If you listened to the first day of oral arguments in the twin racial preference cases before the Supreme Court, you might have wondered whether the participants were AWI—Arguing While Intoxicated. Surely, they must have known that ‘diversity’ is an illusion. Humans have far preferred tribal, sectarian, kin, national, ethnic, linguistic, and racial categories; or, when forced to compete in some way, humans have opted for metrics of strength, endurance, power, and even the capacity to spell words (the spelling bee). ‘Diversity’ did not factor into how we organized social units until notions of racial balancing became a fashionable workaround for quotas.

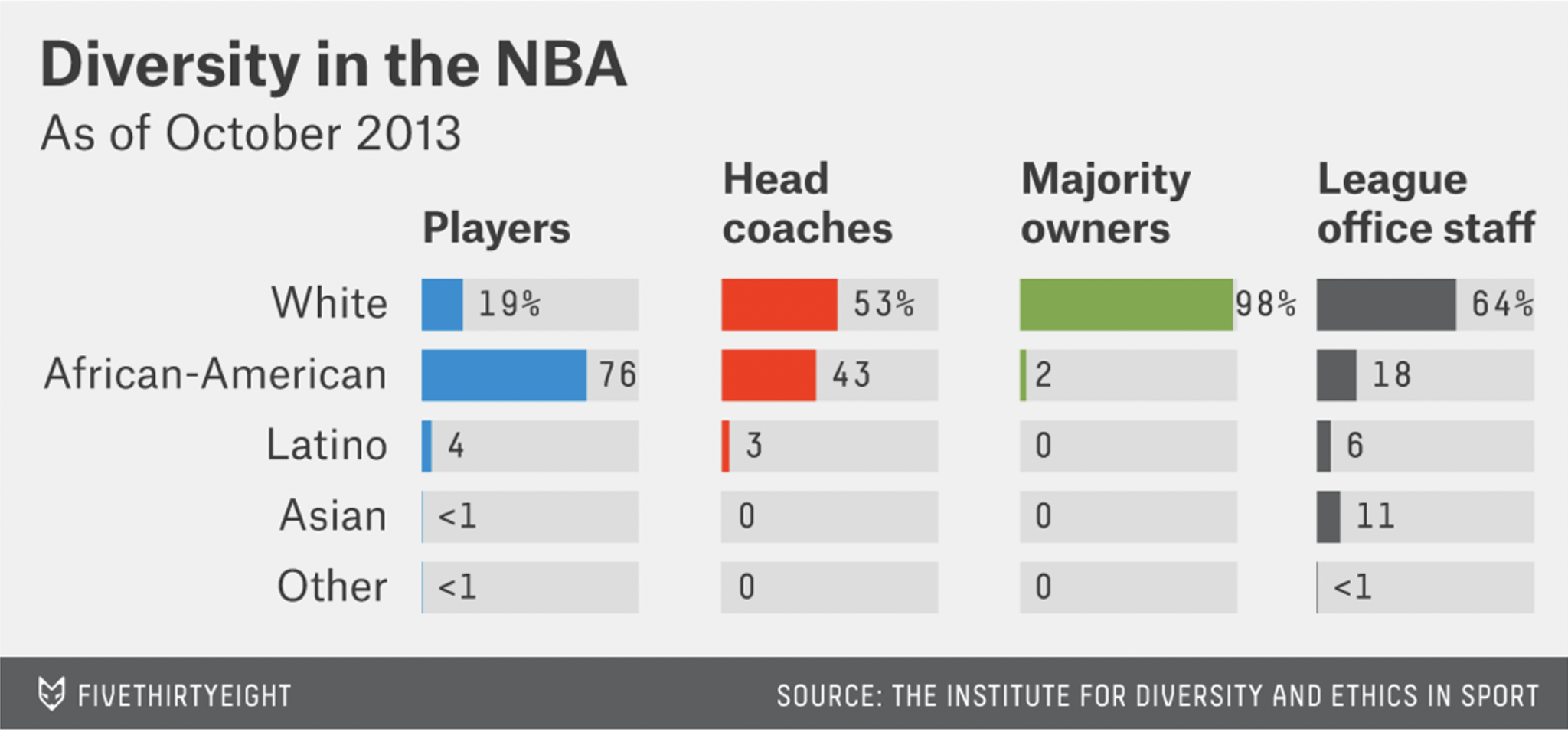

I imagine that a significant number of SCOTUS listeners, and those who follow up on news commentary, will think of the NBA. NBA players are predominantly African American; there is a significant white minority and a small percentage of Asian and other. White and African-American proportions switch in league office and head coaching positions, with whites dominating as CEO/President. For players, what matters most is merit—the ability to play the game. Looking at player statistics, Brookings writers Steven Foy and Rashawn Ray observed that “a racial breakdown shows that the NBA is the most racially diverse major U.S. sport.”

But that doesn’t make sense, does it?

According to the U.S. Census, blacks (or black alone to exclude multiracial data) in America are 12.4% of the total U.S. population (2020). Whites (or white alone) are 61.6%. That’s about the reverse of the NBA player racial data. Even if one looked at college-aged athletes by race, we find a similar comparison: white (67.7%), Black or African American (9.2%). So, a “diverse” NBA would have whites at about 60%+ with blacks at about 10%+. However, commentators often say that “diversity” means mostly black or mostly POC (people of color), as opposed to that which represents the racial makeup of the society at large.

Source: FiveThirtyEight

Those who pay attention to real-world metrics are aggravated when diversity and inclusion are substituted for merit. Walter E. Williams pointedly expressed his dismay this way:

What explains the fact that over 80% of professional basketball players are black, as are about 70% of professional football players? Only an idiot would chalk it up to diversity and inclusion. Instead, it is excellence that explains the disproportionate numbers.

Jewish Americans, who are just 3% of our population, win over 35% of the Nobel prizes in science that are awarded to Americans. Again, it is excellence that explains the disproportionality, not diversity and inclusion.

As my stepfather often told me, “To do well in this world, you have to come early and stay late.”

In university admissions, to “come early and stay late” would refer to the poor education that many, especially blacks and Hispanics, receive at the K–12 level, thereby requiring race-conscious admissions to fix the pre-college inadequacy. The last Supreme Court decision in this arena, Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), anticipated that such race-consciousness would no longer be required twenty-five years hence. Grutter allowed race to be one factor among many. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor noted that the decision “does not prohibit the law school’s narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body.”

[Related: “Enforcing the Coming Affirmative Action Bans: A Modest Proposal”]

The Supreme Court’s current discussion stumbled over whether twenty-five years is enough to allow for the continued perversity of race-consciousness. Why perverse? Clearly, the American legal structure speaks out loudly against it, and the universities have been granted a narrow reprieve.

The discussion also stumbled over whether the universities could ever arrive at an adequate level of racial “diversity.” Could the universities fix problems that make up the tectonics of wider society? If not, then the twenty-five-year goalpost is imaginary.

After Race-conscious Admissions: Alternatives

The most obvious alternative is to eliminate race-consciousness in the university admissions process. The Supreme Court opinion would note the importance of improving K–12 education for all students with commitment from teachers, administrators, students, and parents. The opinion might also note that public charter schools have been succeeding in this endeavor. Excuses have had their day.

There are three ways to eliminate race-consciousness, two of which are likely being discussed by the Court. First, the Court can simply declare that the time has expired on race-conscious admissions and that it can no longer be tolerated. Justice Thomas expressed this view in his Grutter concurrence in 2003. He quoted Justice Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” For Justice Thomas, the time to put the 14th Amendment into effect is now.

Alternatively, the Court could substitute the legacy of slavery for the current race-consciousness. There is a significant difference. And it is noted in the United States Constitution.

The 13th Amendment, section 1, states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude . . . shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Universities that benefitted from slavery or continued to discriminate against former slaves after the Civil War could use the legacy of slavery as its own restitution for those descendants. That would be a narrow tailoring of factors used in a holistic admissions process.

The 14th and 15th Amendments treat race as distinct from slavery. The 14th Amendment, section 1, provides equal protection to all: “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The 15th Amendment, section 1, explicitly differentiates “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Thus, SFFA v. Harvard and SFFA v. University of North Carolina, to the extent that they are both entangled with government or government funding, could be tasked to end the use of race-consciousness as a violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments while, at the same time, giving permission for colleges and universities to use the legacy of slavery as a factor in their holistic admissions processes.

A less obvious and more radical alternative is a randomized selection process. The applicant pool could be envisioned like a military draft, where all males and females would receive a priority number once they turn seventeen or eighteen. Those who elect not to go to college would waive their number, which would then move up the next applicants in the pool. Or the applicant pool could be narrowed to some aspirational criterion (regional designation, technical versus academic track, military versus civilian, and the like). Perhaps all universities would receive the same tuition—sort of like Medicare reimbursements. Whatever the final process, it would obviate the need for court supervision inasmuch as race-consciousness would not be included.

Jonathan Turley analyzed a growing interest in randomized admissions, quickly rejecting it as leading to a poorly qualified student body.

It would also destroy any value for the students to work to achieve greater achievement in math, science, and other subjects. [Students] would be free to spend, [quoting an advocate of a random approach, Cathy O’Neil Bloomberg] their time “smoking pot and getting laid in between reading Dostoyevsky and writing bad poetry.” The new model for admissions would range from Hunter Thompson to Hunter Biden.

The push for blind or random admissions is the ultimate sign of the decadence of society. What O’Neil is describing is a system designed for the intellectual dilettante. Of course, countries like China are moving to dominate the world economy with kids who are not focusing on good sex and bad poetry. Higher education has long been based on intellectual achievement and discovery. Admission to higher ranked schools has been a key motivating factor for millions of students, including the children of many first generation Americans. Their achievement has translated into national advancement in science and the economy. It has served to bring greater opportunities and growth for all Americans.

I hesitate to discount a randomized social unit, whether that be a university freshman class or a workplace. While there are social units that would cause us to laugh if they were selected on a random basis from the general population, such as a professional basketball team or a surgical operating team, other social units have more flexible entry conditions—think bootcamp from a national draft or volunteers manning a soup line.

[Related: “Race Consciousness Hangs by a Thread”]

Chengwei Liu asks us to consider an openminded approach that could be tailored to the workplace.

[A]n organisation may have all the intentions of hiring a diverse workforce, they tend to rely too heavily on meritocracy – hiring the ‘best’.

[O]rganisations often neglect cognitive diversity, focusing solely on identity diversity. For example, hiring people from different places or different backgrounds does not necessarily mean they think differently, which is essential to generating a diversity bonus. . .

Random selection cannot beat a decision based on good reasoning. However, there is not always a justifiable reason for hiring one person over another. . . .

Random selection can address biases in the recruitment process, such as meritocracy bias, nepotism, or stereotyping. Meritocracy is often overlooked as a bias but is actually responsible for the paradox of merit.

Workplaces can think they’re doing the right thing by hiring the best, but this can lead to less diversity.

In later stages of selection, to capture the diversity bonus, organisations should dismiss the best candidates as they are unlikely to provide additional cognitive diversity, and instead use random selection among the rest.

A randomized approach has value as a thought experiment. It may yield positive (Liu) or negative (Turley/O’Neil Bloomberg) results. Since it is unlikely that higher education will implement randomized admissions, the actual choice is to either continue postponing the deadline of Grutter’s race-consciousness or to follow the path out of race-consciousness into necessary educational reform.

Image: Adobe Stock

A randomized approach may have value “as a thought experiment,” but as a realistic approach it should never be accepted. Imagine a college populated by all “C” students, simply because they won the college entrance lottery. Then imagine all those “C” students being pushed through graduate school, medical school or law school. Meanwhile, the “A” and “B” students will fill the ranks of waitresses, garbage collectors and street cleaners. What a society that would create! The randomized approach is just a work-around to avoid the “M” word. But merit will win in the end because no one wants to fly in a plane being piloted by a “D” student.