The nation’s 250 Anniversary is only 29 months away. The National Association of Scholars is commemorating the events that led up to the Second Continental Congress officially adopting the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. This is the forth installment of the series. Find the fourth installment here.

Intolerable is a strong word. We can and should tolerate a great many things, and tolerance is usually rightly called a virtue. But sometimes, it is not, and sometimes, the word intolerable is justified.

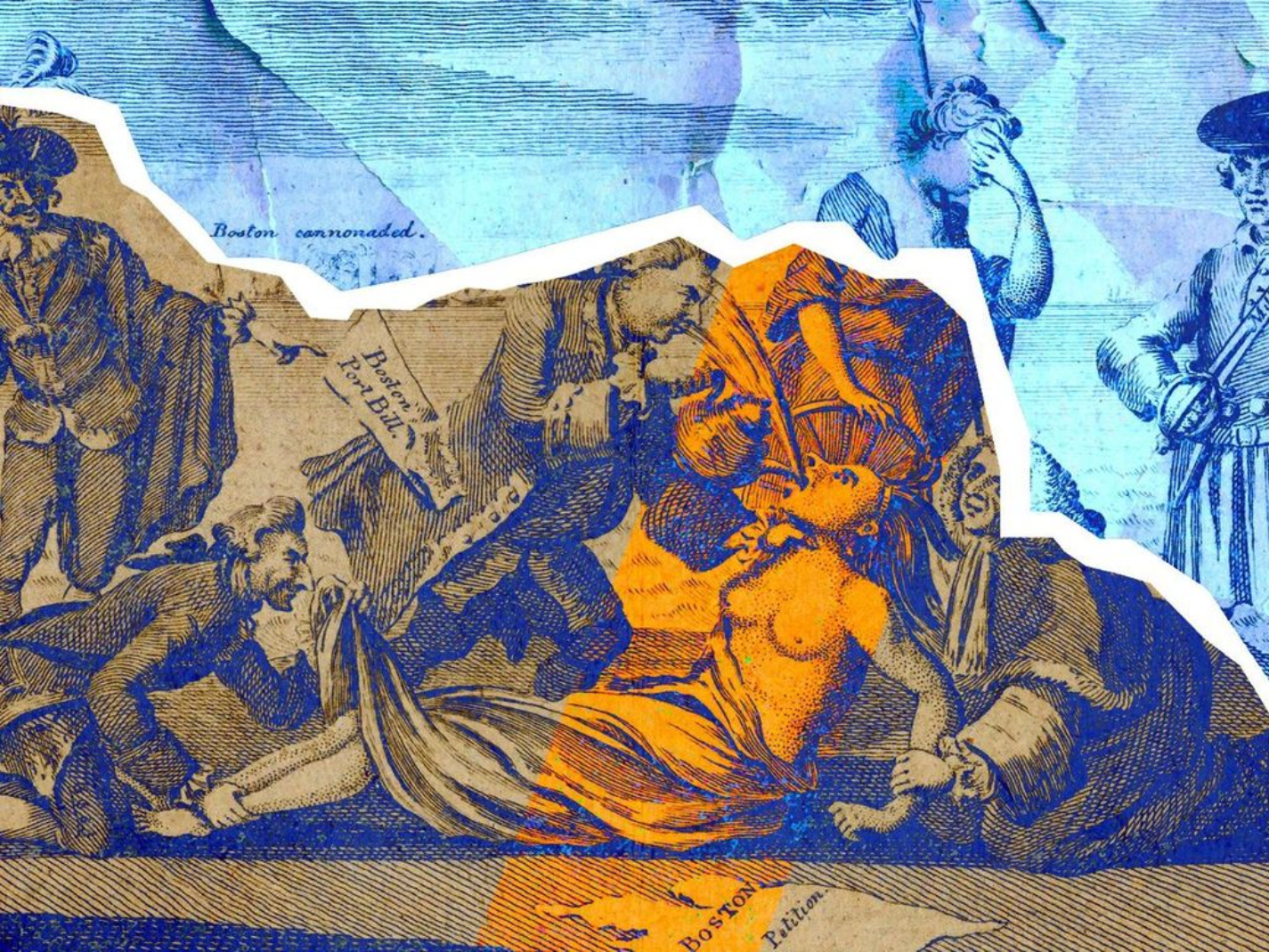

The British Parliament was not pleased when news of the Boston Tea Party arrived in London early in 1774. The British government immediately set about to restore British law and order in Massachusetts. Parliament passed the first of the four Intolerable Acts on March 31, 1774; by June 2 of that year, all four had received King George’s assent.

The Boston Port Act authorized the Royal Navy to shut down all commerce in Boston Harbor until the British government determined that Massachusetts was properly obedient and law-abiding.

The Massachusetts Government Act virtually ended representative self-government in Massachusetts and replaced it with royal control.

The Administration of Justice Act allowed the government to transfer trials of accused royal officials from Massachusetts to anywhere else in the British Empire.

The Quartering Act gave all governors in British North America the right to billet troops in privately owned buildings.

At once, Britain attacked colonial self-government, colonial justice, colonial commerce, and colonial rights to private property. It replaced them with the full despotic panoply of arbitrary government.

The Boston Port Act came first, and it hit hardest. British navy ships would shut Boston Harbor until Bostonians recompensed the East India Company for their lost tea. Nor would the harbor reopen until “it shall be made to appear to his Majesty, in his Privy Council, that peace and obedience to the laws shall be so far restored in the said town of Boston, that the trade of Great Britain may be safely carried on there, and his Majesty’s customs duly collected.” Great powers seizing the custom houses of unruly small republics behave in this fashion. This was more an act of war than a law.

Can you be part of a country that has declared war on you?

You can understand why the colonists thought the Boston Port Act was intolerable, even before its companions came along. You can understand why British subjects from New Hampshire to Georgia were as outraged as their fellow Bostonians. Every American realized that the suffering Great Britain inflicted on Massachusetts endangered his own rights of self-government and liberty.

The British parliament’s opposition also thought the Acts were woefully misguided. Edmund Burke opposed them because they violated what he took to be the constitution of the British empire—a sort of federalism avant la lettre: “She [the British parliament] is never to intrude into the place of the others [colonial legislatures], whilst they are equal to the common ends of their institution.” Britain’s intolerable violations of individual American liberty flowed from its abrogation of the imperial federalist constitution to violate American self-government.

Everything old is new again. A great deal of what is intolerable about the American federal government nowadays likewise flows from its violation of its federal compact with the states.

Education bureaucrats abuse their power over federal grants and loans to seize control of public universities and K-12 schools from the states. They violate the federal compact every day.

Public health bureaucrats ran roughshod over state liberty during the COVID pandemic as a necessary means to violate local and individual liberty. What they did once, they’re ready to do again.

Our all-too-imperial federal government innovates on its British predecessor by deliberately failing to enforce the border against entry by illegal aliens—shirking its constitutional duty to “protect each of them [the states] against Invasion”—and compounds its failure by preventing the states from taking their own measures to guard the border. It’s like a lifeguard who not only refuses to save a drowning man but also arrests any bystander who jumps in the water to do his job for him.

Our swollen federal government acts by regulation more than by statute, so it cannot even be restrained by our legislature. If it finally sparks rebellion, doubtless it will be through Intolerable Implementations of Bureaucratic Boilerplate.

But the rebellion would be as fierce. And a state may prove to be our palladium of liberty, as a colony was then. If Texas rebelled against Washington to preserve its border against foreign invaders, and against federal sabotage of that border, it would be the Massachusetts of our day.

If. We are finding out just how intolerably our government can act before the people rebel.

Miguel Cardona — U.S. Secretary of Education — US Department of Education — Flickr

Anthony Fauci — Former Chief Medical Advisor to the President of the United States — The White House — Flickr

Alejandro Mayorkas — U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security — Photo by Zachary Hupp — Department of Homeland Security

Intolerable Acts

—After Dylan Thomas

Do not surrender when you are attacked.

Free men should burn and rave against base law;

Rage, rage against intolerable acts.

Though tyrants say authority’s a fact

We should regard as worthy of our awe

Do not surrender when you are attacked.

Reformers say we should proceed with tact—

But how can we endure when flesh is raw?

Rage, rage against intolerable acts.

What if our sovereign breaks the old compact?

What if he crams injustice down our craw?

Do not surrender when you are attacked.

If he should strike us, will we not react?

We have our swords, which we know how to draw.

Rage, rage against intolerable acts.

Our liberty will be the artifact

We’ll forge when we have been declared outlaw.

Do not surrender when you are attacked:

Rage, rage against intolerable acts.

Art by Beck & Stone

“The Boston Port Act authorized the Royal Navy to shut down all commerce in Boston Harbor…”

The text of the act: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Boston_Port_Act

The act actually did a bit more than that — they closed the entire bay, from Nahant Point to Alderton Point, all of the harbor islands, and three nautical miles (a league) beyond all of this. See: https://www.tide-forecast.com/tidelocationmaps/Boston-Light-Boston-Harbor-Massachusetts.10.gif — it essentially would be Nahant to Hull, and the Nahant causeway to Lynn (it was a half-tide sand bar then) is a little over a nautical mile long so it gives an idea of the extent of exclusion zone.

For starters, this was a violation of International Law — any vessel from a non-belligerent state had to be provided access to a “harbor of refuge” — a place to seek shelter from storms and the ability to repair storm damage to the ship. Masts got broken, sails ripped, etc., and if someone limped into your harbor, you had to let them do this.

And then there were the exceptions, anything sold to the British and “any fuel or victual brought coastways from any part of the Continent of America” as long as it was going to be consumed in Boston.

This would have created a major problem that I have never seen addressed — *all* of the fuel (firewood) was sailed down from Maine, and it then was either sold to the British for hard currency or bartered for grain, which does not grow on the foggy Maine coast. Hence even if the grain could be brought into Boston, it couldn’t be exported and hence only certain persons could heat their houses the following winter as there was no grain to trade for firewood.

Boston has a natural harbor, one of the best in the world, and its why Boston was far larger than New York City until the introduction of steam tugs which made it easy for sailing ships to go upriver. It’s why Boston replaced Salem, it was easier to get in and out of in the days of sail. And then goods would be brought in from overseas by ships (dishes used to be packed in barrels and actually arrived unbroken), offloaded, and then reloaded into coastal schooners who would either resell them elsewhere or take them home.

It really was an act of war.