“… everything is queer today.”

– Alice

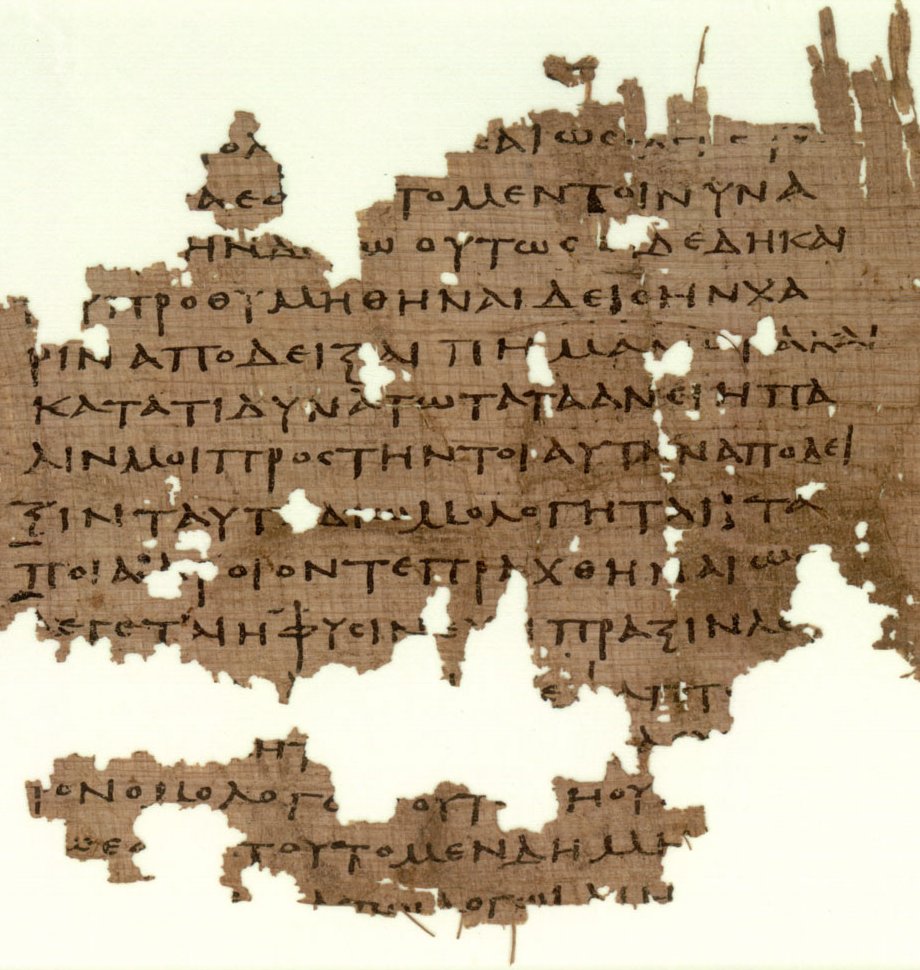

P. Oxy. LII 3679, 3rd century AD, with fragments of Plato’s Republic

Near the end of Plato’s Republic, a gap opens in the form of the famous Allegory of the Cave at the beginning of Book 7. It’s among the most metaphorical gestures in all of Plato’s work. As such it’s oddly foundational to the history of political thought. Plato encapsulates his message in the story of a man who escapes from a subterranean world. There, everything was fantasies, shadows, and distortions. And those still below? Ignoramuses subjected to a farce performed by others. In fact, the Allegory of the Cave telescopes a compound metaphor. There is an underground world, and within it there is a puppet show. One lie inhabits another. But is the underground as much of a lie as the show?

The least risky interpretation of this passage is that the act of leaving the cave represents the attainment of philosophical enlightenment. The knowledge imparted to us may be relative, but at least we know that the correct direction to take is up, toward the light of understanding in the sky. Light as it may seem, I propose we consider that the true message of the text lies hidden in the original direction of the marvels being projected on the wall of the cave.

A good philosopher, i.e., a philosopher who applies himself while reading Plato, will have learned to avoid the chimeras of the infernal regions. Upon leaving the cave, he experiences that Aufhebung of which the Germans speak, that is, he learns to see reality for what it is and not as it is contrived by others. By contrast, Socrates says explicitly that all political leaders, including kings, are among those fixated by the shadows on the wall at the bottom of the cave.

What if we read this part of The Republic in that direction, as do kings? The most tangible meaning of the Allegory of the Cave is revealing because it is not figurative. If we refuse to flee the cave, if instead we inspect it closely, we learn that the objective of the illusion is to validate a claim to the wall of the cave in the name of the republic, that is, in the name of a community we would call a society, state, or people. From this perspective, the moral is to understand that the lie projected onto the cave serves to claim the cave itself. Such knowledge interests princes.

It is no coincidence that a common feature of epic literature is a descent into the underworld (katabasis). This is precisely where the projection of the fantasies, national genealogies, moral systems, and other sources of wisdom at the base of the new social order is most urgently required. Epics reflect the power and, subsequently, the ideology of the ruling caste emanating from and focused on mines and mints. To control these is to control two great sources of wealth. Once coins are minted, they can be devalued to generate more revenue.

[More from Eric Clifford Graf: “How to Fix the Constitution of Soccer”]

The first modern novelist demonstrated how wondrous the transhistorical and multinational fantasy concocted to justify princely power can become (see DQ 2.23). That fantasy, of course, justifies the theft of the subsoil in the name of the Crown. In some cases, the fantasy has gone so far as to justify itself in the institution of chivalry. It can be very convincing, as seen in the Habsburg courts of the 16th century (see DQ 2.8, 2.17). An earlier example is King Henry II (r.1366–67, 1369–79) of the House of Trastámara, known as “the Knight,” and author of one of the greatest devaluations of the Castilian coinage (see DQ 2.60).

On the other side of the English Channel, the matter of who owns the subsoil is the most important exception in history. According to the law of capture, cuius est solum eius usque ad coelum et ad inferos, that is, “he who owns the soil owns it to heaven and to hell.” Already inviolable, property in the Anglo-Saxon imagination is also expansive and adventurous, we might even say novelistic. Without representation, there can be no taxation; and the owner of a plot of land also owns the entire sky above it and all the earth below it.

An individual who escapes Plato’s allegorical cave can consider himself unique. A remarkable feature of The Republic is the minority status of the successful intellectual. Furthermore, upon re-entering the cave to try to undeceive those who remain there, this same individual risks being considered insane. In truth, any individual who attains the status of madman runs the risk of being destroyed in the name of the group, that is, being sacrificed to affirm the unity of those who remain rigidly committed to the glory projected before them on the wall of the cave.

According to the Allegory of the Cave as it has been promulgated over many centuries, it would be a gesture of singular notoriety to argue that instead of leaving our darkness and discontent, we should penetrate it and further descant on the mine’s known deformity.

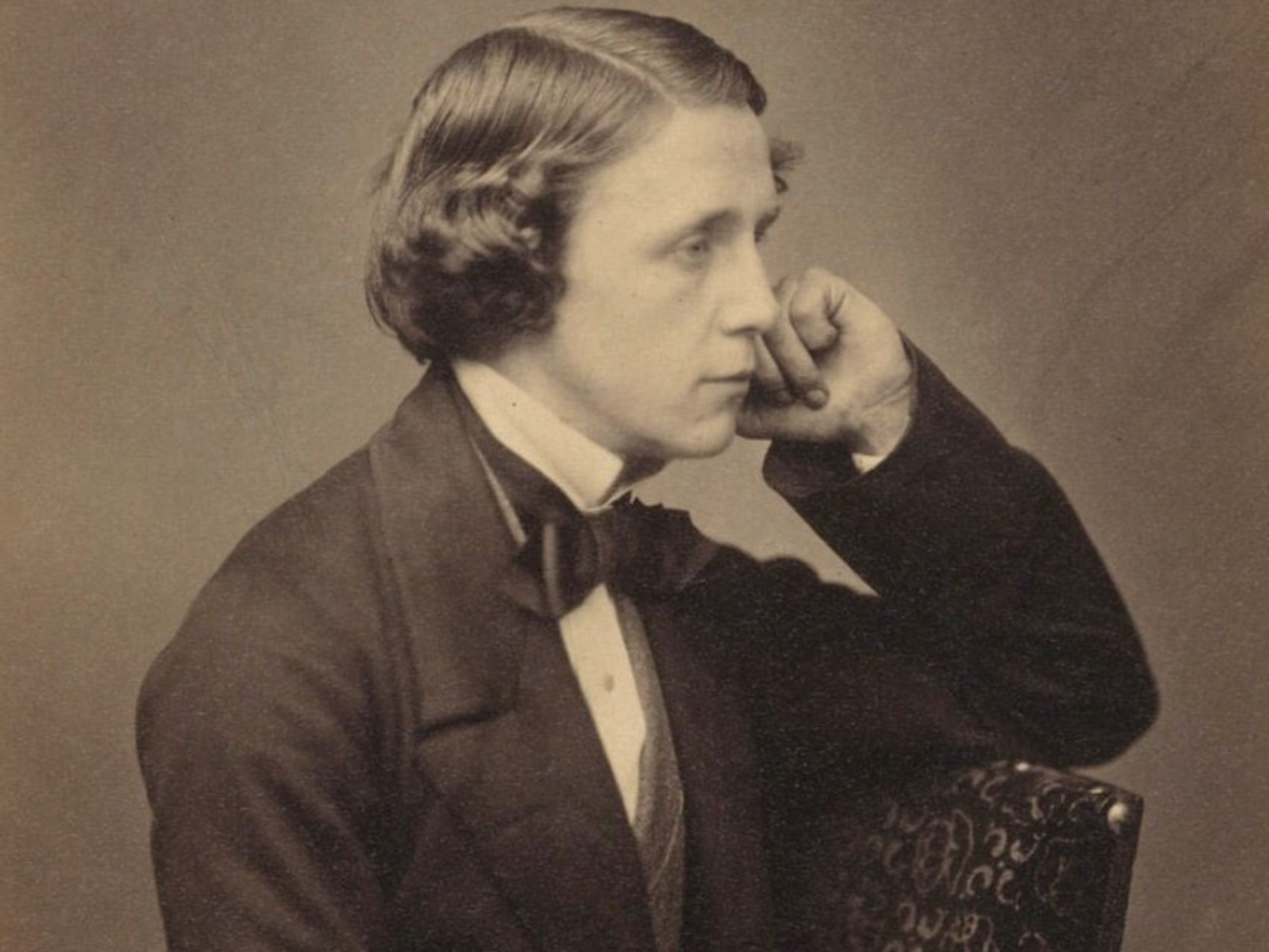

Lewis Carroll gestured at something along these lines in his novel Alice in Wonderland (1865).

Martin Gardner of Tulsa, Oklahoma—agreed by many to be most familiar with Carroll’s work—once observed that he was a raging Tory and a diehard supporter of the aristocracy. Apparently, he also groomed himself a gargantuan ego, being rather far from egalitarian in his outlook. This portrait echoes a passage penned by one William Tuckwell, who in his book Reminiscences of Oxford (1900) described his rival as “austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice’s landscape.”

[More from Eric Clifford Graf: “Donald Leslie Shaw, Happy Academic Warrior”]

After reading such disparaging remarks, we are forced to recall that—unlike our witty poet and mathematician from Cheshire—the aforementioned Tuckwell was a socialist who voluntarily monikered himself “the radical pastor” of the Anglican Church. He favored the nationalization of land. In sum, Tuckwell was a vulgar man of limited imagination, more like a hole in the ground than a citizen. This makes sense; he was from Woking in the mostly barren county of Surrey.

Here is a 180-degree inflection point between two Oxford schoolboys.

Over the years, those shocked by him have accused Carroll—whose real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson—of writing nonsense, taking drugs, and even being Jack the Ripper. If people think you’re capable of killing prostitutes in your spare time, and in so savage a manner, and while high on some form of opium, and all without getting caught, then I’d say you’re permitted to consider yourself an accomplished writer. Meanwhile, the saint for many will always be the socialist Tuckwell, who wanted to nationalize land and redistribute wealth. I wager Dodgson knew right well that such a crude pastor deserved not only to be scorned as an utterly dishonorable person, but beheaded as an inadequate enemy of the Queen of Hearts.

A political economy that affirms religious freedom even for the king has at least stood for something. One that asserts the collectivization of property, contra the long, glorious tradition of English common law, seeks only to satisfy the masses. In America, the Constitution forbids titles of nobility, but I swear right here and now, before God Almighty and the nation, that the instant they come for my land I will blossom into a fanatical defender of the most recalcitrant and mystical aristocracy you can imagine. I’ll convert to Judaism. I’ll dress and march through other people’s neighborhoods like a warrior priest from Mesoamerica or a Russian Cossack. Realism for the people? Boring and dangerous. Under no circumstances.

Dodgson died on 14 January 1898, the year of the last major conflict between Catholics and Protestants. I don’t know if he’d have endorsed the struggle against Spain as did our realist novelist Mark Twain or the insufferably populist poet Walt Whitman. I’m left to assert that Lewis Carroll was a writer with a tremendous imagination. The painter Salvador Dalí, another creator of worlds in a time of cholera, declared himself “a monarchist in the metaphysical sense.” Given our latest and most insane outbreak of identitarian collectivism in the West, we’re still free to imagine that Carroll would have us roundly reject thinking like “democrats in the material sense.” You see, equality, too, must have its limits. It may be true that you cannot get into the garden if you are bigger than the door or smaller than the key, but for that to happen caterpillars must be allowed to speak. Similarly, claiming land in the name of the state, especially in England, provides the material grounds for a most unimaginative way of thinking.