

What is “racial”?

Amesbury offers standardized testing (ST) as an example. There are pressures to eliminate ST because some identifiable groups do worse than others. Amesbury claims that the Trump administration appears to consider such actions as racially motivated if their purpose is “to achieve racial balance or to increase racial diversity.” Well, if your intention is to “achieve racial balance,” then yes, you are indeed “racially motivated.”

And yes, the administration’s “Dear Colleague” letter does reject “the goal of racial proportionality.” As well it should, because “racial proportionality” is not to be expected even in a totally fair, merit-biased society. People differ in all sorts of ways, which our author terms “a normative conception of racial inequality.” More simply stated: groups differ. It’s a fact, not a “normative conception.” If groups differ, indeed even if they don’t, “racial proportionality” is not the default option.

In other words, given the reality of individual and group differences in interests and abilities, the proportional representation of every group in every profession and every walk of life is a total chimera. It is nonsense that could only be achieved by extremely undemocratic means.

Race

Amesbury targets controversial law Professor Amy Wax, who has been punished by her university for her comments. I have read many of them, and it is clear that Wax suffers from a defect not shared with her critics. She speaks clearly. She is sometimes blunt.

Here are a couple of quotes from Professor Wax:

Take Penn Law School, or some top 10 law school … Here’s a very inconvenient fact … I don’t think I’ve ever seen a black student graduate in the top quarter of the class, and rarely, rarely in the top half … I can think of one or two students who scored in the top half in my required first-year course.

And another:

We know that—and I’ll just come right out and say it—on average blacks have lower cognitive ability than whites. That’s just a fact.

[RELATED: Maryland Regrets the End of Racial Discrimination]

These comments say nothing about race, either as a genetic property or a social construct. Wax is referring to a self-identified group that, as a group, scores lower on standardized objective tests. The “innateness” of these differences is not only almost impossible to measure, but it is also totally irrelevant. Differences exist. They may, in the long run, be remediable through improved education and so on. But they are a fact now, and they are correlated with social outcomes. Amesbury acknowledges the reality of disparities, writing:

[T]hat racial disparities should be understood not as injustices to be rectified but as reflective of differences of average ability among people of different racial groups—is, I believe, the key to understanding much of today’s opposition to the values of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

But all the evidence is that these differences are not “injustices to be rectified” but largely reflect real individual differences in interests and abilities, a possibility dismissed by Amesbury. For him, it is all about achieving a society where all are equal:

This opposition is not a good-faith contribution to the debate over how most effectively to bring about an equitable society. It is not the claim of the Roberts Court that a “color-blind society”—one in which racial differences do not correlate with differences of education, wealth, or health—can best be achieved by means of “color blind” methods. Rather, it is a repudiation of that very goal.

He goes on to say:

[Supreme Court Justice] Roberts’s view is that equal opportunity will result in an equitable society. Wax’s argument is that it will result in a racially stratified one. Roberts’s view is ahistorical and naïve. Wax’s is repellent.

Amesbury misrepresents Robert’s view. His aim is not equity but justice, which is quite proper for a Supreme Court justice. It is not that equal opportunity will result in an equitable society, but that equal opportunity is a characteristic of a just society. Only if inequality is the supreme evil—or can be ignored—can it be weighted above justice.

Amesbury seems to believe either of two things:

- People really do not differ: racial disparities are “injustices to be rectified.” So, in a really fair society, there will be no social differences between different groups, or

- Even if people do differ, steps must be taken to ensure that all groups end up the same.

Point 1 is false, so point 2 must be Amesbury’s position. For Amesbury, equality of outcome—equity—is the supreme value, no matter that achieving it will entail many ills, from injustice and coercion to the elevation of mediocrity over excellence.

Equity, the equalitarian imperative, is what is really “repellent.”

Image: “Equality vs Equity” by Ciell on Wikimedia Commons

My holograms for racist, racism, and racial:

Radicals/ Reprobates Against Citizens Interacting Sanely & Truthfully/ Maturely

Radicals/ Reprobates Against Citizens Interacting Amicably/ Analytically & Logically

Imagine the outcry that a 20% limit on Black athletes would cause….

An excellent rejoinder to Amesbury! His advocacy of governmentally-enforced “equity” among groups is one of those luxury beliefs that appeal to cloistered intellectuals who will never feel any of the adverse consequences of the policies they demand.