Mass student debt forgiveness is unpopular with Republicans and even some Democrats. As such, it’s unlikely that the Biden administration will forgive all $1.45 trillion in student loan debt prior to the midterm elections. But that hasn’t stopped unelected bureaucrats in the administration from working behind closed doors to forgive massive amounts of student loans without congressional authorization.

The administration has forgiven $16 billion in student loan debt since Biden took office. One program the administration has used to quietly forgive debt is the “borrower defense to repayment” program. Borrower defense allows students to receive debt forgiveness for some or all of their federal student loans if they can prove that their universities engaged in fraudulent activity.

The Education Department (ED) will forgive an additional $415 million in student loan debt for graduates of DeVry University, ITT Technical Institute, and Westwood College following an investigation into the for-profit universities’ advertising methods. The investigation found that these institutions used deceptive marketing campaigns to mislead students about their salary and employment potential post-graduation. DeVry, for example, reportedly told prospective students that it had a 90% job placement rate within six months of graduation. In reality, the placement rate for recent graduates was less than 60%. This latest round of debt forgiveness means that, since Biden’s inauguration, the ED will have unilaterally approved at least $2 billion in federal student loan forgiveness through borrower defense alone.

The justification for these actions appears strong at first glance. Indeed, these institutions certainly engaged in deceptive practices. But there’s more to the story. While the ED wants to portray debt forgiveness as a means of delivering justice to defrauded students, in reality, no such justice has been served. The borrower defense program simply enables the ED to shift accountability for fraud from the perpetrators—the institutions themselves—to the taxpayer.

The program serves as only a band-aid solution for the much larger problem of federal subsidization of sham universities. Borrower defense does nothing to hold universities accountable for wrongdoing, and it therefore only increases the incentive for higher education institutions to commit fraud. Meanwhile, taxpayers are on the hook to clean up the mess by constantly bankrolling student loan forgiveness.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Caspar Weinberger, the Health, Education, and Welfare secretary under the Nixon and Ford administrations, first proposed borrower defense in the 1970s. Weinberger’s Office of Education had found concerning patterns of deception by universities—primarily for-profit institutions. Weinberger believed that the government bore some responsibility for the costs because it had effectively endorsed the operations of these universities by supplying federal student loans.

A method for implementing Weinberger’s idea of borrower defense was not put in place at that time. But Weinberger did institute several policies designed to curb predatory behavior by universities, enabling the Office of Education to cut funds or impose restrictions on schools that relied 60% or more on federal funds. Unfortunately, the Carter administration quickly scrapped these policies, leaving predatory behavior by federally subsidized universities relatively unchecked.

After contemplating the issue for years, the Clinton administration officially codified borrower defense rights in the Student Loan Reform Act of 1993. The initial program was enacted as a temporary measure in 1994, and states were given the authority to interpret the rather vague law as they saw fit. A panel consisting of various higher education stakeholders convened in 1995 to review the original phrasing of the policy and to propose more detailed guidance—but it concluded that no change was needed. It’s unclear exactly how the panel reached this conclusion, but some speculate that the ED preserved forgiveness in order to appease universities worried about their own liability. The panel never met again.

In recent years, the government has vacillated between different approaches to implementing the borrower defense program. The Obama administration revisited the borrower defense program and expanded what constituted “fraud” in 2016. In essence, the changes allowed students who felt that they hadn’t received a proper education from their university to file a claim with the Department of Education. The Trump administration rewrote the policy to take a stricter approach and avoid excessive debt forgiveness, but the Biden administration later reversed many of the Trump-era revisions.

Yet none of these administrations seriously considered how the government could prevent future predatory behavior by universities. Instead, taxpayers end up paying not only to subsidize the offending institutions but also to make restitution to their victims. Any borrower defense program that fails to address the underlying incentive structure for universities will necessarily be costly, ineffective, and counterproductive.

In order to fix these incentives, we should bring back Weinberger’s original policies: cut off federal funds to universities with high default rates and investigate universities that rely heavily on federal student loans.

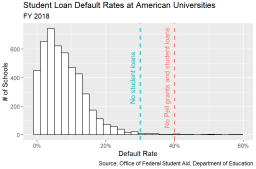

The ED already has a default rate cap in place. But the existing regulations set an incredibly low bar for universities seeking federal funding. Universities with a default rate of 30% or more lose access to Direct Loans, and those with a 40% or higher default rate also lose access to Pell grants (federal grants for low- and middle-income students). The figure below shows that just over 30 schools became ineligible for federal funds under these rules in 2018. But the reality is that most of these schools will not lose access to federal funds. In 2016, after successful appeals, only two out of the nine sanctioned schools actually lost their federal funding.

The student loan default rate cap is ridiculously high, especially when compared to other industries. In 2021, for instance, the consumer loan delinquency rate was under 2%. Even during the 2008 housing crisis, mortgage delinquency rates peaked at around 10%. If we are truly concerned about student loan debt, we should start by ensuring that taxpayers are not forced to subsidize schools where students have a greater than one in five chance of defaulting on their loan payments. In other words, both thresholds should be moved to 20% (at a minimum). This will reduce costs for taxpayers, both on the student aid side and the loan forgiveness side, and it will improve the average quality of schools that students can choose to attend.

[Related: “I Just Made My Last Student Loan Payment—Here’s How to Improve the System”]

Changing the incentive structures for universities will help to prevent the worst offenses. But even universities with low default rates are capable of committing fraud. A former dean for Temple University’s business school, for example, was convicted of fraud after he reported false information to the U.S. News & World Report in an effort to boost the institution’s ranking. And Columbia University math professor Michael Thaddeus recently uncovered evidence indicating that his own university similarly fudged their numbers.

In these instances, borrower defense could still serve its intended purpose to provide restitution to students who have been wronged by their universities. But we must narrow the definition of fraud to ensure that repayment goes only to the students who have actually suffered harm. The Obama and Biden administrations’ interpretation of fraud is too broad and leads to unnecessary expenses for taxpayers. The definition of fraud should mirror that of consumer protection laws, holding universities to the same standards as any other business.

Though more must be done to fix our broken higher education system, reforming the borrower defense program is a good place to start. Changing the incentive structure would raise the standards for university performance and discourage fraudulent activity across the board. Students who were wronged by their universities could still receive restitution—but without frequently diving into taxpayers’ pockets.

Image: Jp Valery, Public Domain

I disagree — the definition of fraud should be EXPANDED to that of the Consumer Protection laws. The so-called “Lemon” laws….