The reconciliation bill is shaping up to be the boldest legislative change in higher education in decades. But it is still in an early stage, with the House having passed its version, and the Senate hoping to do so soon. Next will come negotiation to work out any differences between the House and Senate versions, which will also have to pass in both. Here’s where things stand on various topics, with my thoughts on what a reasonable compromise would look like in the final bill.

Pell Grants

Both the House and Senate bills make some minor changes to eligibility for Pell Grants. But the biggest change is to expand eligibility for Pell Grants to short term programs, often referred to as workforce Pell. The main difference is that the Senate requires the state to approve of each program’s eligibility and requires programs to be aligned with industry-recognized credentials. The House takes a different approach that focuses on outcomes like graduation rates, job placement, and graduates’ earnings relative to the cost of the program. A good compromise would be to merge these approaches. A program could be eligible for workforce Pell if it meets the House’s outcome requirements or if it meets the Senate’s state approval requirements.

Regulatory Relief

Providing regulatory relief is also present in both versions, but there are some large differences. Both the House and Senate seek to revoke Biden’s changes to borrower defense and the closed school discharge, which would be a clear win. The House would also eliminate gainful employment and the 90-10 rule while the Senate leaves those in place. I would urge the Senate should yield to the House on both of these, but especially for gainful employment. The selective targeting leaves wide swathes of higher education free from accountability.

[RELATED: The Senate Can Strengthen Student Loan Accountability—Here’s How]

Student Loans

Some of the biggest changes in the final bill will affect student loans. Both the House and Senate eliminate Grad PLUS loans, which is long overdue. Both would also cap Parent PLUS borrowing, which is essential because many parents are borrowing too much. However, the House and Senate adopted different caps. A good compromise would be the Senate’s aggregate cap—$65k vs. $50k—and the House’s annual cap—cost of attendance less other aid.

The House would eliminate Subsidized loans, while the Senate would not. The Senate should defer to the House on this one. Interest rate subsidies—the only difference between Subsidized and Unsubsidized loans—are a terrible way to go about providing funding for higher education.

Caps on annual or aggregate borrowing are also modified. The House would change the lifetime limit for undergraduate loans to $50k, which is between the current cap of $31k for dependent students and $57.5k for independent students. It would change the limit for all graduate students to $150k. The Senate leaves undergraduate caps unchanged but changes the annual cap for professional degrees to 50k per year, and the annual limit for graduate degrees to $100k and for professional degrees to $200k. A good compromise would be to adopt the Senate’s approach to loan limits for undergraduates—no changes—but to move closer to the House’s approach for graduate students. A lifetime limit of $200k for professional degree students is just too high. If their earnings potential justifies borrowing that much, they should have no problem borrowing in the private sector.

Both versions also phase out the existing income-driven repayment plans and replace them with the Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP). The main features of this plan include a minimum monthly payment of $10, payments of one percent to 10 percent of adjusted gross income based on a sliding scale (e.g., one percent of AGI for borrowers earning between $10k and $20k), and forgiveness of any remaining balance after 30 years of payments. Monthly payments are reduced by $50 per dependent, any unpaid interest is waived, and principal is guaranteed to be reduced by $50 every payment. While I have some reservations about certain provisions, such as waiving unpaid interest, overall, it’s a pretty good plan. An Urban Institute analysis finds that it closely mirrors the REPAYE plan.

Aid Eligibility

Another key difference between the House and Senate versions is that the House adopts the median cost of college method to determine aid eligibility, while the Senate maintains the current cost of attendance method. If the Senate worries about the Bennett Hypothesis at all – the consistent finding that colleges raise tuition when federal aid is available, so as to capture the money for themselves rather than letting students benefit from the aid – then they should adopt the House’s median cost of college idea. The median cost of college is probably the best tool to neutralize the Bennett Hypothesis because it takes away the blank check feature of the current system. Under the current system, for each $1 they raise their price, their students’ loan limit increases by $1. This makes it very easy for colleges to raise prices. But the median cost of college method determines aid based not on the cost of attendance at a particular college but rather the median cost of attendance among all colleges. In practice, this means that high priced colleges get their blank check taken away by the median cost of college method, which is precisely why the Senate should defer to the House on this one.

[RELATED: Median Cost of Attendance is a Great Idea]

Accountability

The biggest difference between the House and Senate versions concerns accountability. The Senate focuses on earnings floors. Programs would lose access to federal aid if their graduates earn below a threshold. Bachelor’s degree program graduates would need to earn more than those with a high school degree, while those with a graduate degree would need to earn more than bachelor’s degree graduates.

In contrast to earnings floors, the House proposes a risk-sharing system under which colleges would be required to reimburse the government for a portion of the government’s losses on loans to their students. The share of losses due is determined by the price the college charges relative to the value-added earnings for its graduates. The House paired this with a new grant funded by the risk sharing payments such that colleges that are low cost or that increase their student’s earnings by a lot would generally benefit from the combination of risk sharing and grants, while colleges that are high cost or don’t prepare their graduates for labor market success would generally have higher risk sharing payments than grants.

The Senate thinks the House’s risk-sharing plan is too complicated, so here’s my proposed compromise.

One, adopt the Senate’s earnings floors. These are a good first step and will weed out some low-performing programs. A couple of tweaks to consider: First, if gainful employment regulations are revoked, add an earnings floor for certificate programs—currently not included in the Senate version because they are already covered by gainful employment. Second, add a safe harbor. There may be programs where graduates don’t earn much, but that don’t impose losses on taxpayers, perhaps because their employer repays their loan. Seminaries could be an example. I would recommend adding a safe harbor based on repayment rates, where programs with repayment rates above the median repayment rate for all programs are still eligible even if their graduates’ earnings are below the floor.

Two, adopt the House’s risk-sharing plan for graduate programs only—and drop the grant program, since without the risk-sharing payments, there is no money for the grant program. Leaving undergraduate programs alone and focusing just on graduate programs has a number of advantages.

First, there aren’t any open-access graduate programs. It’s one thing to hold a highly selective college accountable for bad outcomes, but it’s another to tell an open-access community college that you have to take—nearly—everyone, and then punish them when their outcomes are worse. The House bill dealt with this by introducing new Promise grants that disproportionately went to open-access type colleges, but applying risk sharing just to graduate programs sidesteps the issue completely.

Second, graduate programs are almost exclusively at relatively wealthy colleges that can afford the risk-sharing payments. This helps inoculate the new system from public relations problems. Many would question the appropriateness of charging a struggling open-access community college a risk-sharing payment, whereas few will object to charging a risk-sharing payment to colleges with a billion-dollar endowment.

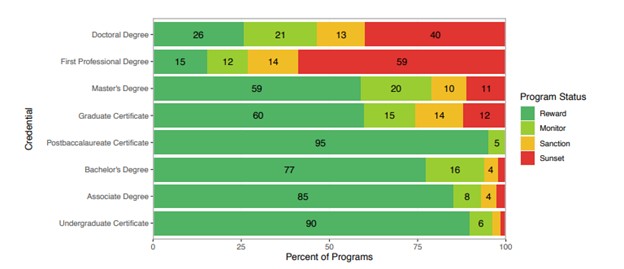

Third, graduate programs have a highly disproportionate share of high-risk and low-reward programs. For example, a study of mine from a few years ago evaluated programs based on their graduates’ debt relative to earnings. A figure from that study uses green to indicate good outcomes—low debt relative to earnings—yellow to indicate worrying outcomes, and red to indicate big problems—high debt relative to earnings. Graduate programs have a lot of yellow and red.

In fact, graduate programs account for almost two-thirds of failing programs, which means that restricting risk-sharing payments to graduate programs would still capture most of the bad programs out there.

Fourth, by applying risk sharing to one segment of higher education, we can assess its consequences before implementing it across the much larger space of undergraduate education.

Overall, these are a host of good ideas in this bill, and I’m excited to see how the bill evolves over the coming weeks and months.

Follow Andrew Gillen on X.

Image of the U.S. Capitol by Elijah Mears on Unsplash

Gainfil employment is meaningless if it is applied as a mean average because a few people with really good pay will skew the average.